Introduction

Unlike other guided interview systems, in which the interview developer maps out a decision tree or flowchart to indicate which questions should be asked and in which order, docassemble figures out what questions to ask and when to ask them based on rules that you specify. You specify these rules using YAML blocks.

Simple interviews: all blocks mandatory

The simplest type of rule you can specify is marking a block as

mandatory.

mandatory: True

question: |

Welcome to the interview!

continue button field: intro

---

mandatory: True

question: |

What is your favorite fruit?

fields:

- Fruit: favorite_fruit

---

mandatory: True

question: |

What is your favorite vegetable?

fields:

- Vegetable: favorite_vegetable

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Here is your document.

attachment:

content: |

Your favorite fruit is ${ favorite_fruit }.

% if favorite_fruit == 'apple':

You will never need to see a doctor.

% endif

Your favorite vegetable is ${ favorite_vegetable }.When docassemble runs an interview, it looks at the YAML and

tries to run each block that is marked as “mandatory.” It will run

them in the order in which they appear in the YAML. In this

example, first the “Welcome to the interview!” question is asked.

When the user clicks the “Continue” button, docassemble moves on

to the second mandatory block, which asks “What is your favorite

fruit?” When that question is answered, docassemble asks “What is

your favorite vegetable?” When that question is answered

docassemble moves on to the final question, “Here is your

document,” which lets the user download a document. This is a very

simple interview because there is no branching logic.

Suppose that instead of asking for the user’s favorite vegetable, you

wanted to ask for the user’s favorite apple, but only if the user said

that their favorite fruit is “apple.” In the previous interview, we

set mandatory to True every time, but we can actually set

mandatory to a Python expression that evaluates to a true or

false value. For example:

mandatory: True

question: |

Welcome to the interview!

continue button field: intro

---

mandatory: True

question: |

What is your favorite fruit?

fields:

- Fruit: favorite_fruit

---

mandatory: favorite_fruit == 'apple'

question: |

What is your favorite type of apple?

fields:

- Type of apple: favorite_apple

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Here is your document.

attachment:

content: |

Your favorite fruit is ${ favorite_fruit }.

% if favorite_fruit == 'apple':

Your favorite type of apple is ${ favorite_apple }.

% endifHere, the “What is your favorite type of fruit” question is only

“mandatory” if the user says that apple is their favorite type of

fruit. Thus, if the favorite_fruit variable is 'banana', then

docassemble will skip over the “What is your favorite type of

apple?” question and proceed directly to the “Here is your document”

question.

By setting the mandatory directive to a Python expression that

uses variables defined in previous question blocks, you can write

complex interviews that branch in a lot of different directions

depending on the interview answers.

However, in a complex interview with a number of nested branches of

logic, the Python expressions you will need to write to indicate

whether a question should be asked could be very long and

complicated. In the next section, we will discuss another way of

implementing branching logic that avoids this complication.

Complex interviews: dependency satisfaction

As explained in the previous section, when docassemble runs your

interview, it goes through your YAML from beginning to end and

attempts to run each block that is marked as mandatory. Marking a

question as “mandatory” is one way to tell docassemble you

want a question to be displayed.

docassemble can also do “dependency satisfaction.” For example, you can write an interview like this:

mandatory: True

question: |

Your favorite fruit is ${ favorite_fruit }.

subquestion: |

% if favorite_fruit == 'grapes':

Your favorite vineyard is ${ favorite_vineyard }.

% endif

---

question: |

Which vineyard do you think produces the best grapes?

fields:

- Vineyard: favorite_vineyard

---

question: |

What is your favorite fruit?

fields:

- Fruit: favorite_fruitIn this interview, there is a mandatory question and then two

questions that do not have a mandatory directive on them. If you

run the interview, the first question asked is “What is your favorite

fruit?” How did docassemble know it needed to ask that question,

even though it was not marked as mandatory? What happened was

that docassemble tried to display the “Your favorite fruit is …”

question, but in the process of doing so, it encountered an undefined

variable favorite_fruit. So then it looked for a block that defines

the ‘favorite_fruit’ variable, and it found one, so it asked the “What

is your favorite fruit?” question.

If the user types grapes in answer to that question, the interview

asks a follow-up question, “Which vineyard do you think produces the

best grapes?” and then proceeds to the final screen, which says “Your

favorite fruit is grapes.” However, if the user says their favorite

fruit is “apples,” the interview will skip the “Which vineyard do you

think produces the best grapes?” question and will proceed directly to

the final screen, which says “Your favorite fruit is apples.” Thus,

with a single mandatory question, the interview does branching

logic.

The branching logic is a by-product of the attempt to display the

single mandatory question. If you were to change the text of the

question and remove the reference to favorite_vineyard, the “Which

vineyard do you think produces the best grapes?” question would never

be asked. Or, if you were to change the question text to Your

favorite fruit is ${ favorite_fruit } and your favorite vegetable is

${ favorite_vegetable }. then the order of questions would change,

and the question that defines favorite_vegetable question would be

asked right after the favorite_fruit question. When dependency

satisfaction is used to ask questions, the order of questions is

determined by which variables docassemble sees first.

Note that the order in which non-mandatory questions appear in the

YAML does not affect the order in which questions are asked. Each

block in your YAML is a just a “rule,” and you can specify as

many “rules” in your YAML as you want, in any order.

For example, the following block is a rule that indicates whether the user is eligible for a benefit.

code: |

if user.age_in_years() >= 60 or user.is_disabled:

user.eligible = True

else:

user.eligible = FalseThe rule says that the user is eligible if they are 60 or older, or if they are disabled, otherwise the user is not eligible.

Rules in docassemble are instructions for how to define a

particular variable. The code block above is a rule for how to

define user.eligible. question blocks are also rules. Here is

a rule that specifies how to define user.is_disabled:

question: Are you disabled?

yesno: user.is_disabledThis says that the rule for defining user.disabled is to ask the

user a yes/no question.

It is possible to specify rules in fairly complex ways, as we will see later; you can write multiple blocks that define the same variable, so you can have alternative rules for different circumstances, or you can have a general rule that is overridden by a more specific rule in certain circumstances. You can write generic rules that apply to a variety of different variables.

When docassemble runs your interview, it will try to run your

mandatory blocks, in the order in which the blocks appear in your

YAML. In the course of trying to run a block, docassemble might

encounter a variable that hasn’t been defined yet. When this happens,

docassemble will evaluate the “rules” you have defined, and it

will run code blocks, question blocks, or other types of

blocks in order to try to obtain a definition of the undefined

variable.

In the course of trying to define a variable, docassemble might

encounter yet another undefined variable, in which case it will try to

obtain a definition of that variable, and in the course of trying to

define that variable, it may encounter yet another undefined variable.

A rule that defines a variable may “depend on” the values of other

variables. docassemble’s logic engine will perform “dependency

satisfaction” by automatically figuring out what variable definitions

are necessary and running the appropriate code blocks or showing

the appropriate question screens to the user.

This allows you, as the interview author, to specify rules and use variables in your interview or in your documents as you see fit, while docassemble does all the thinking about which questions need to be asked and in what order to ask them.

docassemble automatically refrains from asking unnecessary questions. For example, consider this example:

code: |

if user.age_in_years() >= 60 or user.is_disabled:

user.eligible = True

else:

user.eligible = FalseIf the user is 60 or older, there is no need to ask the user if they are disabled. It would waste the user’s time to ask that question. docassemble infers this from the rule. Thus “how to conduct the interview” and “what the legal rules are” are effectively the same thing, and can be specified in a single location.

Manually specifying the order of questions

Sometimes, you might not want the order of questions in the interview

to be implicitly determined by the way docassemble processes

rules; you might want to explicitly specify the order of questions.

You can do this using a code block.

mandatory: True

code: |

if favorite_fruit == 'grapes':

favorite_vineyard

favorite_vegetable

final_screen

---

event: final_screen

question: |

Your favorite fruit is ${ favorite_fruit }.

subquestion: |

Your favorite vegetable is ${ favorite_vegetable }.

% if favorite_fruit == 'grapes':

Your favorite vineyard is ${ favorite_vineyard }.

% endif

---

question: |

Which vineyard do you think produces the best grapes?

fields:

- Vineyard: favorite_vineyard

---

question: |

What is your favorite fruit?

fields:

- Fruit: favorite_fruit

---

question: |

What is your favorite vegetable?

fields:

- Vegetable: favorite_vegetableIn this interview, the mandatory code block drives the interview

using dependency satisfaction, but in an explicit order. This block

contains a few lines of Python code. The first variable encountered

is favorite_fruit, which means that the favorite_fruit question

will be asked. If favorite_fruit is 'grapes', then

favorite_vineyard is evaluated, which means that favorite_vineyard

will be asked. Then favorite_vegetable is asked, and then

final_screen is sought. Because final_screen is a special screen,

and the event directive is set to final_screen, the variable

final_screen will actually not be defined; the screen is a dead-end

screen with no fields and no “Continue” button.

If the mandatory code block was not present, and instead the

final_screen block was marked mandatory, then the questions

would have been asked in a different order: first favorite_fruit,

then favorite_vegetable, and then favorite_vineyard (if the

favorite_fruit was 'grapes'). We were able to instruct

docassemble to ask for favorite_vineyard immediately after

favorite_fruit by specifying different interview logic in the

code block.

This mandatory code block serves as an “outline” for the

interview. Instead of ordering blocks in your YAML, you can simply

order lines in your mandatory code block. The code block lets

you see the order of your interview at a glance, without having to

page through a long interview. The indentation of text under if

statements makes clear where there is a “branch” in the logic.

If you are familiar with Python, you might think that the mandatory

code block is weird, because simply putting the name of a variable

by itself on a line doesn’t do anything; it’s not something that

programmers normally do. However, it does something in

docassemble, because if the variable is undefined, a Python

exception will be “raised,” and the raising of that exception will

tell docassemble that a definition of that variable needs to be

obtained. docassemble’s dependency satisfaction system operates

through the triggering of undefined variable exceptions.

So far, we have discussed three different techniques for specifying interview logic in docassemble:

- A series of

questionblocks withmandatorydirectives on them; - Allowing

questionblocks to be asked implicitly as a result of dependency satisfaction; and - Writing a

codeblock marked asmandatorycontaining an explicit outline of the variables that need to be gathered and the conditions under which each variable definition should be sought.

These three techniques are not mutually exclusive; you can use them

together. For example, you might have a mandatory question block

followed by a mandatory code block, followed by a mandatory

question block.

mandatory: True

question: |

Welcome!

continue button field: intro_screen

---

mandatory: True

code: |

intro_screen

user.name.first

final_screen

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Your preferences.

subquestion: |

Your favorite fruit is ${ favorite_fruit }.

Your favorite vegetable is ${ favorite_vegetable }.

% if favorite_vegetable == 'turnip' and user.grows_own_turnips:

I grow turnips too!

% endifOr you could have a mandatory code block that only partially

specifies the order of questions, and allows many questions to be

asked explicitly. For example:

mandatory: True

code: |

intro_screen

user.name.first

final_screen

---

question: |

Welcome!

continue button field: intro_screen

---

event: final_screen

question: |

Your preferences.

subquestion: |

Your favorite fruit is ${ favorite_fruit }.

Your favorite vegetable is ${ favorite_vegetable }.

% if favorite_vegetable == 'turnip' and user.grows_own_turnips:

I grow turnips too!

% endifHere, the mandatory code block ensures that intro_screen and

user.name.first are asked up front, but then uses dependency

satisfaction to trigger the asking of favorite_fruit and

favorite_vegetable, as well as the display of the final_screen.

Writing law as code to drive the interview

docassemble’s “rules”-based logic system is particularly well-suited for legal applications. You can write legal logic in Python code, and docassemble will figure out how to ask the necessary questions to arrive at a legal judgment.

For example, suppose your interview needs to determine whether the user has legal standing as a grandparent to seek custody of a child. The relevant statute states that a grandparent can seek custody under the following circumstance:

(3) A grandparent of the child who is not in loco parentis to the child:

(i) whose relationship with the child began either with the consent

of a parent of the child or under a court order;

(ii) who assumes or is willing to assume responsibility for the

child; and

(iii) when one of the following conditions is met:

(A) the child has been determined to be a dependent child under

42 Pa.C.S. Ch. 63 (relating to juvenile matters);

(B) the child is substantially at risk due to parental abuse,

neglect, drug or alcohol abuse or incapacity; or

(C) the child has, for a period of at least 12 consecutive

months, resided with the grandparent, excluding brief

temporary absences of the child from the home, and is

removed from the home by the parents, in which case the

action must be filed within six months after the removal of

the child from the home.The interview developer can rewrite this statute in Python, converting each legal concept into a variable.

comment: 23 Pa. C.S.A. 5324(3)

code: |

if relationship == 'Grandparent' \

and (relationship_began_with_consent \

or relationship_began_with_court_order) \

and willing_to_assume_responsibility \

and (child_is_dependent \

or child_is_at_risk \

or cared_for_child_for_a_year):

has_grandparent_standing = True

else:

has_grandparent_standing = FalseNote: if you are wondering why there are \ marks at the end of some

of the lines, this is Python syntax for formatting source code and

avoiding writing a very long line of code. If the \ was not

present, there would be a syntax error, because Python would interpret

the newline to mean that you were done specifying a condition, and it

would think you forgot to write a : to indicate the end of the

condition. The \ basically means “ignore the following newline and

pretend this is all one long line.”

The values of a variable like relationship_began_with_consent could

be determined by asking the user a question.

question: |

At some point, did one of the child's parents agree to let you care

for the child?

yesno: relationship_began_with_consentOther variables, like cared_for_child_for_a_year, might be too

complex to reduce to a single question. In that case, rather than

using a question as the “rule” for what the variable means, you

can use a code block instead, and you can break the legal concept

down into smaller pieces.

code: |

if (not child_lives_with_client) \

and child_used_to_live_with_client \

and child_taken_from_client_by_parent \

and child_taken_within_last_six_months \

and child_moved_in_at_least_12_months_before \

and child_lived_with_client_continuously:

cared_for_child_for_a_year = True

else:

cared_for_child_for_a_year = FalseThe rules for what these variables mean can in turn be specified as

question or code blocks:

question: |

Does the child currently live with you?

yesno: child_lives_with_client

---

code: |

if as_datetime(date_child_taken_away) >= date_as_of_six_months_ago:

child_taken_within_last_six_months = True

else:

child_taken_within_last_six_months = FalseGiven YAML rules like this, docassemble can automatically

conduct a parsimonious interview; that is, it will not ask any

unnecessary questions. For example, if

willing_to_assume_responsibility is False, it will not ask

child_is_dependent. The only thing you need to do to trigger this

process is to set up a mandatory block that requires a definition

of has_grandparent_standing.

mandatory: True

code: |

if relationship == 'Grandparent' and not has_grandparent_standing:

grandparent_not_eligible

final_screen

---

event: grandparent_not_eligible

question: |

Sorry, you do not have standing as a grandparent to seek custody

under Pennsylvania law.Many beginners find this style of rule-based logic specificiation to be confusing; they would rather specify exactly which questions are asked, and exactly what happens as a result of the answer to each question. However, when there are numerous legal rules and the interaction of the legal rules leads to a large number of possible scenarios, planning in advance the interview process for each one of these scenarios is time-consuming, and the work involved is mechanical rather than substantive. If you are going to offer users the ability to spot-edit any of their prior answers to questions in the middle of the interview, you will need to think about exactly which follow-up processes are necessary when the user makes such changes.

The “declarative” style of logic is very useful in these circumstances. All you need to do is the work of a lawyer – concentrate on specifying rules that are legally correct. You can specify multiple overlapping rules, covering special cases and general cases.

How rules determine interview process

Many people envision a guided interview as a process whereby an interviewee starts at the beginning screen, then moves through a series of screens and then arrives at the end screen of the interview. At any point in time, the interviewee is envisioned as being located at a certain “place” in the interview process.

However, when the interview is driven by rules, this way of envisioning the interview process is misleading. For example, consider the following structure for an interview:

- Ask “What is your name?”

- Ask “When were you injured?”

- If the injury took place more than two years ago, say, “Sorry, the statute of limitations has expired, so you cannot file a complaint.”

- Ask “Where did the injury take place?”

- Ask “How much did you pay in medical bills?”

- Ask “How much time did you have to take off from work?”

- etc.

- Here is a complaint you can file in court.

Suppose the user started the interview one day before the statute of limitations expired, and proceeded as far as the “How much did you pay in medical bills?” question, but then took a few days to locate their medical bills, and didn’t complete the interview until a week after the statute of limitations expired. Should the guided interview allow the user to download a complaint, or should it tell the user, “Sorry, the statute of limitations has expired, so you cannot file a complaint.”? If you think of the interview process as one where the interviewee is “located” at a particular “place” in the interview, you would say that since the user has “gone past” the part of the interview process that checked for a statute of limitations problem, the user should be allowed to proceed.

The philosophy behind docassemble is that a robust interview process is one where the “current question” in the interview is determined not by which question “comes after” the previous question, but rather by the application of a set of rules to a set of facts. If there is a legal rule about the statute of limitations, it should be applied every time the screen loads, not just once at the beginning of the interview.

In docassemble, the interview logic is envisioned more as a “checklist” than a process. Each time the screen loads, docassemble reviews the checklist. What it does next depends on the application of the checklist to the current state of affairs.

By analogy, an airplane pilot will go through a checklist prior to takeoff. Whether the airline pilot turns onto the runway or goes back to the gate depends on the application of the checklist to the state of the aircraft and external factors like the weather. Likewise, what docassemble does when the screen loads depends on the application of the interview logic (specified in the YAML) to the current state of the interview answers and external factors like the date.

From the user’s perspective, the docassemble interview process looks like something that has a beginning, an end, and a “current location,” but this is really just the by-product of docassemble running through a checklist every time the screen loads. “Do we know the user’s name? Check. Has the statute of limitations expired? Check. Do we know where the injury took place? Check.”

If you observe an airplane pilot at work, you might think, “gosh, the pilot spends so much time going through boring repetitive checklists, can’t he just grab the controls and fly the plane?” Similarly, you might look at what docassemble does every time the screen loads, and you might think, “ugh, why is it wasting time going through all of this logic, can’t it just move on to the next question?” Although the checklist method is repetitive, it is robust and is capable of catching hard-to-foresee problems.

The docassemble interview developer’s job is to design the checklist that leads to the interview process, not to specify the process directly. In most situations, this is a distinction without a difference, because the developer can write something like this:

mandatory: True

code: |

user.name.first

favorite_fruit

favorite_vegetable

final_screenThis is a checklist for what should be considered every time the screen loads: “if the name is not known, ask the name. If the favorite fruit is not known, ask for the favorite fruit. If the favorite vegetable is not known, ask for the favorite vegetable. Then show the ‘final_screen’ screen.” This translates directly into a process: “first ask for the name, then the favorite fruit, then the favorite vegetable, then show the final screen.”

In more complicated interviews, the connection between the checklist and the process is less explicit. For example:

mandatory: True

code: |

user.name.first

plaintiffs.gather()

defendants.gather()

if not jurisdiction_is_proper:

kick_out_user

final_screenIn this interview, after the user is asked for their name,

docassemble gathers a list of plaintiffs and then gathers a list

of defendants. The process of gathering groups is complex and

involves multiple question blocks. The line plaintiffs.gather()

is effectively a checklist item that means “make sure the plaintiffs

are gathered.” Groups can be gathered in a variety of ways. The

questions might be “What is the name of the first plaintiff?”, “Are

there any other plaintiffs?”, “What is the name of the second

plaintiff?”, “Are there any other plaintiffs?”, etc. The line if not

jurisdiction_is_proper implicitly triggers the defining of

jurisdiction_is_proper, which is defined by a code block.

By specifying a checklist, you can ensure the integrity of your interview’s logic, control the order of questions, and use to trigger the asking of questions that it would be too tedious to specify individually. There are things you need to think about, however, to ensure that your checklist results in a process that makes sense.

Beware of non-idempotency

When designing the checklist that docassemble runs every time the screen loads, you need to be careful about how you specify the checklist items. For example, you wouldn’t want the checklist to be the following:

- Ask for the user’s name.

- Ask for the user’s date of birth.

- Give the user an assembled document.

That would mean that every time the screen loads, it would ask for the user’s name. Instead, the checklist should be:

- If the user’s name is unknown, ask them for it.

- If the user’s date of birth is unknown, ask them for it.

- Give the user an assembled document.

When you write a checklist in Python format, it looks like this:

mandatory: True

code: |

user.name.first

user.birthdate

final_screenIn docassemble, referencing the name of a variable like

user.birthdate effectively means “if user.birthdate is undefined,

stop what we are doing and seek out a definition of user.birthdate;

otherwise, proceed to the next line.”

By contrast, if you use the force_ask() function, it will always

ask the question:

mandatory: True

code: |

force_ask('user.name.first')

force_ask('user.birthdate')

final_screenHere, the first “checklist” item says that docassemble must ask a

question to determine the value of user.name.first even if the

variable is already defined. This is not what you want to do in a

checklist; the user will be confused about why the interview asks for

their name again when they just provided it. (This is is one of the

reasons why the force_ask() function is rarely used.)

docassemble allows you to run Python functions inside of a checklist, and in most situations this works as expected. For example:

mandatory: True

code: |

user.name.first

user.birthdate

if not record_exists_in_database_for(user):

error_screen

final_screenHere, there is a function called record_exists_in_database_for()

that looks up the user based on the user’s name and birthdate. It is

ok if this function runs every time the screen loads.

However, beginning developers sometimes assume that they can do this:

mandatory: True

code: |

user.name.first

user.email

send_email(to=user, subject="Welcome", body="Welcome to the interview!")

user.birthdate

final_screenThis means that after the user provides their name and e-mail address, docassemble will send them an e-mail. However, it also means that every time the screen loads thereafter, docassemble will send another e-mail! The checklist item should have been written in such a way that the e-mail is only sent once:

mandatory: True

code: |

user.name.first

user.email

if not task_performed('welcome_email'):

send_email(to=user, subject="Welcome", body="Welcome to the interview!", task='welcome_email')

user.birthdate

final_screenThe task_performed() function, combined with the task paramater

of the send_email() function, is one way to ensure that code only

runs once. Another method is to use a separate code block that

defines a variable:

mandatory: True

code: |

user.name.first

user.email

email_sent

user.birthdate

final_screen

---

code: |

send_email(to=user, subject="Welcome", body="Welcome to the interview!")

email_sent = TrueThe logic behind the email_sent line is: “if email_sent is not

defined, run the code block in order to define it; otherwise continue

to the next line.”

Another mistake that beginning developers sometimes make is writing a checklist that results in the user seeing a different screen if they refresh the screen without providing input. For example, consider this interview:

mandatory: True

code: |

user.name.first

user.email

if not task_performed('data_stored'):

store_data(user)

mark_task_as_performed('data_stored')

user.wants_email

if user.wants_email:

send_email(to=user, template=confirmation_email)

user.birthdate

final_screen

---

question: |

Do you want a confirmation e-mail?

yesno: user.wants_emailIn this example, after the user provides their e-mail address,

docassemble will run the store_data() function, then it will

mark the data_stored “task” as having been completed, and then it

will see that user.wants_email is undefined, so it will ask the user

if they would like to receive a confirmation e-mail. Suppose that the

user, instead of answering the question, refreshes the screen. The

interview logic will be evaluated again. Now, since the data_stored

“task” has been marked as complete, the Python code skips the if

clause and asks the user for user.birthdate. But this defeats the

user’s expectation; the user reasonably expects that when they refresh

the screen, they will see the user.wants_email question again. The

problem is with the interview logic.

Software developers use the term “idempotent” to describe a system that produces the same result if an action is repeated. The interview logic in this circumstance is not idempotent because when it is repeated, a different result is produced.

Normally, your “checklist” should be designed to result in idempotent behavior. The exception would be if the passage of time has made the “current question” obsolete. For example, if the user started the interview before the statute of limitations period expired, and then tried to continue with the interview after the statute of limitations period expired, it would be reasonable for the user to see a different screen when they refreshed the screen.

Another consequence of non-idempotent logic is that users might see a

pop-up message saying “Input not processed.” This is because of a

security feature in docassemble: if the browser tries to submit

input for a question that is different from what the current

question is according to the interview logic, docassemble will

reject the browser’s attempt to change the interview answers. In the

example above, if the user clicked “Yes” or “No” in response to the

question “Do you want a confirmation e-mail?”, the user would have

seen an “Input not processed” error and been sent to the

user.birthdate question.

To fix the idempotency problem, you could take the e-mail sending code out of the conditional statement:

mandatory: True

code: |

user.name.first

user.email

if not task_performed('data_stored'):

store_data(user)

mark_task_as_performed('data_stored')

user.wants_email

if user.wants_email:

send_email(to=user, template=confirmation_email)

user.birthdate

final_screenWriting idempotent logic is also important because of the way that

docassemble runs code blocks. Consider the following

interview, which has a code block for calculating the user’s total

income:

mandatory: True

question: |

Tell me about your income and expenses.

fields:

- Benefits income: benefits_income

datatype: currency

- Business income: business_income

datatype: currency

- Business expenses: business_expenses

datatype: currency

---

mandatory: True

code: |

total_income = 0.0

---

mandatory: True

code: |

total_income = total_income + benefits_income

total_income = total_income + net_business_income

---

code: |

net_business_income = business_income - business_expenses

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Your total income is ${ currency(total_income) }.At first glance, this logic looks correct; the interview gathers

information from the user, initializes total_income to zero, then

adds the benefits income and the net business income to

total_income. However, you will find that the calculation is

incorrect; benefits_income will be counted twice.

The problem is that this code block is not idempotent:

mandatory: True

code: |

total_income = total_income + benefits_income

total_income = total_income + net_business_incomeIf this code runs more than once, the total_income will be increased

each time. If you try to run this interview, this code block will run

more than once. The first time it runs, it adds benefits_income to

total_income, but then stops because net_business_income is

undefined. docassemble obtains a definition of

net_business_income in microseconds by running the code block that

defines net_business_income. But after it does that, it does not

resume where it left off (adding net_business_income to

total_income). It will repeat the code block again, from the

beginning. So benefits_income will be added to total_income a

second time, and then net_business_income will be added, and then

the “mandatory” block will be marked as having been completed, because

it ran through all the way to the end.

If you are familiar with computer programming, docassemble works

by trapping exceptions. When Python encounters an undefined variable,

it raises an exception. docassemble traps that exception, figures

out what variable was undefined, and then tries to define it. It does

this either by asking the user a question or by running a ‘code’

block. Either way, the exception halts code execution, and Python is

unable pick up exactly where it left off when the exception was

raised.

The solution to this problem is to write the code block so that it

can be run repeatedly without making a miscalculation:

mandatory: True

code: |

total_income = 0

total_income = total_income + benefits_income

total_income = total_income + net_business_incomeThis way, the code will produce the correct total no matter how many undefined variables docassemble encounters along the way.

Inexperienced developers also sometimes make the error of assuming

that all code blocks will run to completion. For example, suppose

that the above interview was written like this, with only one

mandatory block:

question: |

Tell me about your income and expenses.

fields:

- Benefits income: benefits_income

datatype: currency

- Business income: business_income

datatype: currency

- Business expenses: business_expenses

datatype: currency

---

code: |

total_income = 0.0

total_income = total_income + benefits_income

total_income = total_income + net_business_income

---

code: |

net_business_income = business_income - business_expenses

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Your total income is ${ currency(total_income) }.This interview appears to be reasonable, but actually it contains a

flaw. When docassemble tries to show the mandatory question, it

encounters an undefined variable total_income, so it seeks out a

definition of total_income. It tries to run this code block:

code: |

total_income = 0.0

total_income = total_income + benefits_income

total_income = total_income + net_business_income

docassemble sets total_income to zero, and then encounters an

undefined variable, benefits_income, so it asks the question that

defines benefits_income. However, what if the user refreshed the

screen on the question that asks for the benefits_income?

docassemble would attempt to show the mandatory question again,

and this time total_income is defined, so docassemble can

display the screen, which says that the total income is zero. “But

wait,” you say, “it didn’t finish running the code block that

defines total_income!” True, but the rule of docassemble’s

logic is that it goes through your YAML, runs mandatory blocks

that haven’t been run before, and tries to obtain definitions for any

undefined variables that are encountered along the way. Nothing in

this rule says that it will remember if it left a code block early

and go back to it.

The moral of the story is that if you are going to use dependency

satisfaction, do not allow your dependencies to be satisfied

prematurely. The code block should be written instead as:

code: |

total_income = benefits_income + net_business_incomeor

code: |

total_income = benefits_income + net_business_income

draft_total_income = 0.0

draft_total_income = total_income + benefits_income

draft_total_income = total_income + net_business_income

total_income = draft_total_income

del draft_total_incomeYou can think of the undefined-ness of a variable as docassemble’s incentive to obtain the definition of the variable. It is like hiring a busy contractor to do work on your house; if you give the contractor his final payment after he is only halfway done with the job, he might leave at the end of the day and forget to come back later to finish the work.

You might be tempted to combine the definition of several variables in

a single code block, perhaps because you think it saves space or is

easier to read:

code: |

subtotal = 0

for item in asset:

if item.countable:

subtotal = subtotal + item.value

total_assets = subtotal

temp_list = []

for item in income:

if item.included and item.type not in income.items:

temp_list.append(item.type)

income_items = temp_list

Think about what will happen if the interview needs a value of

total_assets. It will run the code block, and halfway through,

the value of total_assets will be obtained. But the code will not

stop executing; it will go on to start building the income_items

list. This will work fine if the income list has been completely

gathered, but what if it has not been? Then the code block may

result in the asking of a question about the income list, but if the

user refreshes the screen, that question will go away. This

introduces an idempotency problem.

It is a much better practice to separate your code into single-purpose

code blocks:

code: |

subtotal = 0

for item in asset:

if item.countable:

subtotal = subtotal + item.value

total_assets = subtotal

---

code: |

temp_list = []

for item in income:

if item.included and item.type not in income.items:

temp_list.append(item.type)

income_items = temp_list

This way, no matter whether your interview needs total_assets first

or income_items first, and regardless of whether it has already

gathered income or asset, these code blocks will perform their

function and deliver a definition without causing any non-idempotent

questions to be asked.

As a general rule, let each code block serve a single purpose, or a

set of closely-related purposes, and let it deliver its award (the

defining of the variable sought) on the last line. If you get into

this habit, you will avoid hard-to-debug logic errors.

Although typically your non-mandatory code blocks should only set

one variable at a time, it is ok if they set other variables

incidentally. However, in that situation you should probably use the

only sets modifier.

For example, suppose you have an interview in which you want to ask

the user, “Do you receive income from public benefits?”, and you want

to set the variable has_benefits to the answer, but as a

double-check on the validity of the answer, you want to set

has_benefits to True during the income gathering process if the

user indicates that they have income from disability or welfare

income.

question: |

Do you receive income from public benefits?

yesno: has_benefits

---

code: |

temp_total = []

for item in income:

if item.included and item.type not in income.items:

temp_total.append(item.type)

if item.type in ['disability', 'welfare']:

has_benefits = True

total_income = temp_totalThe problem here is that the income gathering question will now be

called upon to set has_benefits. If has_benefits is needed before

total_income, the interview will start asking about income items,

but will mysteriously stop in the middle of the process if the user

enters a disability or welfare income item. Then, when total_income

is needed later in the interview, it will resume asking questions

about the income items. It would be better if you used only sets:

only sets: total_income

code: |

temp_total = []

for item in income:

if item.included and item.type not in income.items:

temp_total.append(item.type)

if item.type in ['disability', 'welfare']:

has_benefits = True

total_income = temp_totalThat way, the code block will only be called upon to define

total_income. It can still have the side effect of setting

has_benefits to True, but it will not be called upon to define

anything other than total_income.

The logical order of an interview

In the previous sections, we have explained that when docassemble

runs your interview, it goes through your YAML looking for blocks

that are mandatory, and it tries to run them in order. When it

encounters an undefined variable, it stops what it is doing and tries

to obtain a definition of that undefined variable.

If a mandatory question is answered, or a

mandatory code block’s Python code runs all the

way through to end, then docassemble remembers that the

mandatory block has been completed, and the next time it evaluates

the interview logic, it will skip over the block.

(Technical note: how does docassemble remember that a block has

been completed? It stores a variable in the interview answers, inside

of a special dictionary called _internal. In order to identify the

blocks that have been completed, it uses the block’s id. If you

do not specify an id on a mandatory block, docassemble

will generate an identifier like Question_0 or Question_1 for the

first and second blocks in your YAML file. This means that if you

have an interview that is “in production” and users have active

sessions in that interview, and then you change the YAML to insert

new blocks or move them around, you could cause these identifiers to

change, and then users who started sessions before you changed the

YAML could experience problems where questions they have already

answered are re-asked. In order to avoid this problem, make sure to

attach a unique id to each mandatory block in your interview.

That way, even if you rearrange the YAML, users with existing

sessions will not experience problems.)

In addition to mandatory, there is a second type of modifier you

can use to force a code block to be processed. If you mark a

code block with initial: True, then the block will be run every

time the screen loads, even if it has run before. The block is

“initial” in the sense that it initializes the interview logic that

will be evaluated during the screen load.

mandatory and initial blocks are evaluated in the order they

appear in the question file. Therefore, the location in the interview

of mandatory and initial blocks, relative to each other, is

important.

The order in which non-mandatory and non-initial questions

appear is usually not important. If docassemble needs a

definition of a variable, it will go looking for a block that defines

the variable.

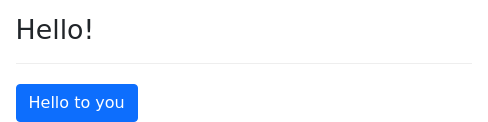

Consider the following example:

question: |

Do you like penguins?

yesno: user_likes_penguins

---

question: |

Do you like elephants?

yesno: user_likes_elephants

---

mandatory: true

question: |

Hello!

buttons:

- Hello to you: continue

---

mandatory: true

question: |

What is your name?

fields:

- Name: user_name

---

mandatory: true

question: |

Your favorite food is

${ favorite_food }.

% if user_likes_penguins:

You are a fan of penguins.

% else:

You detest penguins, for some

strange reason.

% endif

---

question: |

What is your favorite food?

fields:

- Favorite food: favorite_foodThe order of the questions is:

- Hello!

- What is your name?

- What is your favorite food?

- Do you like penguins?

The first two questions are asked because the corresponding

question blocks are marked as mandatory. They are asked in

the order in which they are asked because of the way the question

blocks are ordered in the YAML file.

The next two questions are asked implicitly. The third and final

mandatory block makes reference to two variables: favorite_food

and user_likes_penguins. Since the questions that define these

variables are not mandatory, they can appear anywhere in the YAML

file, in any order you want. In this case, the favorite_food

question block is at the end of the YAML file, and the

user_likes_penguins question block is at the start of the YAML

file.

The order in which these two questions are asked is determined by the

order of the variables in the text of the final mandatory

question. Since favorite_food is referenced first, and

user_likes_penguins is referenced afterwards, the user is asked

about food and then asked about penguins.

Note that there is also an extraneous question in the interview that

defines user_likes_elephants; the presence of this question

block in the YAML file has no effect on the interview.

Generally, you can order non-mandatory blocks in your YAML file

any way you want. You may want to group them by subject matter into

separate YAML files that you include in your main YAML file.

When your interviews get complicated, there is no natural order to

questions. In some situations, a question may be asked early, and in

other situations, a question may be asked later.

Overriding one question with another

The order in which non-mandatory blocks appear in the YAML file

is only important if you have multiple blocks that each offer to

define the same variable. In that case, the order of these blocks

relative to each other is important. When looking for blocks that

offer to define a variable, docassemble will use later-defined

blocks first. Later blocks “supersede” the blocks that came before.

This allows you to include “libraries” of questions in your

interview while retaining the ability to customize how any particular

question is asked.

As explained in the initial blocks section, the effect of an

include block is basically equivalent to copying and pasting the

contents of the included file into the original file.

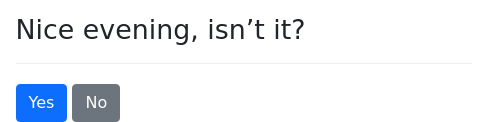

For example, suppose that there is a YAML file called

question-library.yml, which someone else wrote, which consists of

the following questions:

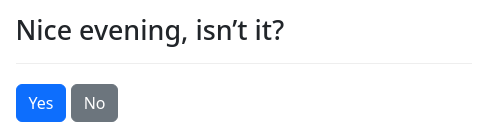

question: |

Nice evening, isn't it?

yesno: user_agrees_it_is_a_nice_evening

---

question: |

Interested in going to the dance tonight?

yesno: user_wants_to_go_to_danceYou can write an interview that uses this question library:

include:

- question-library.yml

---

mandatory: True

code: |

if user_agrees_it_is_a_nice_evening and user_wants_to_go_to_dance:

good_news

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Say, I have to run. Bye!

---

event: good_news

question: |

That is splendid news!When docassemble needs to know the definition of

user_agrees_it_is_a_nice_evening or user_wants_to_go_to_dance, it

will be able to find a block in question-library.yml that offers to

define the variable.

Suppose, however, that you thought of a better way to ask the

user_wants_to_go_to_dance question, but you don’t want to get rid of

question-library.yml entirely. You could override the

user_wants_to_go_to_dance question in question-library.yml by

doing the following:

include:

- question-library.yml

---

question: |

So, about that dance tonight . . .

wanna go?

yesno: user_wants_to_go_to_dance

---

mandatory: True

code: |

if user_agrees_it_is_a_nice_evening and user_wants_to_go_to_dance:

good_news

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Say, I have to run. Bye!

---

event: good_news

question: |

That is splendid news!This interview file loads the two questions defined in

question-library.yml, but then, later in the list of questions,

provides a different way to get the value of

user_wants_to_go_to_dance. When docassemble goes looking for a

question to provide a definition of user_wants_to_go_to_dance, it

starts with the questions that were defined last, and it will

prioritize your question over the question in question-library.yml.

Your question block takes priority because it is located later in

the YAML file.

This is similar to the way law works: old laws do not disappear from the law books, but they can get superseded by newer laws. “Current law” is simply “old law” that has not yet been superseded.

A big advantage of this feature is that you can include “libraries” written by other people without having to edit those other files in order to tweak them. You can use another person’s work without taking on the responsibility of maintaining that person’s work over time; you can just incorporate by reference that person’s file, which they continue to maintain.

For example, if someone else has developed interview questions that determine a user’s eligibility for food stamps, you can incorporate by reference that developer’s YAML file into an interview that assesses whether a user is maximizing his or her public benefits. When the law about food stamps changes, that developer will be responsible for updating his or her YAML file; your interview will not need to change. This allows for a division of labor. All you will need to do is make sure that the docassemble package containing the food stamp YAML file gets updated on the server when the law changes.

Fallback questions

If a code block does not, for whatever reason, actually define the

variable, docassemble will “fall back” to a block that is located

earlier in the YAML file. For example:

include:

- question-library.yml

---

question: |

I forgot, did we already agree to go to the dance together?

yesno: we_already_agreed_to_go

---

code: |

if we_already_agreed_to_go:

user_wants_to_go_to_dance = True

---

mandatory: True

code: |

if user_agrees_it_is_a_nice_evening and user_wants_to_go_to_dance:

good_news

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Say, I have to run. Bye!

---

event: good_news

question: |

That is splendid news!In this case, when docassemble tries to get a definition of

user_wants_to_go_to_dance, it will first try running the code

block, and then it will encounter we_already_agreed_to_go and seek

its definition. If the value of we_already_agreed_to_go turns out

to be false, the code block will run its course without setting a

value for user_wants_to_go_to_dance. Not giving up,

docassemble will keep going backwards through the blocks in the

YAML file, looking for one that offers to define

user_wants_to_go_to_dance. It will find such a question among the

questions included by reference from question_library.yml, namely

the question “Interested in going to the dance tonight?”

This “fall back” process can also happen with special question

blocks that use the continue option.

include:

- question-library.yml

---

question: Which of these statements is true?

choices:

- "I am old-fashioned":

question: |

My darling, would you do me the

honor of accompanying me to

the dance this fine evening?

yesno: user_wants_to_go_to_dance

- "I don't care for flowerly language": continue

---

mandatory: True

code: |

if user_agrees_it_is_a_nice_evening and user_wants_to_go_to_dance:

good_news

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Say, I have to run. Bye!

---

event: good_news

question: |

That is splendid news!In this case, the special continue choice causes docassemble

to skip the question block and look elsewhere for a definition of

user_wants_to_go_to_dance. docassemble will “fall back” to the

version of the question that exists within question-library.yml.

When looking for a block that offers to define a variable,

docassemble starts at the bottom and works its way up.

(Note that questions using continue are of limited utility

because they cannot use the generic object modifier or index

variables. However, code blocks do not have this limitation.)

So, to recapitulate: when docassemble considers what blocks it

must process, it goes from top to bottom through your interview

YAML file, looking for mandatory and initial blocks; if a

block is later in the file, it is processed later in time. However,

when docassemble considers what question it should ask to define a

particular variable, it goes from bottom to top; if a block is later

in the file, it is considered to “supersede” blocks that are earlier

in the file.

As explained below, however, instead of relying on relative placement of blocks in the YAML file, you can explicitly indicate which blocks take precedence over other blocks.

How docassemble runs your code

docassemble goes through your interview YAML file from start to

finish, incorporating included files as it goes. It always

executes initial code when it sees it. It executes any

mandatory code blocks that have not been

successfully executed yet. If it encounters a

mandatory question that it has not been

successfully asked yet, it will stop and ask the question.

If at any time it encounters a variable that is undefined, for example while trying to formulate a question, it will interrupt itself in order to go find the a definition for that variable.

Whenever docassemble comes back from one of these excursions to find the definition of a variable, it does not pick up where it left off; it starts from the beginning again.

Therefore, when writing code for an interview, you need to keep in mind that any particular block of code may be re-run from the beginning multiple times.

For example, consider the following code:

---

mandatory: True

code: |

if user_has_car:

user_net_worth = user_net_worth + resale_value_of_user_car

if user_car_brand == 'Toyota':

user_is_sensible = True

elif user_car_is_convertible:

user_is_sensible = False

---The intention of this code is to increase the user’s net worth by the resale value of the user’s car, if the user has a car. If the code only ran once, it would work as intended. However, because of docassemble’s design, which is to ask questions “as needed,” the code actually runs like this:

- docassemble starts running the code; it encounters

user_has_car, which is undefined. It finds a question that definesuser_has_carand asks it. (We will assumeuser_has_caris set to True.) - docassemble runs the code again, and tries to increment the

user_net_worth(which we can assume is already defined); it encountersresale_value_of_user_car, which is undefined. It finds a question that definesresale_value_of_user_carand asks it. - docassemble runs the code again. The value of

user_net_worthis increased. Then the code encountersuser_car_brand, which is undefined. It finds a question that definesuser_car_brandand asks it. - docassemble runs the code again. The value of

user_net_worthis increased (again). Ifuser_car_brandis equal to “Toyota,” thenuser_is_sensibleis set. In that case, the code runs successfully to the end, and themandatorycode block is marked as completed, so that it will not be run again. - However, if

user_car_brandis not equal to “Toyota,” the code will encounteruser_car_is_convertible, which is undefined. docassemble will find a question that definesuser_car_is_convertibleand ask it. docassemble will then run the code again, the value ofuser_net_worthwill increase yet again, and then (finally) the code will run successfully to the end.

The solution here is to make sure that your code is prepared to be

stopped and restarted. For example, you could have a separate code

block to compute user_net_worth:

---

mandatory: True

code: |

user_net_worth = 0

if user_has_car:

user_net_worth = user_net_worth + resale_value_of_user_car

if user_has_house:

user_net_worth = user_net_worth + resale_value_of_user_house

---Note that mandatory must be true for this to work sensibly.

If this were an optional code block, it would not run to completion

because user_net_worth would already be defined when docassemble

came back from asking whether the user has a car.

How docassemble finds questions for variables

There can be multiple questions or code blocks in an interview that

can define a given variable. You can write generic object

questions in order to define attributes of objects, and you can use

index variables to refer to any given item in a DAList or

DADict (or a subtype of these objects). Which one will be used?

In general, if you have multiple questions or code blocks that are capable of defining a variable, docassemble will try the more specific ones first, and then the more general ones.

For example, if the interview needs a definition of

fruit['a'].seed_info.tally['b'].molecules[4].name, it will look for

questions that offer to define the following variables, in this order:

fruit['a'].seed_info.tally['b'].molecules[4].name

fruit[i].seed_info.tally['b'].molecules[4].name

fruit['a'].seed_info.tally[i].molecules[4].name

fruit['a'].seed_info.tally['b'].molecules[i].name

fruit[i].seed_info.tally[j].molecules[4].name

fruit[i].seed_info.tally['b'].molecules[j].name

fruit['a'].seed_info.tally[i].molecules[j].name

fruit[i].seed_info.tally[j].molecules[k].nameThen it will look for generic object blocks that offer to define

the following variables, in this order:

x['a'].seed_info.tally['b'].molecules[4].name

x[i].seed_info.tally['b'].molecules[4].name

x['a'].seed_info.tally[i].molecules[4].name

x['a'].seed_info.tally['b'].molecules[i].name

x[i].seed_info.tally[j].molecules[4].name

x[i].seed_info.tally['b'].molecules[j].name

x['a'].seed_info.tally[i].molecules[j].name

x[i].seed_info.tally[j].molecules[k].name

x.seed_info.tally['b'].molecules[4].name

x.seed_info.tally[i].molecules[4].name

x.seed_info.tally['b'].molecules[i].name

x.seed_info.tally[i].molecules[j].name

x.tally['b'].molecules[4].name

x.tally[i].molecules[4].name

x.tally['b'].molecules[i].name

x.tally[i].molecules[j].name

x['b'].molecules[4].name

x[i].molecules[4].name

x['b'].molecules[i].name

x[i].molecules[j].name

x.molecules[4].name

x.molecules[i].name

x[4].name

x[i].name

x.nameMoreover, when docassemble searches for a generic object

question for a given variable, it first look for generic object

questions with the object type of x (e.g., Individual). Then it

will look for generic object questions with the parent type of

object type of x (e.g., Person). It will keep going through the

ancestors, stopping at the most general object type, DAObject.

Note that the order of questions or code blocks in the YAML matters

where the variable name is the same; the blocks that appear later in

the YAML will be tried first. But when the variable name is

different, the order of the blocks in the YAML does not matter.

If your interview has a question that offers to define

seeds['apple'] and another question that offers to define

seeds[i], the seeds['apple'] question will be tried first,

regardless of where the question is located in the the YAML.

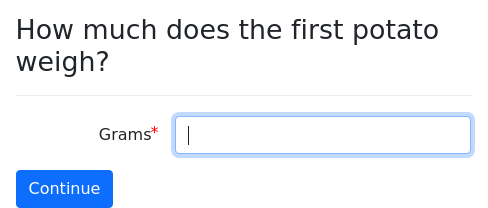

Here is an example in which a relatively specific question, which sets

veggies[i][1], will be used instead of a more general question,

which sets veggies[i][j], when applicable:

question: |

How much does the other

${ i } weigh?

fields:

- Grams: veggies[i][1]

datatype: number

---

question: |

How much does the

${ ordinal(j) }

${ i } weigh?

fields:

- Grams: veggies[i][j]

datatype: numberThese rules about which blocks are tried

before other blocks can be overriden using the order initial block

or the id and supersedes modifiers. You can use the if

modifier to indicate that a given question should only be asked

under certain conditions. You can use the scan for variables

modifier to indicate that a question or code block should

only be considered when looking to define a particular variable or set

of variables, even though it is capable of defining other variables.

Specifiers that control interview logic

mandatory

By default, all blocks in an interview are optional; they will be

called upon only if needed to retrieve the value of a variable.

However, if all blocks are optional, the interview has nothing to do.

You can use the mandatory modifier to indicate that a block must be

run. The first mandatory block in your interview will be the

starting point of the interview logic when the user first starts the

interview.

Consider the following as a complete interview file:

---

question: What is the capital of Maine?

fields:

- Capital: maine_capital

---

question: Are you sitting down?

yesno: user_sitting_down

mandatory: True

---

question: Your socks do not match.

mandatory: True

---The interview will ask “Are you sitting down” and then it will say “Your socks do not match.” It will not ask “What is the capital of Maine?”

Another way to control the logic of an interview is to have a single,

simple mandatory code block that sets the

interview in motion.

For example:

---

mandatory: True

code: |

if user_sitting_down:

user_informed_that_socks_do_not_match

else:

user_will_not_sit_down

---

question: What is the capital of Maine?

fields:

- Capital: maine_capital

---

question: Are you sitting down?

yesno: user_sitting_down

---

question: Your socks do not match.

sets: user_informed_that_socks_do_not_match

---

question: You really should have sat down.

subquestion: I had something important to tell you.

sets: user_will_not_sit_down

---Here, the single mandatory block contains simple Python code that

contains the entire logic of the interview.

If a mandatory specifier is not present within a block, it is as

though mandatory was set to False.

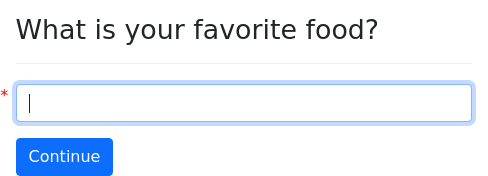

The value of mandatory can be a Python expression. If it is a

Python expression, the question or code block will be

treated as mandatory if the expression evaluates to a true value.

mandatory: |

favorite_food == "apples"

question: |

You have good taste in food.

buttons:

- Continue: continue

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Thank you for your input.

---

question: |

What is your favorite food?

fields:

- no label: favorite_foodIt is a best practice to tag all mandatory blocks with an id.

initial

The initial modifier causes the code block to be run every time

docassemble processes your interview (i.e., every time the screen

loads during an interview). mandatory blocks, by contrast, are

never run again during the session if they are successfully “asked”

once. docassemble executes the code in an initial block in

the same way it executes the code of mandatory blocks, except that

running to completion does not mean the block will not be executed again.

initial blocks should be used in the following situations:

- “Initializing” the Python context in a multi-user interview

depending on who the user is. For example, if your interview uses a

variable

userthat should always refer to anIndividualobject corresponding to the user, you can write aninitialblock that looks atuser_info().emailto figure out who the logged-in user is. - When you are using the actions feature and you want to make sure the actions are processed only in particular circumstances.

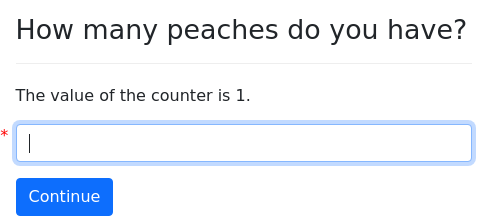

Here is an example that illustrates how initial blocks work:

mandatory: True

code: |

counter = 0

---

initial: True

code: |

counter = counter + 1

---

question: |

How many peaches do you have?

subquestion: |

The value of the counter

is ${ counter }.

fields:

- no label: peaches

datatype: integer

---

code: |

fruits = peaches + pears

---

question: |

How many pears do you have?

subquestion: |

The value of the counter

is ${ counter }.

fields:

- no label: pears

datatype: integer

---

question: |

You have ${ fruits } pieces of fruit.

subquestion: |

The value of the counter

is ${ counter }.

mandatory: TrueNote in this example that from screen to screen, the counter

increments from 1 to 3 and then to 6. The counter does not count the

number of screens displayed, but rather the number of times the

interview logic was evaluated. The number of times the interview logic

gets evaluated is hard to predict, but you can count on it being

evaluated many times, so you need to make sure you write your logic in

an idempotent manner.

On every screen load, the interview logic is evaluated prior to

processing the input in order to ensure that the input is responding

to whatever the current question is. docassemble needs to

evaluate the interview logic in order to know what the current

question is. It is then evaluated after the input is processed, so

that the user can be presented with the next question. In addition,

the interview logic will be re-evaluated when an undefined variable is

encountered and a code block provides the value of a variable.

- The interview logic is evaluated, but the evaluation stops when the

undefined variable

fruitis encountered. The interview then tries to run thecodeblock to getfruit, but encounters an undefined variablepeaches, so it asks a question to gatherpeaches. - The interview logic is evaluated, but the evaluation stops when the

undefined variable

fruitis encountered. The interview then tries to run thecodeblock to getfruit, but encounters an undefined variablepears, so it asks a question to gatherpears. - The interview logic is evaluated, but the evaluation stops when the

undefined variable

fruitis encountered. The interview then runs thecodeblock, and this time,fruitis successfully defined. - The interview logic is evaluated again, and the final question is displayed.

Like mandatory, initial can be set to True, False, or to

Python code that will be evaluated to see whether it evaluates to a

true or false value.

If your interview has a single mandatory code block and it is

incapable of running to completion, then you don’t really need an

initial block because you can put the logic that needs to run every

time the screen loads at the beginning of that mandatory block.

need

The need specifier allows you to manually specify the prerequisites

of a question or code block. This can be helpful for tweaking

the order in which questions are asked.

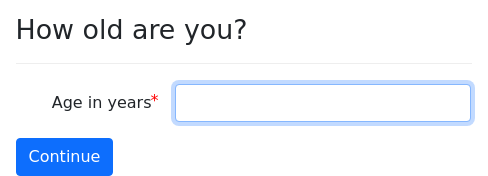

mandatory: True

need:

- number_of_years_old

- favorite_animal

question: |

Thank you for that information.

subquestion: |

My favorite animal is

${ favorite_animal },

too!

% if number_of_years_old < 10:

You're growing so fast. Pretty

soon you'll be driving a

${ favorite_color } car!

% endifIn this example, the ordinary course of the interview logic would ask

“What is your favorite animal?” as the first question. However,

everyone knows that the first question you should ask of a child is

“How old are you?” The need specifier indicates that before

docassemble should even try to present the “Thank you for that

information” screen, it should ensure that number_of_years_old old

is defined, then ensure that favorite_animal, and then try to

present the screen.

The variables listed in a need specifier do not have to actually be

used by the question. Also, if your question uses variables that are

not mentioned in the need list, docassemble will still pursue

definitions of those variables.

If any of the variables listed under need are undefined,

docassemble will obtain their definitions before processing the

content of the question. For example, suppose you have the

following question:

need:

- favorite_fruit

question: |

Your favorite apple is ${ favorite_apple }.

continue button field: fruit_verifiedIf both favorite_fruit and favorite_apple are undefined, the

definition of favorite_fruit will be sought first.

What if you wanted favorite_fruit to be sought after

favorite_apple? To do this, you can use the following special form

of need:

need:

post:

- favorite_fruit

question: |

Your favorite apple is ${ favorite_apple }.

continue button field: fruit_verifiedIn this case, the definition of favorite_fruit will be sought after

all of the prerequisites of the question have been satisfied.

You can organize your need items into pre and post items:

need:

pre:

- favorite_vegetable

post:

- favorite_fruitYou can also include post among a list of other items:

need:

- favorite_vegetable

- post:

- favorite_fruitdepends on

The depends on specifier indicates that if the listed variables

change, the results of the question or code block should be

invalidated.

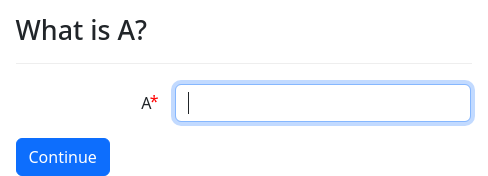

question: |

What is A?

fields:

- A: a

datatype: number

---

question: |

What is the square of ${ a }?

fields:

- B: b

datatype: number

depends on:

- a

---

code: |

c = a + b

depends on:

- a

- b

---

event: review_screen

skip undefined: False

question: |

Review your answers.

review:

- label: Edit A

field: a

button: |

A is ${ a }.

- label: Edit B

field: b

button: |

B is ${ b }.

- note: |

C is ${ c }.

---

mandatory: True

code: |

need(a, b, c)

review_screenIn this example, if the user goes through the interview to the end,

but then edits a, then if and when a is changed to a different

value, c and b will be undefined. The original value of b will

be remembered, so that when the interview logic asks the question to

define b, the original value will be presented as a default. When

a is set, c is also undefined, so that when the interview logic

requires a definition of c, the code block will be run to

recompute the value of c.

If the user goes through the interview and then edits b, a change in

b will trigger the invalidation of c.

The depends on specifier will also cause variables to be invalidated

when they are changed by a code block.

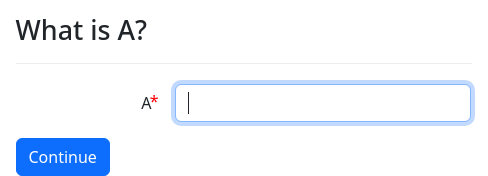

question: |

What is A?

fields:

- A: a

datatype: number

---

code: |

b = a * a

depends on:

- a

---

code: |

c = a + b

depends on:

- a

- b

---

event: review_screen

skip undefined: False

question: |

Review your answers.

review:

- label: Edit A

field: a

button: |

A is ${ a }.

- note: |

B is ${ b }.

- note: |

C is ${ c }.

---

mandatory: True

code: |

need(a, b, c)

review_screenIn this interview, the variable b is set by a code block. If

the user edits a to a different value, the depends on specifier on

the code block causes the code block to be re-run. The change

in b causes the value of c to be invalidated. As a result, c is

automatically updated when a changes.

Note that the depends on specifier results in invalidation when a

variable is changed, not when it is defined. If a variable is

undefined and is then defined, this is not considered a change for

purposes of the depends on specifier. If a user presses Continue on

a screen but does not change the value of a variable, the depends on

logic is not triggered.

The depends on specifier can be used with iterator variables.

objects:

- people: DAList.using(object_type=Individual, there_are_any=True, complete_attribute='complete')

---

question: |

How much does ${ people[i] }

get paid per pay period?

fields:

- Amount: people[i].income

datatype: currency

depends on:

- people[i].pay_period

---

question: |

How frequently does

${ people[i] } get paid?

fields:

- no label: people[i].pay_period

datatype: number

choices:

- Monthly: 12.0

- Biweekly: 26.0

- Semi-monthly: 24.0

- Weekly: 52.0

---

code: |

people[i].annual_income = people[i].income * people[i].pay_period

depends on:

- people[i].pay_period

- people[i].income

---

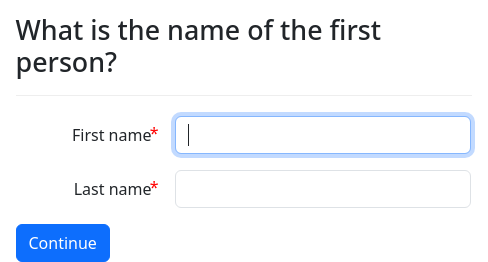

question: |

What is the name of the

${ ordinal(i) } person?

fields:

- First name: people[i].name.first

- Last name: people[i].name.last

---

code: |

people[i].name.first

people[i].annual_income