To help you organize groups of things, docassemble offers three data structures: lists, dictionaries, and sets. These mirror the list, dict, and set data types that exist in Python.

Overview of types of data structures

Lists in Python

A “list” is a group that has a defined order. Elements are numbered with an index that starts from zero. In Python, if a list is defined as:

fruit = ['apple', 'orange', 'pear']then fruit[0] will return 'apple', fruit[1] will return 'orange',

and fruit[2] will return 'pear'. You can try this out in a

Python interpreter:

>>> fruit = ['apple', 'orange', 'pear']

>>> fruit[0]

'apple'

>>> fruit[1]

'orange'

>>> fruit[2]

'pear'Adding a new element to the list is called “appending” to the list.

>>> fruit = ['apple', 'orange', 'pear']

>>> fruit.append('grape')

>>> fruit

['apple', 'orange', 'pear', 'grape']

>>> sorted(fruit)

['apple', 'grape', 'orange', 'pear']The sorted() function is a built-in Python function that

arranges a list in order.

In docassemble, lists are typically defined as special objects

of type DAList, which behave much like Python lists.

Dictionaries in Python

A “dictionary” is a group of key/value pairs. By analogy with an actual dictionary, the “key” represents the word and the “value” represents the definition. In Python, if a dictionary is defined as:

feet = {'dog': 4, 'human': 2, 'bird': 2}then feet['dog'] will return 4, feet['human'] will return 2,

and feet['bird'] will return 2. The keys are 'dog', 'human', and

'bird', and the values are 4, 2, and 2, respectively.

>>> feet = {'dog': 4, 'human': 2, 'bird': 2}

>>> feet['dog']

4

>>> feet['human']

2

>>> feet['bird']

2

>>> feet.keys()

['dog', 'human', 'bird']

>>> feet.values()

[4, 2, 2]

>>> for key, val in feet.items():

... print("{animal} has {feet} feet".format(animal=key, feet=val))

...

dog has 4 feet

human has 2 feet

bird has 2 feetThe keys of a dictionary are unique. Setting feet['rabbit'] = 4

will add a new entry to the above dictionary, whereas setting

feet['dog'] = 3 will change the existing entry for 'dog'. The

items in a dictionary are “unordered,” so if you want to loop through

them in a particular order, you will need to take special steps to

ensure the items appear in that order, such as keeping a separate

list of the keys in your desired order.

In docassemble, dictionaries are typically objects of type

DADict, which behave much like Python dicts.

Sets in Python

A “set” is a group of unique items with no order. There is no

index or key that allows you to refer to a particular item; an item is

either in the set or is not. (A set in Python behaves much like a set

in mathematical set theory.) In Python, a set can be defined with

a statement like colors = set(['blue', 'red']). Adding a new item to

the set is called “adding,” not “appending.” For example:

colors.add('green'). If you add an item to a set when the item is

already in the set, this will have no effect on the set.

>>> colors = set(['blue', 'green', 'red'])

>>> colors

set(['blue', 'green', 'red'])

>>> colors.add('blue')

>>> colors

set(['blue', 'green', 'red'])

>>> colors.remove('red')

>>> colors

set(['blue', 'green'])In docassemble, sets are typically objects of type DASet,

which behave much like Python sets.

Lists, dictionaries, and sets in docassemble

When you want to gather information from the user into a list,

dictionary, or set, you should use the objects DAList, DADict,

and DASet (or subtypes thereof) instead of Python’s basic

list, dict, and set data types. These objects have special

attributes that help interviews find the right blocks to use to

populate the items of the group.

If you want to, you can use Python’s basic list, dict, and set

data types in your interviews; nothing will stop you – but there are

no special features to help you gather information into these data

structures using question blocks or code blocks.

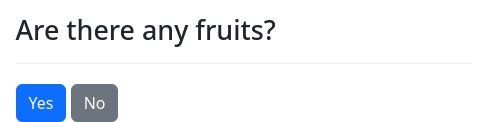

Gathering information into lists

The following interview populates a list of fruits.

objects:

- fruit: DAList

---

mandatory: True

question: |

There are ${ fruit.number_as_word() }

fruits in all.

subquestion: |

The fruits are ${ fruit }.

---

question: |

Are there any fruit that you would like

to add to the list?

yesno: fruit.there_are_any

---

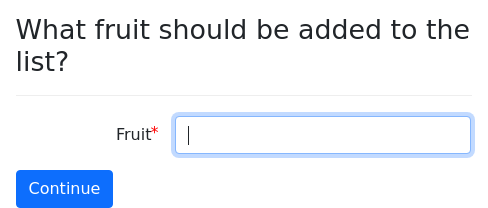

question: |

What fruit should be added to the list?

fields:

- Fruit: fruit[i]

---

question: |

So far, the fruits include ${ fruit }.

Are there any others?

yesno: fruit.there_is_anotherThe variable fruit is defined as a DAList

object.

objects:

- fruit: DAListAn objects block is like a code block, except that it performs

a special purpose of defining docassemble objects. If

docassemble needs to know the definition of the variable fruit,

it will use this block and initialize fruit as a DAList. (If you

are familiar with Python, you can think of this as a block that runs

fruit = DAList('fruit') where DAList is a Python class.)

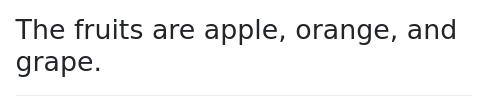

The next block contains the end point of the interview, a screen that says how many fruits are in the list and lists them.

mandatory: True

question: |

There are ${ fruit.number_as_word() }

fruits in all.

subquestion: |

The fruits are ${ fruit }.Since this question is mandatory, docassemble tries to ask

it. However, it encounters fruit.number_as_word(), which returns

the number of items in the list (e.g., “two,” “three,” etc.). But in

order to know how many items are in the list, docassemble needs to

ask the user what those items are. So the reference to

fruit.number_as_word() will implicitly trigger the process of asking

questions to gather the list. The reference to ${ fruit } would

also trigger the same process, but docassemble will encounter

fruit.number_as_word() first.

Behind the scenes, when fruit.number_as_word() is run, and

docassemble needs the list to be gathered, it runs

fruit.gather(), a gathering algorithm. The .gather() method

orchestrates the gathering process by triggering the seeking of

variables necessary to gather the list.

Many things other than ${ fruit.number_as_word() will implicitly

trigger the gathering of the fruit list. If you iterate on fruit,

or run a method that uses the items in the list, this will trigger

gathering. The advantage of implicit triggering is that your code can

be concise, and your interview will be parsimonious about whether to

ask questions to gather the list; if you have no code that requires

knowing the items in the list, then the gathering questions will not

be asked. If you want to be explicit about when the list-gathering

questions are asked, you can call fruit.gather() yourself, perhaps

in a mandatory code block.

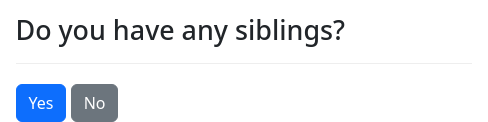

The gathering algorithm behaves like a lawyer interrogating a witness.

“Do you have any children?” asks the lawyer.

“Yes,” answers the witness.

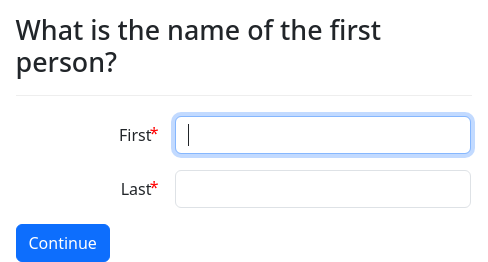

“What is the name of your first child?”

“James.”

“Besides James, do you have any other children?”

“Yes”

“What is the name of your second child?”

“Charlotte.”

“Besides James and Charlotte, do you have any other children?”

“No”

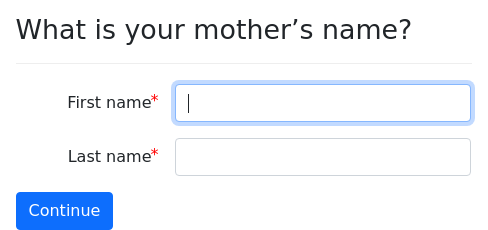

The .gather() method triggers these questions by seeking the

values of various variables:

fruit.there_are_any: should there be any items in the list at all?fruit[i]: the name of theith fruit in the list.fruit.there_is_another: are there any more fruits that still need to be added?

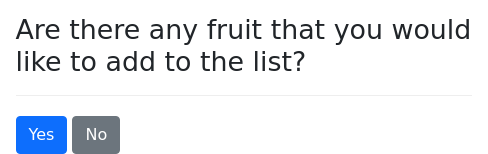

First, the interview will want to know whether there are any items in

the list at all. It will seek a definition for fruit.there_are_any.

Thus, it will ask the question, “Are there any fruit that you would

like to add to the list?”

question: |

Are there any fruit that you would like

to add to the list?

yesno: fruit.there_are_anyIf the answer to this is True, the interview will seek a definition

for fruit[0] to gather the first element. Thus, it will ask the

question “What fruit should be added to the list?”

question: |

What fruit should be added to the list?

fields:

- Fruit: fruit[i]This question uses the index variable i. The special

variable i means that the question is generalized; it can be used

and re-used for any i (0, 1, 2, 3, etc.). docassemble’s

gathering process automatically takes care of setting the variable i

to the right value before using this question.

Assume the user enters “apples.”

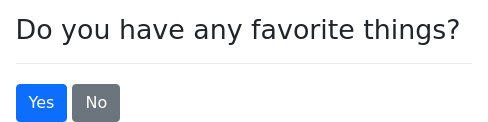

Now docassemble knows the first item in the list, but it does not

know if the list is complete yet. Therefore, it will seek a

definition for fruit.there_is_another. It will ask the question “So

far, the fruits include apples. Are there any others?”

question: |

So far, the fruits include ${ fruit }.

Are there any others?

yesno: fruit.there_is_anotherIf the answer to this is True, the interview will seek a definition

of fruit[1] to gather the second item in the list. It will ask,

again, “What fruit should be added to the list?” Assume the user

enters “oranges.”

Then the interview will again seek the definition of

fruit.there_is_another. This time, if the answer is False, then

the fruit.gather() method will return without asking any questions,

and fruit.number_as_word() will respond with the the number of items

in fruit (in this case, 2). When docassemble later encounters

The fruits are ${ fruit }., it will attempt to reduce the variable

fruit to text. Since the interview knows that there are no more

elements in the list, it does not need to ask any further questions.

${ fruit } will result in apples and oranges.

Note that the variable i is a special variable in

docassemble. When the interview seeks a definition for

fruit[0], the interview will first look for a question that offers

to define fruit[0]. If it does not find one, it will take a more

general approach and look for a question that offers to define

fruit[i]. The question that offers to define fruit[i] will be

reused as many times as necessary.

Since the index variable i is a special variable, you should never

attempt to set it yourself; you will likely get a confusing error if

you try.

Nor should you ever use i in mandatory or initial blocks.

The use of i is reserved for blocks that docassemble calls upon

when it is seeking to define a variable with an index, such as

fruit[2], and there is no block that explicitly defines fruit[2].

If you use i in a mandatory block, you will get an error that

i is undefined, or if i is defined, it might be defined as a value

that makes no sense for the context in which you are using i.

For more information on using variables like i, see the sections on

index variables and how docassemble finds questions for variables.

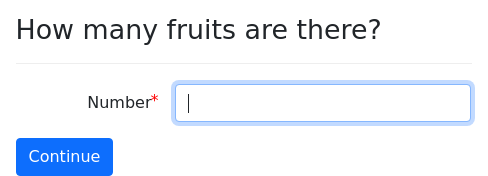

Customizing the way information is gathered

The way that docassemble asks questions to populate a list like

fruit can be customized by setting attributes of fruit. For

example, perhaps you would prefer that the questions in the interview

go like this:

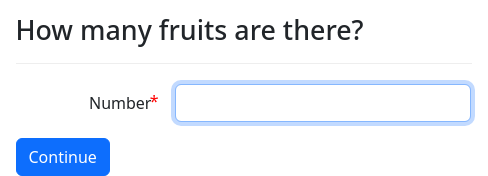

- How many fruits are there?

- What is the name of the first fruit?

- What is the name of the second fruit?

- etc.

To ask questions this way, set the .ask_number attribute of

fruit to True. Also include a question that asks “How many fruits

are there?” and use fruit.target_number as the variable set by the

question. (The .target_number attribute is a special attribute,

like .there_is_another.)

objects:

- fruit: DAList.using(ask_number=True)

---

question: |

How many fruits are there?

fields:

- Number: fruit.target_number

datatype: integer

min: 2

---

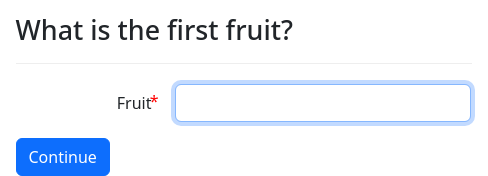

question: |

What is the name of the

${ ordinal(i) } fruit?

subquestion: |

% if fruit.number_gathered() > 0:

So far, you have mentioned ${ fruit }.

% endif

fields:

- Fruit: fruit[i]

---

mandatory: True

question: |

There are ${ fruit.number() }

fruits in all.

subquestion: |

The fruits are ${ fruit }.This example uses the using() method to initialize the

ask_number attribute of fruit. Another way to initialize the

attribute would be to use a mandatory block at the start of the

interview:

mandatory: True

code: |

fruit.ask_number = TrueGenerally, it is best to use the using() method.

You can avoid the .there_are_any

question by setting the .minimum_number to a value:

objects:

- fruit: DAList.using(minimum_number=2)Gathering a list of objects

The examples above have gathered simple variables (e.g., 'apple',

'orange') into a list. You can also gather objects into a list.

You can do this by setting the .object_type of a DAList (or

subtype thereof) to the type of object you want the items of the list

to be.

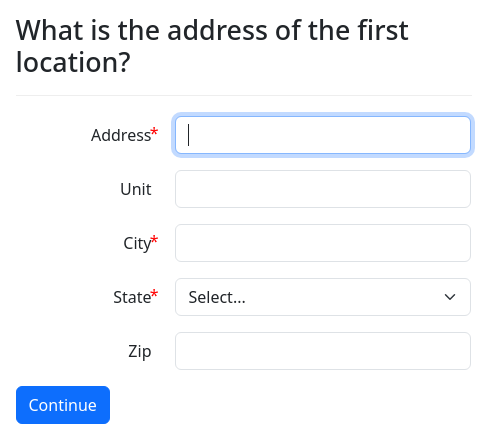

In this example, we gather Address objects into a DAList by

setting the .object_type attribute to Address.

objects:

- location: |

DAList.using(

object_type=Address,

there_are_any=True)

---

mandatory: True

question: |

The locations

subquestion: |

% for loc in location:

* ${ loc }

% endfor

---

question: |

What is the address of the

${ ordinal(i) } location?

fields:

- Address: location[i].address

- Unit: location[i].unit

required: False

- City: location[i].city

- State: location[i].state

code: |

states_list()

- Zip: location[i].zip

required: False

---

question: |

Would you like to add another location?

yesno: location.there_is_anotherThere are some list types that have an .object_type by default. For

example, DAEmailRecipientList lists have an .object_type of

DAEmailRecipient.

objects:

- recipient: |

DAEmailRecipientList.using(

there_are_any=True)

---

mandatory: True

question: |

The list of recipients

subquestion: |

% for x in recipient:

* ${ x }

% endfor

---

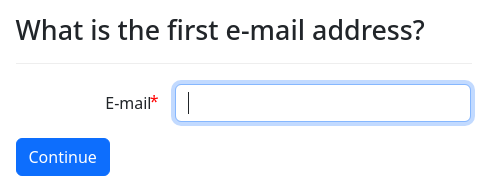

question: |

What is the ${ ordinal(i) } e-mail

address?

fields:

- E-mail: recipient[i].address

datatype: email

---

question: |

Would you like to add another

e-mail recipient?

yesno: recipient.there_is_anotherDuring the gathering process, docassemble only gathers the attributes necessary to display each object as text (by default). So if you do:

objects:

- friend: DAList.using(object_type=Individual)then the list will consist of Individuals, and docassemble

will gather friend[i].name.first for each item in the list. This is

because of the way that the Individual object works: if y is an

Individual, then its textual representation (e.g., including

${ y } in a Mako template, or calling str(y) in Python code) will

run y.name.full(), which, at a minimum, requires a definition for

y.name.first. (See the documentation for Individual for more

details.) Other object types behave differently. For example,

if y is an Address, including ${ y } in a Mako template will

result in y.block(), which depends on the address, city, and

state attributes. If you use a plain DAObject as the

object_type, then no questions will be asked; this is because

the DAObject is meant to be a “base class,” with no meaningful

attributes of its own. Thus, calling str(y) on a plain DAObject

will simply return a name based on the variable name; no questions

will be asked.

If your interview has a list of Individuals and uses attributes of

the Individuals besides the name, docassemble will eventually

gather those additional attributes, but it will ask for the names

first and only when it is done asking for the names of each individual

in the list will it start asking about the other attributes. Here is

an interview that does this:

objects:

- friend: |

DAList.using(

object_type=Individual,

there_are_any=True)

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Your friends

subquestion: |

% for x in friend:

* ${ x } likes

${ noun_plural(x.favorite_animal).lower() }

and is

${ x.age_in_years() }

years old.

% endfor

---

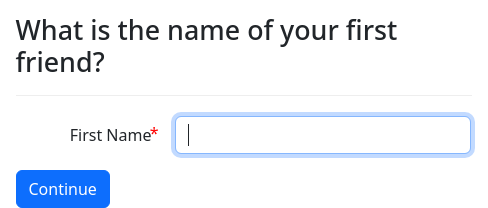

question: |

What is the name of your ${ ordinal(i) }

friend?

fields:

- First Name: friend[i].name.first

---

question: |

What is

${ friend[i].possessive('birthdate') }?

fields:

- Birthdate: friend[i].birthdate

datatype: date

---

question: |

What is

${ friend[i].possessive('favorite animal') }?

fields:

- Favorite animal: friend[i].favorite_animal

---

question: |

Do you have any other friends?

yesno: friend.there_is_anotherThe order of the questions is:

- What is the name of your first friend?

- Do you have any other friends?

- What is the name of your second friend?

- Do you have any other friends?

- What is Fred’s favorite animal?

- What is Fred’s birthdate?

- What is Sally’s favorite animal?

- What is Sally’s birthdate?

If you would prefer that all of the

questions about each individual be asked together, you can use the

.complete_attribute attribute to tell docassemble that an item

is not completely gathered until a particular attribute of that item

(usually .complete) is defined. You can then write a code block

that defines this attribute. You can use this code block to

ensure that all the questions you want to be asked are asked during

the gathering process.

In the above example, we can accomplish this by doing

friend.complete_attribute = 'complete'. Then we include a code

block that sets friend[i].complete = True. This tells

docassemble that an item friend[i] is not fully gathered until

friend[i].complete is defined. Thus, before docassemble moves

on to the next item in a list, it will run this code block to

completion. This code block will cause other attributes of

friend[i] to be defined, including .birthdate and

.favorite_animal. Here is what the revised interview looks like:

objects:

- friend: |

DAList.using(

object_type=Individual,

complete_attribute='complete',

there_are_any=True)

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Your friends

subquestion: |

% for x in friend:

* ${ x } likes

${ noun_plural(x.favorite_animal).lower() }

and is

${ x.age_in_years() }

years old.

% endfor

---

code: |

friend[i].name.first

friend[i].birthdate

friend[i].favorite_animal

friend[i].complete = True

---

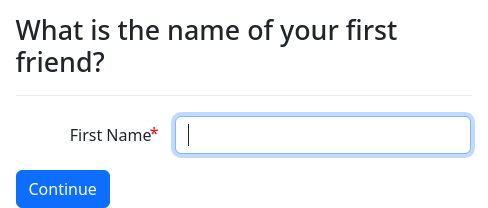

question: |

What is the name of your ${ ordinal(i) }

friend?

fields:

- First Name: friend[i].name.first

---

question: |

What is

${ friend[i].possessive('birthdate') }?

fields:

- Birthdate: friend[i].birthdate

datatype: date

---

question: |

What is

${ friend[i].possessive('favorite animal') }?

fields:

- Favorite animal: friend[i].favorite_animal

---

question: |

Do you have any other friends?

yesno: friend.there_is_anotherNow the order of questions is:

- What is the name of your first friend?

- What is Fred’s birthdate?

- What is Fred’s favorite animal?

- Do you have any other friends?

- What is the name of your second friend?

- What is Sally’s birthdate?

- What is Sally’s favorite animal?

- Do you have any other friends?

You can use any attribute you want as the complete_attribute.

Defining a complete_attribute simply means that instead of ensuring

that a list item is displayable (i.e., gathering the name of an

Individual), docassemble will seek a definition of the attribute

indicated by complete_attribute. If .birthdate was the only

element we wanted to define during the gathering process, we could

have written friend.complete_attribute = 'birthdate' and skipped the

code block entirely.

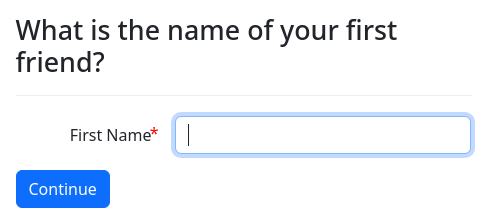

You can also set complete_attribute to a list of attribute names. In

this case, the item will be considered complete when it has a

definition for each attribute in the list of of attributes.

objects:

- friend: |

DAList.using(

object_type=Individual,

complete_attribute=['name.first', 'birthdate', 'favorite_animal'],

there_are_any=True)

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Your friends

subquestion: |

% for x in friend:

* ${ x } likes

${ noun_plural(x.favorite_animal).lower() }

and is

${ x.age_in_years() }

years old.

% endfor

---

question: |

What is the name of your ${ ordinal(i) }

friend?

fields:

- First Name: friend[i].name.first

---

question: |

What is

${ friend[i].possessive('birthdate') }?

fields:

- Birthdate: friend[i].birthdate

datatype: date

---

question: |

What is

${ friend[i].possessive('favorite animal') }?

fields:

- Favorite animal: friend[i].favorite_animal

---

question: |

Do you have any other friends?

yesno: friend.there_is_anotherIt is a best practice to set complete_attribute='complete' and to

specify a code block that sets the .complete attribute of the list

item to True. This will facilitate the use of a table for editing

the list. Every time the user edits a list item in a table, the

.complete attribute will be undefined if complete_attribute is

'complete', and then the definition of .complete will be sought

again. Thus the “completeness” of the list item will always be

recomputed if the user changes something.

When you write your own class definitions, you can set a

default complete_attribute that is not really an attribute, but a method

that behaves like an attribute.

In the following example, FishList is a list of Fish, where a

Fish is considered “complete” for purposes of auto-gathering when

the common_name, scales, and species attributes have been

defined.

from docassemble.base.util import DAList, DAObject

__all__ = ['FishList', 'Fish']

class FishList(DAList):

def init(self, *pargs, **kwargs):

self.object_type = Fish

self.complete_attribute = 'fish_complete'

super().init(*pargs, **kwargs)

class Fish(DAObject):

@property

def fish_complete(self):

self.common_name

self.scales

self.species

def __str__(self):

return self.common_nameHere is an interview that uses this class definition.

modules:

- .fishlist

---

objects:

- fishes: FishList

---

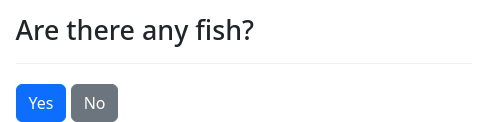

question: |

Are there any fish?

yesno: fishes.there_are_any

---

question: |

Are there any more fish?

yesno: fishes.there_is_another

---

question: |

What is the ${ ordinal(i) } fish's common name?

fields:

- Name: fishes[i].common_name

---

question: |

Tell me more about the ${ fishes[i] }.

fields:

- Species name: fishes[i].species

- Number of scales: fishes[i].scales

datatype: integer

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Thank you for telling me about ${ fishes }.Gathering lists within lists

Here is an example of gathering nested lists (a list within a list within a list).

objects:

- person: |

DAList.using(

object_type=Individual,

minimum_number=1,

complete_attribute='complete')

- person[i].child: |

DAList.using(

object_type=Individual,

complete_attribute='complete')

---

code: |

person[i].name.first

person[i].name.last

person[i].allergy.gather()

person[i].child.gather()

person[i].complete = True

---

code: |

person[i].child[j].name.first

person[i].child[j].name.last

person[i].child[j].allergy.gather()

person[i].child[j].complete = True

---

question: |

What is the name of the

${ ordinal(i) }

person?

fields:

- First: person[i].name.first

- Last: person[i].name.last

---

question: |

Is there another person?

yesno: person.there_is_another

---

question: |

Does ${ person[i] } have any children?

yesno: person[i].child.there_are_any

---

question: |

What is the name of

${ person[i].possessive(ordinal(j) + ' child') }?

fields:

- First: person[i].child[j].name.first

- Last: person[i].child[j].name.last

---

question: |

Does ${ person[i] } have any

children other than ${ person[i].child }?

yesno: person[i].child.there_is_another

---

generic object: Individual

objects:

- x.allergy: DAList

---

generic object: Individual

question: |

Does ${ x } have any allergies?

yesno: x.allergy.there_are_any

---

generic object: Individual

question: |

What allergy does ${ x } have?

fields:

- Allergy: x.allergy[i]

---

generic object: Individual

question: |

Does ${ x } have any allergies

other than ${ x.allergy }?

yesno: x.allergy.there_is_another

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Information retrieved

subquestion: |

You told me about

${ person.quantity_noun('individual') },

their allergies, their children,

and their children's allergies.

% for p in person:

You told me about ${ p }.

% if p.allergy.number() > 0:

${ p } is allergic to ${ p.allergy }.

% endif

% for c in p.child:

${ p } has a child named ${ c }.

% if c.allergy.number() > 0:

${ c } is allergic to ${ c.allergy }.

% endif

% endfor

% endforThe first block defines the objects we will use.

objects:

- person: |

DAList.using(

object_type=Individual,

minimum_number=1,

complete_attribute='complete')

- person[i].child: |

DAList.using(

object_type=Individual,

complete_attribute='complete')(Note that the line breaks here are not meaningful to the syntax; Python allows you to use line breaks in this context for aesthetic reasons.)

The list person will be a list of objects of type Individual.

We assume that there is at least one individual in the list, so we set

minimum_number=1. Since we want to gather more information about

each individual in the list than simply the individual’s name (the

textual representation of an Individual), we set

complete_attribute='complete' to indicate that an individual is not

“complete” until the attribute .complete is defined.

We also assert here that the attribute child for any given person in

the list of people (person[i].child) is a list of Individuals,

each of which will be “complete” when the .complete attribute is

defined. The variable i here is a special variable that is set by

docassemble during the list gathering process. (You should never

try to set i yourself.) If docassemble wants the definition of

person[0].child, it will set i = 0 and then define

person[0].child by running the second line in the objects block.

The next block specifies what it means for an Individual item in

the person list to be “complete.”

code: |

person[i].name.first

person[i].name.last

person[i].allergy.gather()

person[i].child.gather()

person[i].complete = TrueThis says that a given Individual in the person list

(person[i]) is “complete” when the person’s name is defined, when we

have gathered a list of the person;s allergies, and when we have

gathered a list of their children.

We have seen the block that defines person[i].child for any i.

Later on we will see the block that defines person[i].allergy.

When docassemble wants to make a person[0] “complete,” it will

set i = 0 and then run this Python code block. It will keep

running this block until it gets the answers it needs. First it will

ask for the person’s name, then it will go through a list gathering

process to gather the allergies, and then go through a list gathering

process to gather the children, and when there are no more children to

gather, it will define the complete attribute by setting it to

True. Then the person[i] will be “complete,” and docassemble

will continue gathering the person list.

The next block defines what it means for a child of a given

person[i] to be complete. It is similar to the previous block,

except the interview doesn’t ask about a child’s children.

code: |

person[i].child[j].name.first

person[i].child[j].name.last

person[i].child[j].allergy.gather()

person[i].child[j].complete = TrueWhile docassemble is running person[i].child.gather(), it will

ask questions to gather the items in person[i].child and to make

each item, such as person[0].child[1] (for the first person’s second

child) “complete.” Since the child attribute is defined with

complete_attribute='complete', docassemble will try to make

person[0].child[1] “complete” by seeking a definition of

person[0].child[1].complete. There is no block in the interview

that offers to define person[0].child[1].complete specifically, but

the code block above offers to define

person[i].child[j].complete for any arbitrary i and j. So

docassemble will set i = 0 and j = 1, and then try running

this code block. The Python code in this block will trigger all

the necessary questions to make the child object “complete.”

It is very important that the code in this code block is in a

separate block from the previous code block. Each code block

represents a separate statement of truth. The first code block

says what it takes to be finished asking questions about a

person[i], and the second code block says what it takes to be

finished asking questions about one of that person’s children.

If you tried to merge this code with the code from the previous block,

then you might get an error about the variable j being undefined.

If docassemble is looking to define an attribute of person[i],

it will define i and then run the block that offers to define the

attribute of person[i]. But if docassemble, in the course of

running a block that defines the attribute of person[i], encounters

the variable j, it will not know what to do with that; it didn’t set

j to anything before running the code block, so j will be

undefined.

While Python is a “procedural” language, the way docassemble

works is more “declarative.” In most cases, your code blocks should

be self-contained declarations about how a single variable should be

defined, even if they cause other variables to be defined as a side

effect. In this example, those single variables are

person[i].complete and person[i].child[j].complete. The blocks

that define these variables will be called upon at multiple times in

your interview for the specific purpose of defining

person[i].complete or person[i].child[j].complete.

The next block is a reusable question.

question: |

What is the name of the

${ ordinal(i) }

person?

fields:

- First: person[i].name.first

- Last: person[i].name.lastThis question will be used for person[0], person[1], and any

other person[i] in the person list. If docassemble wants to

know person[1].name.first, it will set i = 1 and then ask this

question.

The next block is used whenever docassemble wants to know whether there are more items to be added to a list.

question: |

Is there another person?

yesno: person.there_is_anotherThe .gather() method of the DAList class will undefine the

.there_is_another attribute after each item is gathered, and then

re-seek a definition of .there_is_another to figure out if more

items need to be gathered.

The next block asks whether a person in the person list has any

children.

question: |

Does ${ person[i] } have any children?

yesno: person[i].child.there_are_anyThis is the first question that will be asked when docassemble

runs person[i].child.gather().

The next question illustrates the use of two index variables.

question: |

What is the name of

${ person[i].possessive(ordinal(j) + ' child') }?

fields:

- First: person[i].child[j].name.first

- Last: person[i].child[j].name.lastThe use of the index variables i and j mean that if

docassemble wants to find a definition for

person[1].child[2].name.first, it will set i = 1, set j = 2, and

then ask this question.

If you wanted to ask the question a different way for the first person in the list, you could include the following block:

question: |

What is the name of the first person's

${ ordinal(j) } child?

fields:

- First: person[0].child[i].name.first

- Last: person[0].child[i].name.lastHere, the index variable i is used instead of j. docassemble

will only try to ask this question if the variable it seeks begins

with person[0].child. If docassemble is looking to define

person[1].child[0].name.first, it will disregard this question,

because person[0].child[i].name.first doesn’t generalize to

person[1].child[0].name.first.

Likewise, if you wanted to ask the question a different way for the first child, you could include:

question: |

What is the name of

${ person[i].possessive(ordinal(j) + ' first born child') }?

fields:

- First: person[i].child[0].name.first

- Last: person[i].child[0].name.lastThis question offers to define person[i].child[0].name.first for any

i.

You would never have a block that mentions j without also

mentioning i, and you would never have a block that mentions k

without also mentioning j and i. The variable i needs to be

used for the first index variable that is generalizable, and j needs

to be used for the second index variable that is generalizable.

Next is the block that asks whether a person has any more children.

question: |

Does ${ person[i] } have any

children other than ${ person[i].child }?

yesno: person[i].child.there_is_anotherNext we have a series of blocks relating to gathering the allergies of

people. These are similar in functionality to other blocks in this

interview, but they are different because they use the generic

object modifier and the special variable x, which represents the

“generic” object.

generic object: Individual

objects:

- x.allergy: DAList

---

generic object: Individual

question: |

Does ${ x } have any allergies?

yesno: x.allergy.there_are_any

---

generic object: Individual

question: |

What allergy does ${ x } have?

fields:

- Allergy: x.allergy[i]

---

generic object: Individual

question: |

Does ${ x } have any allergies

other than ${ x.allergy }?

yesno: x.allergy.there_is_anotherThe variable x works in a similar way to the way that index

variables like i and j work. If docassemble wants to define

the attribute allergy for an object person[0], and the object is

of type Individual, it can run x = person[0] and then process the

x.allergy: DAList line of the objects block. Likewise, if

docassemble wants to define person[1].child[0].allergy[3], it can

set x = person[1].child[0], set i = 3, and then ask the

question that defines x.allergy[i]. By using the generic

object feature, we save ourselves the trouble of writing separate

questions for gathering the allergies of person[i] and

person[i].child[j].

Finally, we have the single mandatory block of the interview,

which presents to the user all of the information that was gathered

during the interview.

mandatory: True

question: |

Information retrieved

subquestion: |

You told me about

${ person.quantity_noun('individual') },

their allergies, their children,

and their children's allergies.

% for p in person:

You told me about ${ p }.

% if p.allergy.number() > 0:

${ p } is allergic to ${ p.allergy }.

% endif

% for c in p.child:

${ p } has a child named ${ c }.

% if c.allergy.number() > 0:

${ c } is allergic to ${ c.allergy }.

% endif

% endfor

% endforAll of the questions that are asked during the interview are triggered

by the line % for p in person:. In order to iterate through

person, person first needs to be defined. That triggers the use

of the first objects block to define person. Then person

needs to be gathered, because you can’t iterate through a list that

hasn’t been gathered yet. That causes docassemble to gather the

items in person and to make them “complete.” Before any given

person[i] can be “complete,” the person’s name needs to be

collected, the allergies need to be gathered, and the children need to

be gathered. Before a child can be “complete,” the child’s

allergies need to be gathered. All of these questions are triggered

because each time the screen loads, docassemble tries to show the

mandatory question, and each time, it keeps encountering % for p in

person:.

Once person is gathered, the “for” loops all have enough

information, so no further questions needs to be asked.

Note that while the % for, % endfor, % if, and % endif lines

are indented when nested, the actual lines of text are not indented.

This is because indentation in Markdown has a special meaning (in

particular, to indicate that text should be formatted with a

fixed-width font). The indentation of % for, % endfor, % if,

and % endif is not necessary, but it helps make the code more readable.

Note that the line ${ c } is allergic to ${ c.allergy } makes use of

the fact that the textual representation of a DAList is the result

of running the comma_and_list() method on the list. So the

resulting sentence might be “Jane Doe is allergic to shellfish,

peanuts, and dust.”

Mixed object types

If you want to gather a list of objects that are not all the same

object type, you can do so by setting the .ask_object_type attribute

of the list to True providing a block that defines the

.new_object_type attribute of the list.

objects:

- location: |

DAList.using(

there_are_any=True,

ask_object_type=True)

---

mandatory: True

question: |

The locations

subquestion: |

% for loc in location:

* ${ loc }

% endfor

---

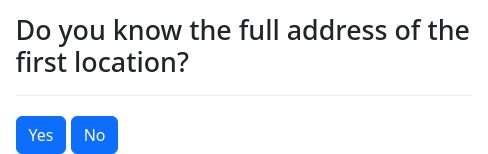

question: |

Do you know the full address of the

${ ordinal(location.current_index()) }

location?

buttons:

- Yes:

code: |

location.new_object_type = Address

- No:

code: |

location.new_object_type = City

---

question: |

What is the address of the

${ ordinal(i) } location?

fields:

- Address: location[i].address

- Unit: location[i].unit

required: False

- City: location[i].city

- State: location[i].state

code: |

states_list()

- Zip: location[i].zip

required: False

---

question: |

What is the city of the

${ ordinal(i) } location?

fields:

- City: location[i].city

- State: location[i].state

code: |

states_list()

---

question: |

Would you like to add another location?

yesno: location.there_is_anotherIn this example, we have a list called location, which is a type of

DAList. We have a mandatory code block that

sets location.ask_object_type to True. This instructs

docassemble that location is a list of objects, and that when a

new item is added to the list, docassemble should to look for the

value of location.new_object_type to figure out what type of object

the new item should be. By contrast, the .object_type attribute

instructs docassemble that the object type for every new object

should be the value of .object_type.

Thus, before docassemble adds a new item to the list, it will seek

a definition of location.new_object_type and then the item it adds

to the list will be an object of the type indicated by the value of

location.new_object_type. After each item is added, docassemble

forgets about the value of location.new_object_type, so the

question will be asked again for each item in the list.

There are a few things to note about the question that defines

location.new_object_type.

question: |

Do you know the full address of the

${ ordinal(location.current_index()) }

location?

buttons:

- Yes:

code: |

location.new_object_type = Address

- No:

code: |

location.new_object_type = CityThis a question about an item in a list, but note that we do not have

a variable i to indicate which item it is, since .new_object_type

is an attribute of the list location, not an attribute of the new

object (location[i]). Thus, we have to use the

.current_index() method to obtain the number.

Note also that we are using the method of

embedding a code block within a multiple choice question in order to

set the value of location.new_object_type based on user input. You

might think it would be simpler to just write the following:

question: |

Do you know the full address of the

${ ordinal(location.current_index()) }

location?

field: location.new_object_type

buttons:

- Yes: Address

- No: CityHowever, this would set location.new_object_type to a piece of text

('Address' or 'City'), instead of the object type (Address or

City). Thus, when setting .new_object_type (or .object_type),

make sure to use Python code.

If you don’t want to use a buttons interface, you can use code such

as the following to set the .new_object_type attribute to a Python

class.

question: |

Do you know the full address of the

${ ordinal(location.current_index()) }

location?

fields:

- Type: location.new_object_type_selection

choices:

- I know the full address

- I only know the city

---

code: |

if location.new_object_type_selection == 'I know the full address':

location.new_object_type = Address

else:

location.new_object_type = City

del location.new_object_type_selectionRunning del location.new_object_type_selection causes

location.new_object_type_selection to be undefined. This ensures that

the next time location.new_object_type is sought, the question will

be asked again.

Note that there are two questions that ask about attributes of the list items:

---

question: |

What is the address of the

${ ordinal(i) } location?

fields:

- Address: location[i].address

- Unit: location[i].unit

required: False

- City: location[i].city

- State: location[i].state

code: |

states_list()

- Zip: location[i].zip

required: False

---

question: |

What is the city of the

${ ordinal(i) } location?

fields:

- City: location[i].city

- State: location[i].state

code: |

states_list()

---You might be wondering how docassemble knows which of these two

questions to ask for a given item in the location list. If the

object is a City, a textual representation of the object will first

ask for .city and then .state. If the object is an Address, a

textual representation of the object will first ask for .address.

When docassemble gathers items into a list, it asks whatever

questions are necessary to construct a textual representation of the

item. So if the attribute docassemble needs is .city, both

questions are capable of defining that attribute. The “What is the

city” question comes last in the YAML file, so it takes precedence

over the “What is the address” question, and it will be asked. If the

attribute docassemble needs is .address, only the “What is the

address” question is capable of defining that, so only that question

will be asked.

If you set .ask_object_type to True and you want docassemble

to query for the .new_object_type, you need to trigger the list

gathering process by directly or indirectly calling .gather() on the

list. If you try to bypass the list gathering process, you may

encounter problems. For example, this will result in an error:

objects:

- mylist: DAlist.using(ask_object_type=True, there_are_any=True)

---

mandatory: True

code: |

mylist[0].favorite_fruitInstead, make sure the interview logic triggers the list gathering process. For example:

objects:

- mylist: DAlist.using(ask_object_type=True, there_are_any=True)

---

mandatory: True

code: |

for item in mylist:

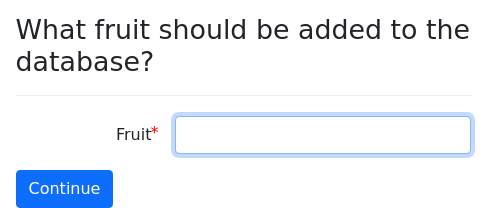

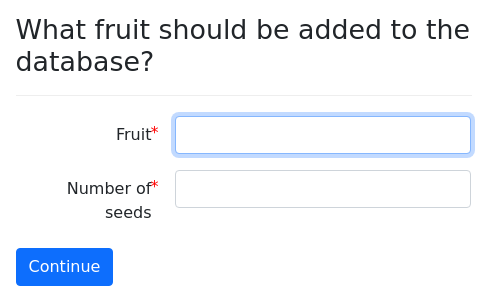

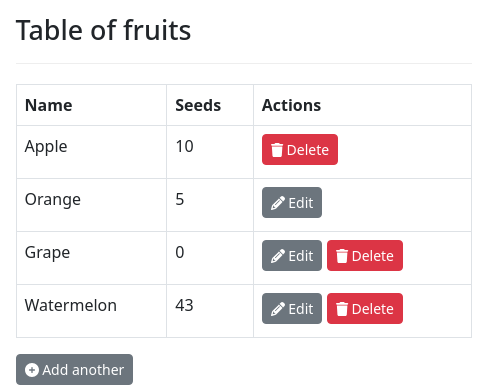

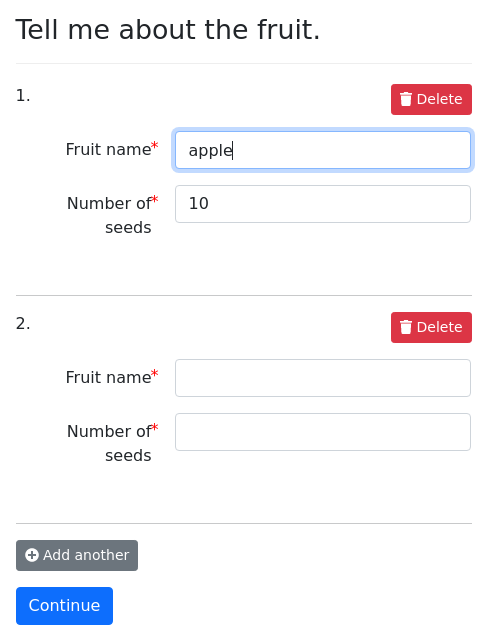

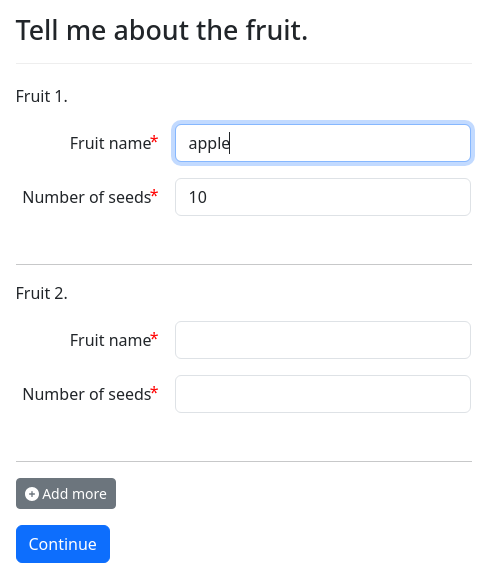

item.favorite_fruitGathering information into dictionaries

The process of gathering the items in a DADict dictionary is

slightly different from the process of gathering the items of a

DAList. Like the gathering process for DAList objects, the

gathering process for DADict objects will call upon the attributes

.there_are_any and .there_is_another.

In addition, the process will look for the attribute .new_item_name

to get the key to be added to the dictionary. In the example below,

we build a DADict in which the keys are the names of fruits and

the values are the number of seeds that fruit contains. There is one

question that asks for the fruit name (fruit.new_item_name) and a

separate question that asks for the number of seeds (fruit[i]).

(When populating a DADict, i refers to the key, whereas when

populating a DAList, i refers to a number like 0, 1, 2, etc.)

objects:

- fruit: DADict

---

mandatory: True

question: |

There

${ fruit.does_verb("is") }

${ fruit.number_as_word() }

fruits in all.

subquestion: |

% for item in fruit:

The fruit ${ item } has

${ fruit[item] } seeds.

% endfor

---

code: |

fruit.there_are_any = True

---

question: |

What fruit should be added to

the database?

fields:

- Fruit: fruit.new_item_name

---

question: |

How many seeds does

${ indefinite_article(noun_singular(i)) }

have?

fields:

- Number of seeds: fruit[i]

datatype: integer

min: 0

---

question: |

So far, the fruits in the database

include ${ fruit }. Are there

any others?

yesno: fruit.there_is_anotherAlternatively, you can use the attribute .new_item_value to set the

value of a new item.

objects:

- fruit: DADict

---

mandatory: True

question: |

There are ${ fruit.number_as_word() }

fruits in all.

subquestion: |

% for item in fruit:

The fruit ${ item } has

${ fruit[item] } seeds.

% endfor

---

code: |

fruit.there_are_any = True

---

question: |

What fruit should be added to

the database?

fields:

- Fruit: fruit.new_item_name

- Number of seeds: fruit.new_item_value

datatype: integer

min: 0

---

question: |

So far, the fruits in the database

include ${ fruit }. Are there

any others?

yesno: fruit.there_is_anotherThe value of the .new_item_value attribute will never be sought by

the gathering process; only the value of the

.new_item_name attribute will be sought. So if you want to use

.new_item_value, you need to set it using a question that

simultaneously sets .new_item_name, as in the example above.

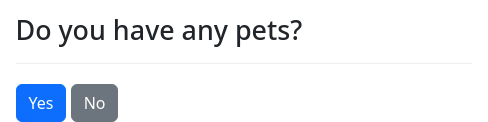

Gathering a dictionary of objects

You can also populate the contents of a DADict in which each value

is itself an object.

objects:

- pet: DADict.using(object_type=DAObject)

---

mandatory: True

question: |

You have ${ pet.number_as_word() }

pets.

subquestion: |

% for item in pet:

Your pet ${ item } named

${ pet[item].name } has

${ pet[item].feet } feet.

% endfor

---

question: |

Do you have any pets?

yesno: pet.there_are_any

---

question: |

What kind of pet do you have?

fields:

- Type of pet: pet.new_item_name

---

question: |

Describe your pet ${ i }.

fields:

- Name: pet[i].name

- Number of feet: pet[i].feet

datatype: integer

min: 0

---

question: |

So far, you have told me about your

${ pet }. Do you have any other

pets?

yesno: pet.there_is_anotherIn the example above, we populate a DADict called pet, in which

the keys are a type of pet (e.g., 'cat', 'dog'), and the values

are objects of type DAObject with attributes .name (e.g.,

'Mittens', 'Spot') and .feet (e.g., 4). We need to start by

telling docassemble that the DADict is a dictionary of

objects. We do this by setting the .object_type attribute of the

DADict to DAObject. Then we provide a question that sets the

.new_item_name attribute.

When a .object_type is provided, docassemble will take care of

initializing the value of each entry as an object of this type. It

will also automatically gather whatever attributes, if any, are

necessary to represent the object as text. The representation of the

object as text is what you see if you include the object in a Mako template:

${ pet['cat'] }. (Or, if you know Python, it is the result of

str(pet['cat']).) The attributes necessary to represent the object

as text depend on the type of object. In the case of a DAObject,

no attributes are required to represent the object as text. In the

case of an Individual, the individual’s name is required

(.name.first at a minimum).

Since a DAObject does not have any necessary attributes, then in

the example above, the pet object is considered “gathered”

(i.e. pet.gathered is True) after all the types of pet (e.g.,

'cat', 'dog') have been provided. At this point, the values of

the DADict are simply empty DAObjects. The .name and

.feet attributes are still not defined. The final screen of the

interview, which contains a “for” loop that describes the number of

feet of each pet, causes the asking of questions to obtain the .feet

and .name attributes.

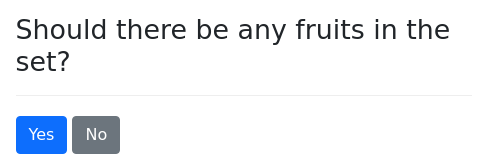

Gathering information into sets

The gathering of items into a DASet is much like the gathering of

items into a DADict. The difference is that instead of using the

attributes .new_item_name and .new_item_value, you use a single

attribute, .new_item.

Here is an example that gathers a set of text items (e.g., 'apple',

'orange', 'banana') into a DASet.

objects:

- fruit: DASet

---

mandatory: True

question: |

There are ${ fruit.number_as_word() }

fruits in all.

subquestion: |

The fruit include ${ fruit }.

---

question: |

Should there be any fruits

in the set?

yesno: fruit.there_are_any

---

question: |

What fruit should be added to

the set?

fields:

- Fruit: fruit.new_item

---

question: |

So far, the fruits in the set

include ${ fruit }. Are there

any others?

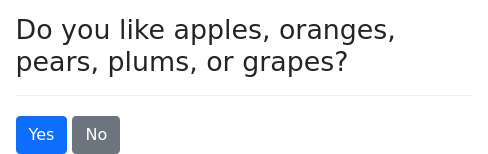

yesno: fruit.there_is_anotherYou can also gather objects into a DASet. However, the DASet

does not use the .object_type attribute, as DAList and

DADict groups do. The objects that you gather into a DASet

need to exist already.

In the example below, we create several DAObjects, each

representing a fruit, and we use a multiple choice question with

datatype set to object to ask which fruits the user likes. (See

selecting objects for more information about these types of

questions.)

objects:

- fruit: DASet

- my_favorites: DASet

- apple: DAObject

- orange: DAObject

- pear: DAObject

- plum: DAObject

- grape: DAObject

---

mandatory: True

code: |

apple.name = "apples"

orange.name = "oranges"

pear.name = "pears"

plum.name = "plums"

grape.name = "grapes"

my_favorites.add(apple, pear)

my_favorites.gathered = True

---

mandatory: True

question: |

There are ${ fruit.number_as_word() }

fruits in all.

subquestion: |

% if fruit.number():

The fruits you like include ${ fruit }.

% endif

% if fruits_in_common.number():

The fruits we both like are

${ fruits_in_common }.

% endif

---

code: |

fruits_in_common = fruit.intersection(my_favorites)

---

question: |

Do you like ${ apple }, ${ orange },

${ pear }, ${ plum }, or ${ grape }?

yesno: fruit.there_are_any

---

question: |

Pick a fruit that you like.

fields:

- Fruit: fruit.new_item

datatype: object

choices:

- apple

- orange

- pear

- plum

- grape

---

question: |

So far, you have indicated you like

${ fruit }. Are there any other

fruits you like?

yesno: fruit.there_is_anotherManually triggering the gathering process

In the examples above, the process of asking questions that populate

the list is triggered implicitly by code like ${ fruit.number() },

${ fruit } or % for item in fruit:.

If you want to ask the questions at a particular time, you can do so

by referring to fruit.gather(). (Behind the scenes, this is the

same method used when the process is implicitly triggered.)

mandatory: True

code: |

fruit.gather(minimum=1)

---

question: |

What fruit should be added to the list?

fields:

- Fruit: fruit[i]

---

question: |

So far, the fruits include

${ fruit }. Are there any others?

yesno: fruit.there_is_another

---

mandatory: True

question: |

The fruits are ${ fruit }.The .gather() method accepts some optional keyword arguments:

minimumcan be set to the minimum number of items you want to gather. The.there_are_anyattribute will not be sought. The.there_is_anotherattribute will be sought after this minimum number is reached.numbercan be set to the total number of items you want to gather. The.there_is_anotherattribute will not be sought.item_object_typecan be set to the type of object each element of the group should be. (This is not available forDASetobjects.)complete_attributecan be set to the name of an attribute that should be sought for each item during the gathering process. You can also set thecomplete_attributeattribute of the group object itself.

The .gather() method is not the only way that a gathering process

can be triggered. The .auto_gather attribute controls whether the

.gather() method is invoked. If .auto_gather is True (which is

the default), then the gathering process will be triggered using

.gather(). If .auto_gather is False, the gathering process will

be triggered in a simpler way: by seeking the value of .gathered.

Thus, you can provide a code block that sets .gathered to

True. For example:

code: |

fruit.append('apple', 'orange', 'grape')

fruit.gathered = True

---

mandatory: True

code: |

fruit.auto_gather = False

---

mandatory: True

question: |

The fruits are ${ fruit }.Setting .gathered to True means that when you try to get the

length of the group or iterate through it, docassemble will assume

that nothing more needs to be done to populate the items in the group.

You can still add more items to the list if you want to, using

code blocks.

Detailed explanation of gathering process

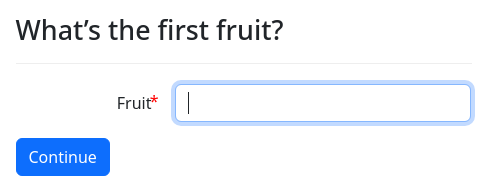

At a very basic level, it is not complicated to gather a list of things from a user. For example, you can do this:

objects:

- fruit: DAList

---

question: |

How many fruits are there?

fields:

- Number: number_of_fruits

datatype: integer

min: 2

---

question: |

What's the ${ ordinal(i) } fruit?

fields:

- Fruit: fruit[i]

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Fruits

subquestion: |

The fruits are:

% for index in range(0, number_of_fruits):

* ${ fruit[index] }

% endforThis example uses Python’s built-in range() function, which

returns a list of integers starting with the first argument and less

than the second argument. For example:

>>> range(0, 5)

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4]The for loop iterates through all the numbers using the variable

index, looking for fruit[index]. The first item it looks for is

fruit[0]. Since this is not defined yet, the interview looks for a

question that offers to define fruit[0]. It does not find any

questions that define fruit[0], so it then looks for a question that

offers to defined fruit[i]. It finds this question, and asks it of

the user. After the user provides an answer, the for loop runs

again. This time, fruit[0] is already defined. But on the next

iteration of the for loop, the interview looks for fruit[1] and

finds it is not defined. So the interview repeats the process with

fruit[1]. When all of the fruit[index] are defined, the

mandatory question is able to be shown to the user, and the

interview ends.

Another way to ask questions is to ask for one item at a time, and after each item, ask if any additional items exist.

objects:

- fruit: |

DAList.using(

auto_gather=False,

gathered=True)

comment: |

These attributes disable the automatic

gathering system.

---

mandatory: True

code: |

num_fruits = 0

more_fruits = True

---

mandatory: True

code: |

while more_fruits:

fruit[num_fruits]

num_fruits += 1

del more_fruits

---

question: |

Are there more fruits?

yesno: more_fruits

---

question: |

What's the ${ ordinal(i) } fruit?

fields:

- Fruit: fruit[i]

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Fruits

subquestion: |

The fruits are:

% for item in fruit:

* ${ item }

% endforTo gather the list manually, it is necessary to disable the automatic gathering system:

objects:

- fruit: |

DAList.using(

auto_gather=False,

gathered=True)This example uses a little bit of Python code to ask the appropriate questions.

Some variables are initialized:

num_fruits = 0

more_fruits = TrueThen the main algorithm is:

while more_fruits:

fruit[num_fruits]

num_fruits += 1

del more_fruitsSince more_fruits is initialized as 0, the first undefined

variable that this code encounters is fruit[0]. When the code

encounters fruit[0], it will go looking for the value of fruit[0],

and the question “What’s the first fruit?” will be asked. Once

fruit[0] is defined, the interview undefines more_fruits, but then

when the while loop loops around, the definition of more_fruits is

needed. Since more_fruits is undefined, the interview presents the

user with the more_fruit question, which asks “Are there more

fruits?” If more_fruits is True, the loop repeats, and the

definition of fruit[1] is sought.

This is starting to get complicated. And things get even more complicated when you want to say things like “There are three fruits in all” and “You have told me about three fruits so far” in your interview questions. In the case of “There are three fruits in all,” a prerequisite to saying this is to make sure that the user has supplied the full list. But in the case of “You have told me about three fruits so far,” you would not want this prerequisite.

Since asking users for lists of things can get complicated, docassemble has a feature for automating the process of asking the necessary questions to fully populate the list.

If your list is fruit, there are three special attributes:

fruit.gathered, fruit.there_are_any, and fruit.there_is_another.

The fruit.gathered attribute is initially undefined, but is set to

True when the list is completely populated. The

fruit.there_are_any attribute is used to ask the user whether the

list is empty. The fruit.there_is_another attribute is used to ask

the user questions like “You have told me about three fruits so far:

apples, peaches, and pears. Are there any additional fruits?”

In addition to these two attributes, there is special method,

fruit.gather(), which will cause appropriate questions to be asked

and will return True when the list has been fully populated. The

.gather() method looks for definitions for fruit.there_are any,

fruit[i], and fruit.there_is_another. It makes

fruit.there_is_another undefined as necessary.

Here is a complete example:

objects:

- fruit: DAList

---

mandatory: True

question: |

There are ${ fruit.number_as_word() }

fruits in all.

subquestion: |

The fruits are ${ fruit }.

---

question: |

Are there any fruit that you would like

to add to the list?

yesno: fruit.there_are_any

---

question: |

What fruit should be added to the list?

fields:

- Fruit: fruit[i]

---

question: |

So far, the fruits include ${ fruit }.

Are there any others?

yesno: fruit.there_is_anotherAvoiding triggering the gathering process

docassemble implicitly calls .gather() in many circumstances,

such as when you do for item in my_list:, len(my_list), or

my_dict.items(). In some situations, you may want to use a DAList,

DADict, or DASet while the gathering process is still going on, or

has not been started yet.

To test whether a group has been gathered, you can call

.has_been_gathered() on it. This will return True if the group

has been gathered, and False otherwise.

To test whether the gathering process has been started, you can access

the .gathering_started attribute.

To get the number of items in a group without triggering the gathering

process, call .number_gathered(). This will return the number of

items gathered so far.

To sort a group even if it has not been fully gathered yet, call

.sort_elements() instead of .sort().

The DAList, DADict, and DASet objects have an attribute

.elements that is a plain Python list, dict, or set containing

the items in the group. To bypass the special features of DAList,

DADict, and DASet, you can access .elements directly, and the

list gathering process will not be triggered.

When the gathering process is still going on and your group contains

objects, .elements may contain one or more items that are not

usable. For example, when the interview is in the process of asking

for the fifth item in the group, you may want to show the user the

first four items. However, if you try to loop over .elements and

display information about each one, you may find yourself in a

Catch-22 because your code expects attributes of the fifth item to be

defined when those attributes are defined by the very same

question you are trying to ask. Instead of accessing .elements,

you can call .complete_elements(). This will return a DAList,

DADict, or DASet containing only elements that are “complete.”

Whether an item is “complete” depends on whether the group has a

complete_attribute. If the group has a complete_attribute, an

item in the group will be considered “complete” if the item has an

attribute by the name of the complete_attribute. If the group does

not have a complete_attribute, an item will be considered

“complete” if it can be reduced to text without encountering an

undefined variable. For example, an Individual object can be

reduced to text if the .name.first attribute is defined, so if a

DAList called my_list contains several Individual objects,

my_list.complete_elements() will return a DAList containing a

only those objects where .name.first is defined.

Using “for loops”

In computer programming, a “for loop” allows you to do something repeatedly, such as iterating through each item in a list.

For example, here is an example in Python:

numbers = [5, 7, 2]

total = 0

for n in numbers:

total = total + n

print totalThis code “loops” through the elements of numbers and computes the

total amount. At the end, 14 is printed.

For loops based on DAList, DADict, and DASet objects can

be included in textual content using the for/endfor Mako statement:

code: |

fruit_list = ['peaches', 'pears', 'apricots']

---

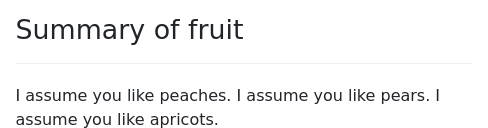

question: |

Summary of fruit

subquestion: |

% for fruit in fruit_list:

I assume you like ${ fruit }.

% endfor

mandatory: TrueMako “for” loops work just like Python for loops, except that they need to be ended with “endfor.”

If the list might be empty, you can check its length using an

if/else/endif Mako statement:

question: |

Summary of fruit

subquestion: |

% if len(fruit_list) > 0:

% for fruit in fruit_list:

I assume you like ${ fruit }.

% endfor

% else:

There are no fruits to discuss.

% endif

mandatory: TrueYou can also use the .number() method:

question: |

Summary of the case

subquestion: |

% if case.plaintiff.number() > 0:

% for person in case.plaintiff:

${ person } is a plaintiff.

% endfor

% else:

There are no plaintiffs.

% endifYou can check if something is in a list using a statement of the form

if … in:

---

question: |

% if client in case.plaintiff:

Since you are bringing the case, it will be your responsibility to

prove that you were harmed.

% else:

The responsibility to prove this case belongs to

${ case.plaintiff }. You do not have to testify in your defense.

% endif

---For more information about “for loops” in Mako, see the markup section.

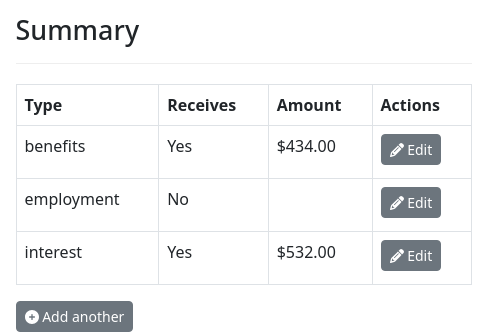

Edit an already-gathered list

It is possible to allow your users to edit a DAList list that has

already been gathered. Here is an example.

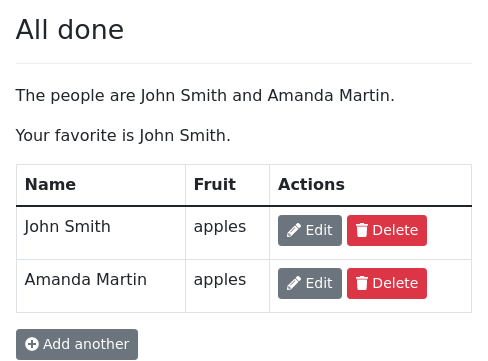

mandatory: True

question: |

All done

subquestion: |

The people are ${ person }.

Your favorite is ${ favorite }.

${ person.table }

${ person.add_action() }

---

table: person.table

rows: person

columns:

- Name: |

row_item.name.full()

- Fruit: |

row_item.favorite_fruit

edit:

- name.first

- favorite_fruitThis works using two features:

- The

editspecifier on thetableblock, which adds an “Actions” column to the table and indicates which screens should be shown when the user clicks the “Edit” button. First a screen will be shown that asks for the the attribute.name.first. Then a screen will be shown that asks for the attribute.favorite_fruit. - The

.add_action()method on theDAListinserts HTML for a button that the user can press in order to add an entry to an already-gathered list.

You can allow your users to edit a DAList from an edit button in a

review page.

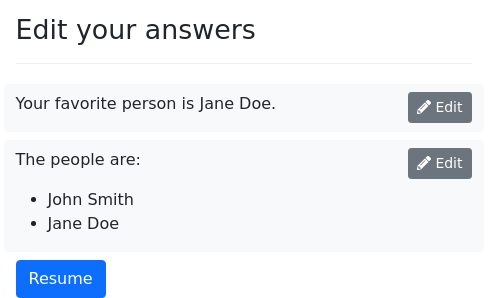

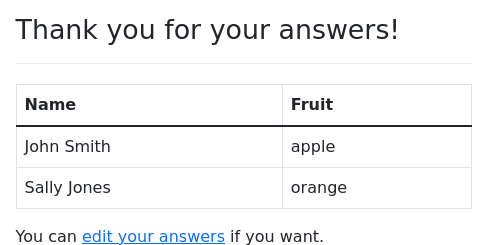

mandatory: true

question: |

Thank you for your answers!

subquestion: |

The people are ${ person } and your

favorite is ${ favorite }.

You can

[edit your answers](${ url_action('review_interview') })

if you want.

---

event: review_interview

question: |

Edit your answers

review:

- Edit: favorite

button: |

Your favorite person is ${ favorite }.

- Edit: person.revisit

button: |

The people are:

% for y in person:

* ${ y }

% endfor

---

continue button field: person.revisit

question: |

Edit the people

subquestion: |

${ person.table }

${ person.add_action() }

---

table: person.table

rows: person

columns:

- Name: |

row_item.name.full()

- Fruit: |

row_item.favorite_fruit

edit:

- name.first

- favorite_fruitThe attribute .revisit of a DAList is special; it is undefined

by default and is set to True by the auto-gathering process at the

same time that .gathered is set to True. Because .revisit is

undefined at first, the review block will not show the “Edit”

button for the list until the list is gathered. When the list has

been gathered, and the user clicks the “Edit” button associated with

.revisit, the user is taken to the block with continue button field:

person.revisit. On this screen, you can show the list as a table

and provide the .add_action() button if you want users to be able to

add entries.

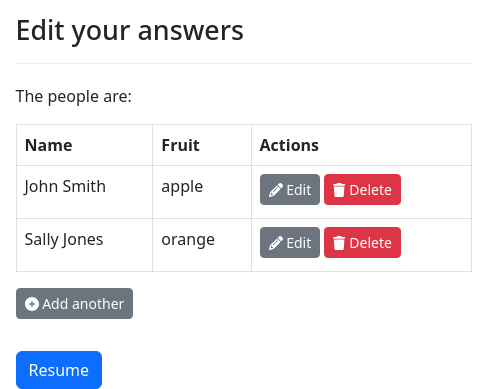

Putting an editable table directly into a review page is also possible.

need: person.table

mandatory: true

question: |

Thank you for your answers!

subquestion: |

The people are ${ person }.

You can

[edit your answers](${ url_action('review_interview') })

if you want.

---

event: review_interview

question: |

Edit your answers

review:

- note: |

% if len(person):

The people are:

${ person.table }

${ person.add_action() }

% else:

There are no people.

${ person.add_action("I would like to add one.") }

% endif

---

table: person.table

rows: person

columns:

- Name: |

row_item.name.full()

- Fruit: |

row_item.favorite_fruit

edit:

- name.first

- favorite_fruitThe line need: person.table is important here. An item in a

review list will not be shown if it contains any undefined

variables. The presence of an undefined variable in a review list

item will not cause docassemble to seek a definition of that

variable (unless the specifier skip undefined: False is used).

Therefore, if you want a review item containing a table to be

displayed, you need to make sure that the variable representing the

table gets defined by the time that you want the table to be

editable. In this example, need: person.table ensures that the

variable representing the table is defined before the user is given

the opportunity to review his or her answers.

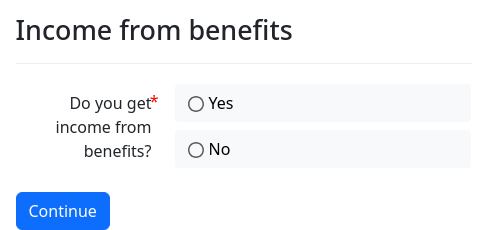

While the above examples have all featured tables for editing DAList

objects, the edit feature can also be used when the rows of the

table refer to a DADict:

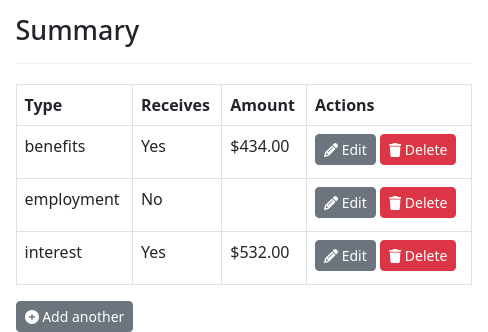

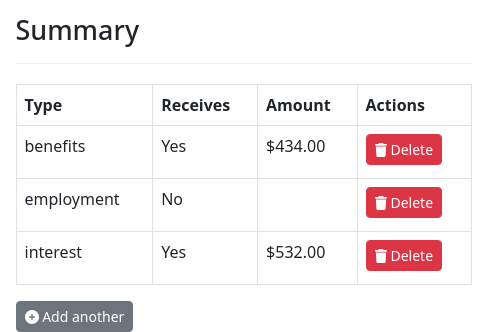

objects:

- income: |

DADict.using(

object_type=DAObject,

keys=['employment', 'benefits', 'interest'],

complete_attribute='complete',

there_is_another=False)

---

code: |

if income[i].receives:

income[i].amount

income[i].complete = True

---

question: |

Income from ${ i }

fields:

- "Do you get income from ${ i }?": income[i].receives

datatype: yesnoradio

- "How much do you get from ${ i }?": income[i].amount

datatype: currency

show if: income[i].receives

---

table: income.table

rows: income

columns:

- Type: |

row_index

- Receives: |

'Yes' if row_item.receives else 'No'

- Amount: |

currency(row_item.amount) if row_item.receives else ''

edit:

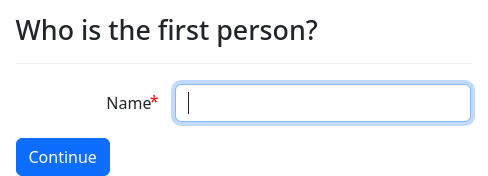

- receivesIf your DAList is not made up of objects, it can be made editable

by setting edit to True instead of to a list of attributes.

question: |

Who is the ${ ordinal(i) } person?

fields:

- Name: person[i]

---

question: |

Are there any more people

you would like to mention?

yesno: person.there_is_another

---

mandatory: True

question: |

All done

subquestion: |

The people are ${ person }.

${ person.table }

${ person.add_action() }

---

table: person.table

rows: person

columns:

- "#": |

row_index + 1

- Name: |

row_item

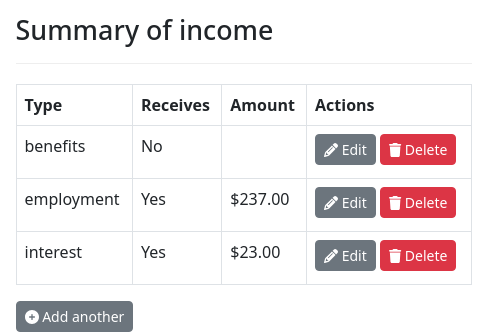

edit: TrueYou can do the same with DADict groups that do not use objects:

question: |

Income from ${ i }

fields:

- "How much income do you get from ${ i }?": income[i]

datatype: currency

---

question: |

What type of income would you

like to add?

fields:

- "Type of income": income.new_item_name

---

table: income.table

rows: income

columns:

- Type: |

row_index

- Receives: |

'Yes' if row_item > 0 else 'No'

- Amount: |

currency(row_item) if row_item > 0 else ''

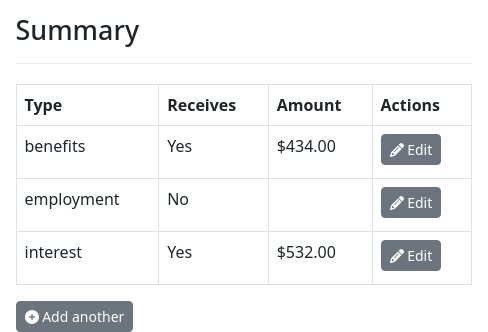

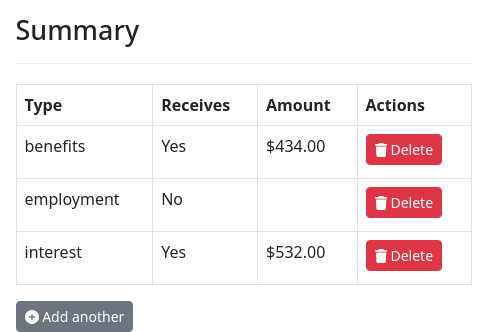

edit: TrueCustomizing the editing interface

If you do not want your users to be able to delete items, you can add

delete buttons: False to the table.

table: income.table

rows: income

columns:

- Type: |

row_index

- Receives: |

'Yes' if row_item.receives else 'No'

- Amount: |

currency(row_item.amount) if row_item.receives else ''

edit:

- receives

delete buttons: FalseOr, if you want your users to be able to delete items, but not edit

items, you can include delete buttons: True and do not include

edit:

table: income.table

rows: income

columns:

- Type: |

row_index

- Receives: |

'Yes' if row_item.receives else 'No'

- Amount: |

currency(row_item.amount) if row_item.receives else ''

delete buttons: TrueIf you want to allow your users to delete items, but only if the group

is longer than a certain length, you can give the DAList or

DADict a minimum_number attribute.

objects:

- income: |

DADict.using(

object_type=DAObject,

keys=['employment', 'benefits', 'interest'],

complete_attribute='complete',

minimum_number=3,

there_is_another=False)If you have a DAList or a DADict and you

want the user to confirm before deleting an item that they really

meant to delete the item, you can include confirm: True.

table: income.table

rows: income

columns:

- Type: |

row_index

- Receives: |

'Yes' if row_item.receives else 'No'

- Amount: |

currency(row_item.amount) if row_item.receives else ''

delete buttons: True

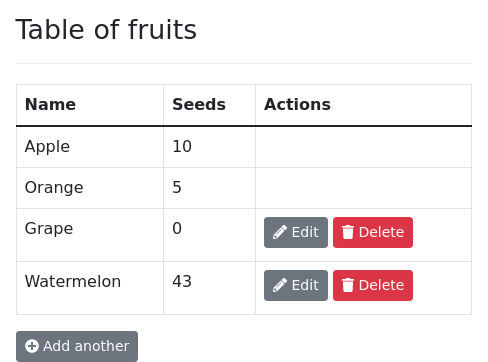

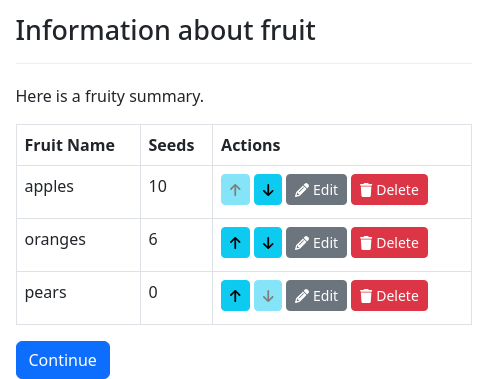

confirm: TrueIf you want specific items to be protected

against editing and/or deletion, you can set a read only specifier:

mandatory: True

code: |

fruit.appendObject()

fruit[-1].important = True

fruit[-1].name.text = 'Apple'

fruit[-1].seeds = 10

fruit.appendObject()

fruit[-1].important = True

fruit[-1].name.text = 'Orange'

fruit[-1].seeds = 5

---

code: |

fruit[i].important = False

---

table: fruit.table

rows: fruit

columns:

- Name: |

row_item

- Seeds: |

row_item.seeds

edit:

- name.text

read only: importantIn this example, the attribute important of the table fruit

determines whether the item is “read only” or not. The first two

items in the DAList, which are added to the list in a code block,

have the important attribute set to True, while items that are

added by the user have the important attribute set to False.

Since read only is set to important, the Edit and Delete

buttons are not available for the items that have the important

attribute set to True.

If you want to allow editing but not deletion, or vice versa, the

value of the attribute can be set to a Python dictionary rather than

the value True or False. If the value of the key edit is false,

the “Edit” button will not be shown. If the value of the key