What is a function?

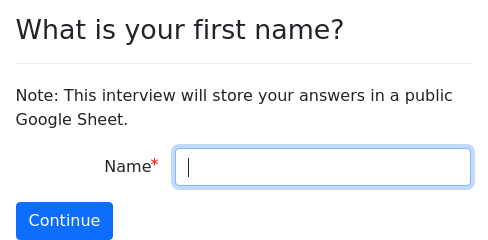

A function is a piece of code that takes one or more pieces of input and returns something as output or does something behind the scenes. For example:

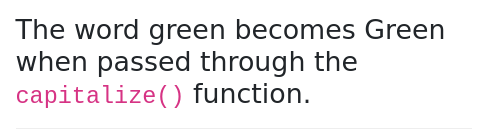

question: |

The word ${ color } becomes

${ capitalize(color) } when

passed through the

`capitalize()` function.

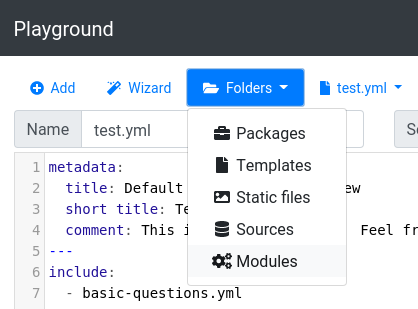

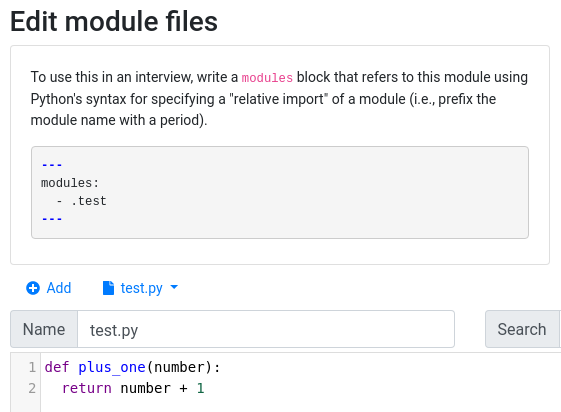

mandatory: TrueFunctions allow you to do a lot of different things in

docassemble. This section explains the standard docassemble

functions. If you know how to write Python code, you can write your

own functions and include them in your interview using a modules

block.

These functions are available automatically in docassemble

interviews (unless you set suppress loading util). To use them in

a Python module, put a line like this at the top of your .py file to

indicate which functions you want to import:

from docassemble.base.util import send_email, quote_paragraphsAll of the functions described in this section are available from the

docassemble.base.util module.

Functions for working with variable values

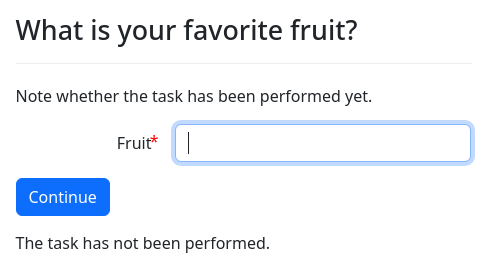

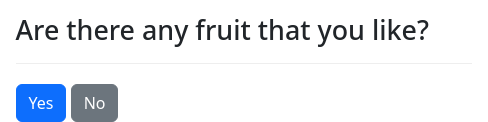

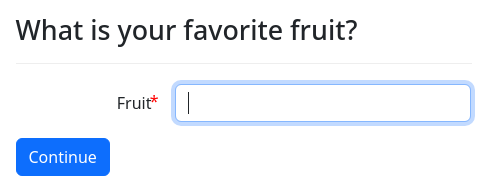

defined()

As explained in how docassemble runs your code, if your code or templates refer to a variable that is not yet defined, docassemble will stop what it is doing to ask a question or run code in an attempt to obtain a definition for that variable.

If you need to check to see if a variable has been defined yet without

triggering the process of defining it, you can use defined().

The defined() function takes as its argument the name of a variable.

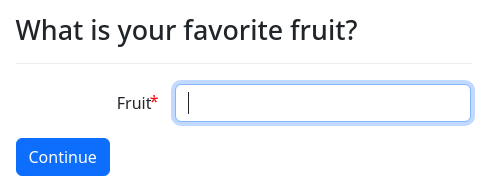

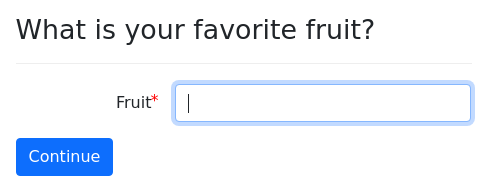

question: Summary

subquestion: |

Your favorite fruit is

${ favorite_fruit }.

% if defined('favorite_vegetable'):

Your favorite vegetable

is ${ favorite_vegetable }.

% else:

I do not know your favorite

vegetable.

% endif

mandatory: TrueIt is essential that you use quotation marks around the name of the variable. If you don’t, it is as if you are referring to the variable.

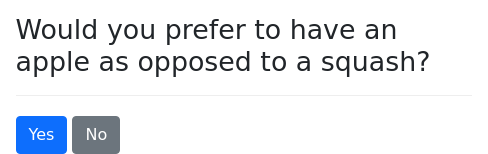

You should only use defined() in situations where it is absolutely

necessary. Your interview logic should be based on the values of

real variables, not the defined-ness of a variable. For example,

suppose you have an interview like this:

question: Are you married?

yesno: married

---

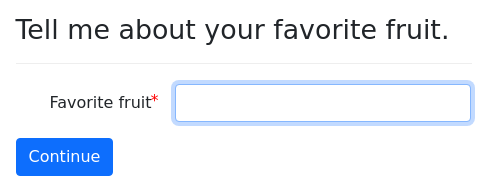

question: |

Key dates

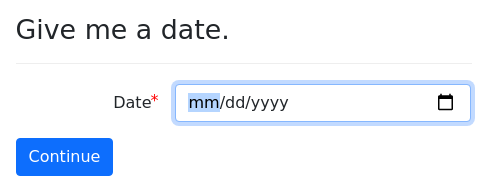

fields:

- "Birth date": date_of_birth

- "Marriage date": date_of_marriage

datatype: date

show if:

code: marriedYou might be tempted to write something like this in a DOCX template:

{% if defined(‘date_of_marriage’) %}Plaintiff is married and was married on {{ date_of_marriage }}.{% endif %}

This will work if your interview does not allow the user to go back

and edit answers. But if you allow the user to edit answers, what if

the user initially answered “Yes” to “Are you married?” and filled out

“Marriage date,” but then went back and changed the answer to the

“Are you married?” question to “No”? Now the value of

date_of_marriage is obsolete, but it is still exists. Because the

logic of your document is based on the defined-ness of a variable,

rather than the true fact of whether the user is married, it contains

an error.

The solution is to always base your logic off of actual facts:

{% if married %}Plaintiff is married and was married on {{ date_of_marriage }}.{% endif %}

By analogy, suppose that a lawyer worked on a case and wrote on a notepad: “we are still within the statute of limitations period; ok to bring tort claim.” Then, some time later, the lawyer is drafting a complaint, and wonders if he can raise a tort claim. Would he look at his notepad and see the words “ok to bring tort claim” and then conclude that he can bring a tort claim? No, he would analyze the facts as they currently stand and evaluate whether it was ok to bring a tort claim. The fact that something was once written on a notepad is not legally significant. What is legally significant is reality.

So, the defined() function is available, but using it is not

advisable unless it is impossible to substitute real facts for your

conditional statement.

The defined() function accepts an optional keyword argument

prior. If you set prior=True, then on screens that loaded because

the user pressed the Back button, defined() will look in the previous

set of interview answers (the set that was deleted by pressing the

Back button) to see if the variable was defined.

value()

The value() function returns the value of a variable, where the name

of the variable is given as a string.

question: Summary

subquestion: |

Your favorite fruit is

${ value('favorite_fruit') }.

mandatory: TrueThese two code blocks effectively do the exact same thing:

code: |

answer = value('meaning_of_life')

------

code: |

answer = meaning_of_lifeNote that value(meaning_of_life) and value("meaning_of_life") are

entirely different. The first will treat the value of the

meaning_of_life variable as a variable name. So if you set

meaning_of_life = 'chocolate', then value(meaning_of_life) will

attempt to find the value of the variable chocolate.

The value() function accepts an optional keyword argument

prior. If you set prior=True, then on screens that loaded because

the user pressed the Back button, value() will look in the previous

set of interview answers (the set that was deleted by pressing the

Back button) for the value of the variable.

The value() function is relatively inefficient. If you can use

regular Python expressions instead of value(), you should do so.

value() can be particularly helpful when called from a function

within a module. However, if you can rewrite your code so that the

variable’s value is passed to the function, or is available as an

object attribute, you should do so.

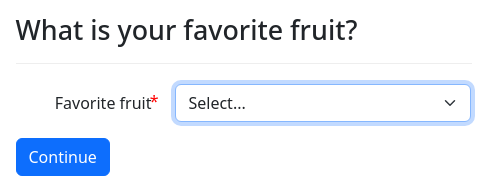

define()

The define() function defines a variable. The first argument is the

name of the variable (as a string) and the second argument is the

value you want the variable to have. Running

define('meaning_of_life', 42) has the same effect as running

meaning_of_life = 42.

code: |

define('favorite_fruit', 'apple')

---

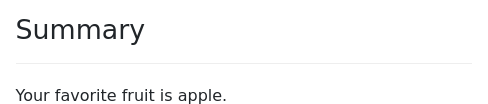

question: Summary

subquestion: |

Your favorite fruit is

${ favorite_fruit }.

mandatory: TrueNote that the second argument is the value itself. If you wanted to

do the equivalent of my_favorite_fruit = your_favorite_fruit, it

would be incorrect to do define('my_favorite_fruit',

'your_favorite_fruit'); you should instead do

define('my_favorite_fruit', your_favorite_fruit) or

define('my_favorite_fruit', value('your_favorite_fruit')).

undefine()

The undefine() function makes a variable undefined. The name

of the variable must be provided as a string. If the variable is not

defined to begin with, the function does not do anything.

undefine('favorite_fruit')This effectively does the same thing as the del statement in Python.

del favorite_fruitThe difference is that when using del, the variable must first

exist.

The undefine() function can be called with multiple variable names.

undefine('favorite_fruit', 'favorite_vegetable')Calling undefine in this way is faster than calling undefine()

multiple times.

invalidate()

The invalidate() function does what undefine() does, but it also

remembers the previous value and offers it as a default when a

question is asked again.

forget_result_of()

If you want a question with embedded blocks to be asked again,

or you want a mandatory block to run again, you need to run

forget_result_of() on the id of the block.

The forget_result_of() function takes one or more ids of blocks

as input and causes the results of those blocks to be forgotten. If

the id does not exist, or if the block has not yet been processed,

no error will be raised.

This example illustrates using forget_result_of() in conjunction

with del to ask a series of questions again, where some of the

questions contained embedded blocks.

id: favorite_food stage 2

question: |

Ok, are any of these your favorite food?

choices:

- Strawberries:

code: |

favorite_food = 'strawberries'

- Grapes:

code: |

favorite_food = 'grapes'

- Kiwi:

code: |

favorite_food = 'kiwi'

- Something else: continue

---

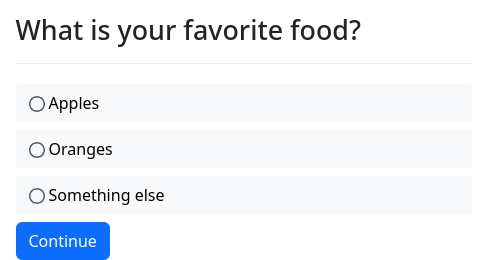

id: favorite_food stage 1

question: |

What is your favorite food?

choices:

- Apples:

code: |

favorite_food = 'apples'

- Oranges:

code: |

favorite_food = 'oranges'

- Something else: continue

---

event: reset_favorite_food

code: |

del favorite_food

forget_result_of("favorite_food stage 1", "favorite_food stage 2")The forget_result_of() function can also be used to reset a

mandatory block so that it will be run again.

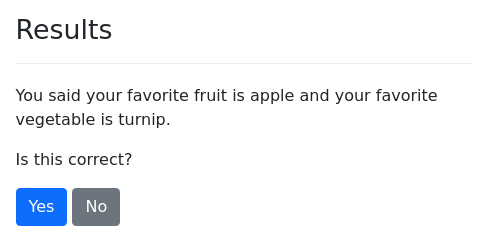

mandatory: True

code: |

favorite_fruit = "apple"

favorite_vegetable = "turnip"

id: initialize

---

mandatory: True

code: |

while not results_correct:

favorites_asked

favorites_reported

del results_correct

del favorites_asked

del favorites_reported

forget_result_of('initialize')

re_run_logic()

final_screen

---

question: |

Results

subquestion: |

You said your favorite fruit is

${ favorite_fruit } and

your favorite vegetable is

${ favorite_vegetable }.

Is this correct?

yesno: results_correct

---

question: |

What are your favorites?

fields:

- Favorite fruit: favorite_fruit

- Favorite vegetable: favorite_vegetable

continue button field: favorites_asked

---

question: |

Your favorites

subquestion: |

You said your favorite fruit is

${ favorite_fruit } and

your favorite vegetable is

${ favorite_vegetable }.

Press Continue to reset.

field: favorites_reported

---

event: final_screen

question: |

We are done.After resetting a mandatory block, you may want to call

re_run_logic(). Otherwise, the mandatory block will not have a

chance to run again until the next time the screen loads.

set_variables()

The set_variables() function is somewhat similar to define(),

except that instead of setting a particular variable name, it simply

updates the interview answers using a dictionary that you provide as

input, where the dictionary keys represent variable names and the

dictionary values represent values of those variables. For example,

if trustee is an Individual, and you do:

set_variables({'plaintiff': trustee, 'favorite_fruit': 'apple'})then this will have the same effect as doing:

plaintiff = trustee

favorite_fruit = 'apple'set_variables() accepts an optional keyword parameter

process_objects, which can be set to True or False. The default

is False. If process_objects is True, then the dictionary will

be transformed from docassemble’s “serializable” representation of

objects (see the .as_serializable() method) into actual Python

objects. For example, suppose you run the following code:

my_json = """\

{

"user": {

"_class": "docassemble.base.util.Individual",

"birthdate": "2000-04-01T00:00:00-05:00",

"favorite_fruit": "apple",

"instanceName": "user",

"name": {

"_class": "docassemble.base.util.IndividualName",

"instanceName": "user.name",

"uses_parts": true

}

}

}

"""

set_variables(json.loads(my_json), process_objects=True)This will have the effect of defining user as an Individual

object, where user.name is an IndividualName object and

user.birthdate is a DADateTime object.

When process_objects is True, any dictionary with a _class item

is converted into a Python object of the class represented by

_class, and the other items of the dictionary are converted into

attributes of that object. In addition, if any string looks like a

date or time (e.g. 2022-01-01, 23:15:00), an attempt will be made

to convert it into a DADateTime or datetime.time object.

Note that docassemble’s “JSON representation” of objects is not a

full-featured object serialization method. It cannot do everything

that Python’s pickle can do. At most, process_objects=True can be

used to import basic docassemble data structures.

re_run_logic()

The re_run_logic() function causes code to stop executing and causes

the interview logic to be evaluated from the beginning. You might

want to use this in cases when, after you make changes to variables,

you want the initial and not-yet-completed mandatory blocks to

be re-run in light of the changes you made.

If you use this, be careful that you do not create an infinite loop.

When the blocks are re-run, the result should not be encountering the

re_run_logic() function again, but should be something else, like

asking the user a question.

For an example of this in action, see the code example in the

forget_result_of() subsection.

reconsider()

The reconsider() function is similar to the reconsider modifier

on a code block. Each argument to reconsider() needs to be a

variable name, as text. E.g., reconsider('number_of_fruit',

'number_of_vegetables').

When reconsider() is run, it will undefine the given variables and

then seek their definitions. However, it will only do this once

in a given assembly process (i.e., once each time a screen loads).

Thus, even if your code block executes multiple times in a given

assembly process, each variable will only be recomputed one time.

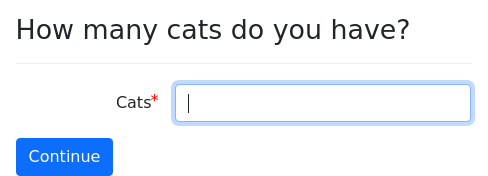

code: |

number_of_pets = number_of_cats + number_of_dogs

---

question: |

You have

${ nice_number(number_of_pets) }

pets.

subquestion: |

However, I do not think

you have been totally honest.

field: interim_report

---

question: |

Do you want a goldfish?

yesno: wants_goldfish

---

event: final_report

question: |

You really have

${ nice_number(number_of_pets) }

pets.

subquestion: |

% if wants_goldfish:

You would rather have a goldfish.

% endif

---

mandatory: True

code: |

interim_report

ask_dogs_again

reconsider('number_of_pets')

final_reportneed()

The need() function takes one or more variables as arguments and

causes docassemble to ask questions to define each of the

variables if the variables are not already defined. Note that with

need(), you do not put quotation marks around the variable name.

For example, this mandatory code block expresses interview logic

requiring that the user first be shown a splash screen and then be

asked questions necessary to get to the end of the interview.

mandatory: True

code: |

need(user_shown_splash_screen, user_shown_final_screen)This happens to be 100% equivalent to writing:

mandatory: True

code: |

user_shown_splash_screen

user_shown_final_screenSo the need() function does not “do” anything. However, writing

need() functions in your code probably makes your code more readable

because it helps you convey in “natural language” that your interview

“needs” these variables to be defined.

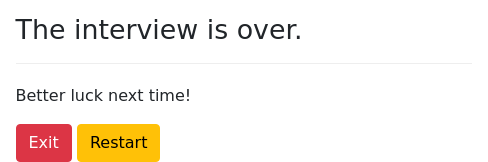

force_ask()

Usually, docassemble only asks a question when it encounters a

variable that is not defined. However, with the force_ask function,

you can cause such a condition to happen manually, even when a

variable is already defined.

In this example, we use force_ask to cause docassemble to ask a

question that has already been asked.

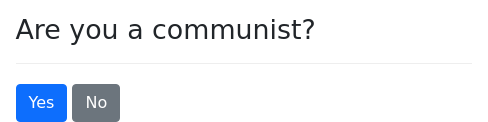

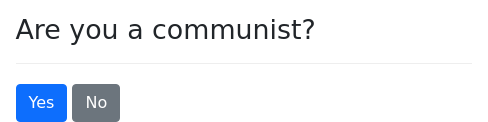

question: |

Are you a communist?

yesno: user_is_communist

---

mandatory: True

code: |

if user_is_communist and user_reconsidering_communism:

user_reconsidering_communism = False

force_ask('user_is_communist')

---

question: |

I suggest you reconsider your

answer.

field: user_reconsidering_communism

---

question: |

% if user_is_communist:

I am referring your case to

Mr. McCarthy.

% else:

I am glad you are a true

American.

% endif

mandatory: TrueThis may be useful in particular circumstances. However,

force_ask() cannot be used with all types of questions. For

example, it cannot be relied upon to re-ask questions that:

- Use the

generic objectmodifier (and the special variablex) or iterators (i,j, etc.); - Contain embedded blocks.

The use of force_ask() is discouraged, unless you are an expert and

you know what you are doing. Usually, there is a more elegant way to

craft your interview logic than by using force_ask(). If the

question you want to ask is a single-variable question (field with

choices, field with buttons, yesno, noyes), you can use

reconsider(). If the question has fields, you can set a

continue button field. You might also find it useful to use the

undefine() and re_run_logic() functions.

Note that variable names given to force_ask must be in quotes. If

your variable is favorite_fruit, you need to write

force_ask('favorite_fruit'). If you write

force_ask(favorite_fruit), docassemble will assume that, for

example, apples is a variable in your interview.

force_ask() works by triggering the actions mechanism. This means

that in a multi-user interview, force_ask() only changes the current

question for the current user; each user has their own active

action, or list of active actions.

Note also that no code that comes after force_ask() will ever be

executed. Once the force_ask() function is called, the code stops

running, and the question indicated by the variable name will be

shown. That is why, in the example above, we set

user_reconsidering_communism to False before calling

force_ask(). The variable user_reconsidering_communism, which had

been set to True by the “I suggest you reconsider your answer”

question, is set to False before the call to force_ask so that the

mandatory code block does not get stuck in an infinite loop.

A different way to reask a question is to use the built-in Python

operator del. This makes the variable undefined. Instead of

writing:

mandatory: True

code: |

if user_is_communist and user_reconsidering_communism:

user_reconsidering_communism = False

force_ask('user_is_communist')we could have written:

mandatory: True

code: |

if user_is_communist and user_reconsidering_communism:

user_reconsidering_communism = False

del user_is_communistThis will also cause the user_is_communist question to be asked

again. This is more robust than using force_ask because the user

cannot get past the question simply by refeshing the screen.

The force_ask() function can also be given the names of variables

that refer to event blocks. The screen will be shown, but no

variable will be defined.

You can use force_ask() to ask a series of questions. Just list

each variable one after another.

mandatory: True

code: |

favorite_fruit

favorite_vegetable

favorite_fungus

told_to_review

if not all_reviewed:

all_reviewed = True

force_ask('favorite_fruit', 'favorite_vegetable', 'favorite_fungus')

final_screen

---

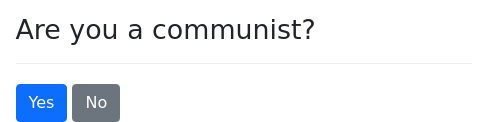

question: |

What is your favorite fruit?

fields:

- Favorite fruit: favorite_fruit

---

question: |

What is your favorite vegetable?

fields:

- Favorite vegetable: favorite_vegetable

---

question: |

What is your favorite fungus?

fields:

- Favorite: favorite_fungus

---

question: |

Please verify your answers.

subquestion: |

I will ask each question again.

Make any changes that you think

are necessary.

field: told_to_review

---

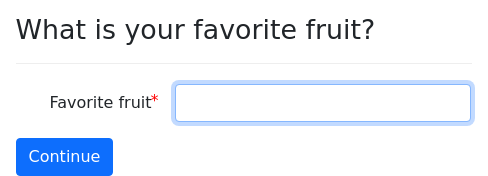

event: final_screen

question: |

Thank you.

subquestion: |

You like

${ favorite_fruit },

${ favorite_vegetable },

and

${ favorite_fungus }.

---

code: |

all_reviewed = FalseThe second and subsequent arguments to force_ask() can specify

actions with arguments. If an argument to force_ask() is a

Python dictionary with keys action and arguments, the specified

action will be run. (Internally, docassemble uses the actions

mechanism to force the interview to ask these questions.)

If you give force_ask() the name of a variable that no question

can define, then force_ask() will quietly ignore it. Thus you can

use conditional logic within a force_ask() sequence by adding if

modifiers to each question that specify under what conditions the

question should be asked.

In addition to giving force_ask() variables and actions, you can

give it a dictionary containing a special command.

force_ask('favorite_fruit', {'recompute': 'dessert_cost'}, 'favorite_vegetable')force_ask('favorite_fruit', {'recompute': ['dessert_cost', 'breakfast_cost']}, 'favorite_vegetable')force_ask('favorite_fruit', {'recompute': ['dessert_cost', 'breakfast_cost']}, 'favorite_vegetable')force_ask('favorite_fruit', {'set': {'fruit_known': True}}, 'favorite_vegetable')force_ask('favorite_fruit', 'favorite_vegetable', {'set': [{'fruit_known': True}, {'vegetable_known': True}]})

For more information on how these data structures work, see the

subsection on customizing the display of review options.

force_ask() accepts the optional keyword parameter

forget_prior. If forget_prior is set to a true value, then any

pending actions will be forgotten. If forget_prior is not provided,

then force_ask() will simply add one or more actions to the “stack”

of pending actions.

Here is an example that demonstrates the effect of forget_prior.

mandatory: True

question: First page

subquestion: |

[Go to second page](${ url_action('second_page') })

---

question: Second page

subquestion: |

[Go to third page](${ url_action('third_page') })

continue button field: second_page

---

question: Third page

subquestion: |

[Ask about food](${ url_action('food_preferences') })

[Ask about food with forget prior](${ url_action('food_preferences_forget_prior') })

continue button field: third_page

---

#event: food_preferences

code: |

favorite_fruit

favorite_vegetable

food_preferences = True

#force_ask('favorite_fruit', 'favorite_vegetable')

---

event: food_preferences_forget_prior

code: |

force_ask('favorite_fruit', 'favorite_vegetable', forget_prior=True)

---

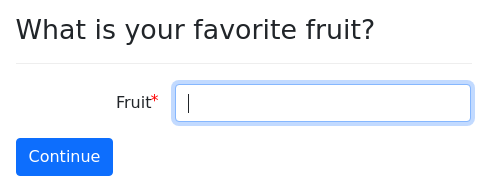

question: |

What is your favorite fruit?

fields:

- Favorite fruit: favorite_fruit

---

question: |

What is your favorite vegetable?

fields:

- Favorite vegetable: favorite_vegetableforce_ask() accepts the optional keyword parameter evaluate. If

evaluate is set to True, then the variable names given to

force_ask() will be evaluated to determine their intrinsic

names. For example, if you have:

objects:

- plaintiffs: DAList.using(object_type=Individual)

- defendants: DAList.using(object_type=Individual)

---

code: |

if been_sued:

user = defendants[0]

else:

user = plaintiffs[0]

---

mandatory: True

code: |

user.name.firstThen if you do force_ask('user.name.first'), then docassemble

will look for a question that literally defines

user.name.first. However, if you actually want docassemble to

look for a question that defines plaintiffs[0].name.first or

defendants[0].name.first, then you can call

force_ask('user.name.first', evaluate=True). Then docassemble

will inspect user, then user.name, and it will find that the

.instanceName of user.name is, e.g., plaintiffs[0].name, and it

will look for a question that defines plaintiffs[0].name.first.

Instead of using evaluate, you could instead write

force_ask(user.name.attr_name('first')). This ensures that

force_ask() is called on the correct name for the attribute.

A function that is related to force_ask() is force_gather().

force_gather() cannot force the-reasking of a question to define a

variable that has already been defined, but it does not have the

limitations on question types that force_ask() has.

force_gather()

The force_gather() function is very similar to force_ask(),

except it affects the interview logic for all users of the interview,

not just the current user.

initial: True

code: |

process_action()

---

event: gather_it

code: |

force_gather('favorite_food')Calling force_gather('favorite_food') means “until favorite_food

is defined, keep asking questions that offer to define

favorite_food, and satisfy any prerequisites that these questions

require.”

Normally, you will not need to use either force_ask() or

force_gather(); you can just mention the name of a variable in

your questions or code blocks, as part of your interview

logic, and docassemble will make sure that the variables get

defined. The force_ask() and force_gather() functions are

primarily useful when you are using actions to do things that are

outside the normal course of the interview logic.

dispatch()

The dispatch() function provides logic so that an interview can

present a menu system within a screen. For example:

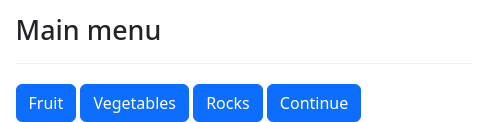

mandatory: True

code: |

dispatch('main_menu_selection')

final_screen

---

question: |

Main menu

field: main_menu_selection

buttons:

- Fruit: fruit_menu

- Vegetables: vegetable_menu

- Rocks: rocks_page

- Continue: Null

---

code: |

fruit_menu = dispatch('fruit_menu_selection')

---

question: |

Fruit menu

field: fruit_menu_selection

choices:

- Apple: apple

- Peach: peach

- Back: Null

---

code: |

vegetable_menu = dispatch('vegetable_menu_selection')

---

question: |

Vegetable menu

field: vegetable_menu_selection

choices:

- Turnip: turnip

- Potato: potato

- Back: Null

---

question: Rocks screen

field: rocks_page

---

question: Apples screen

subquestion: |

% if likes_apples:

You like apples.

% endif

field: apple

---

question: |

Do you like apples?

yesno: likes_apples

---

question: Peaches screen

subquestion: |

You selected

${ main_menu_selection }

on the main menu and

${ fruit_menu_selection }

on the fruit menu.

field: peach

---

event: turnip

question: Turnip screen

subquestion: |

You cannot go forward from

the turnip screen.

---

question: Potato screen

field: potato

---

event: final_screen

question: |

Done with the interview.To make a menu, you need to add a few components to your interview:

- Some code that runs

dispatch()in order to launch the menu at a particular place in your interview logic. - A screen that shows the menu. This is typically a multiple-choice question in which each choice represents a screen that the user can visit.

- Screens corresponding to each choice. These can be standalone screens, or they can be sub-menus.

In the example above, the main menu is a multiple-choice question

that sets the variable main_menu_selection.

When the interview logic calls dispatch('main_menu_selection'), it

looks for a definition of the variable main_menu_selection. It

finds a multiple-choice question that offers to define

main_menu_selection. This question will set the variable

to one of four values:

fruit_menuvegetable_menurocks_pageNull

The first three values are the names of other variables in the

interview. Note that in the interview, fruit_menu and

vegetable_menu are variables defined by code blocks, and

rocks_page is defined by a question block. If the user selects

one of these choices, the interview will look for a definition of the

selected variable. This all done by the dispatch() function.

The last value, Null, is special; it ends the menu. (Note that

Null or null is a special value in YAML; it becomes None in

Python.) When the user selects “Continue,” the dispatch()

function will end. In this sample interview, the next step after the

menu is to show the final_screen. Thus, when the user selects

“Continue,” the user sees the final_screen question. If you want

the interview logic to be able to move past the dispatch() function,

you must include a Null option.

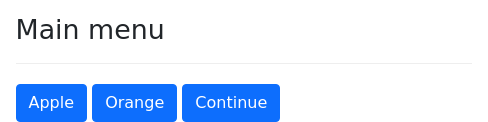

This sample interview features two sub-menus. You can tell this

because the variable fruit_menu is defined with:

fruit_menu = dispatch('fruit_menu_selection')and the variable vegetable_menu is defined with:

vegetable_menu = dispatch('vegetable_menu_selection')If the user selects “Fruit” from the main menu, the interview will

seek a definition of fruit_menu. This in turn leads to calling the

dispatch() function on 'fruit_menu_selection'. This leads to

seeking a definition of the variable fruit_menu_selection. If the

user selects the Null option on this menu, the user will go back to

the main menu.

If the user selects “Rocks” from the main menu, the interview will

seek a definition of rocks_page. In this case, the block that

offers to define rocks_page is a question with a “Continue”

button. When the user presses “Continue” on the “Rocks screen,” the

user will return to the menu.

Note that when the interview seeks definitions of variables and

displays screens, it will ask questions to satisfy prerequisites. For

example, when the user selects “Apple” from the “Fruit menu,” the

interview will seek the definition of apple, but in order to pose

the question that defines apple, it needs the definition of

likes_apples. So it will stop and ask “Do you like apples?” before

proceeding to the question that defines apple.

One very important thing to know about the dispatch() function is

that the variables it uses to navigate among the screens are

temporary. After the call to dispatch('main_menu_selection'), the

variables main_menu_selection, fruit_menu, fruit_menu_selection,

apple, rocks_page, etc., will all be undefined. However,

questions will be able to access these variables from within the

dispatch() function. For example, the “Peaches screen” successfully

accesses the values of main_menu_selection and

fruit_menu_selection.

If you want to gather information about what screens your user visited

or did not visit, you can use prerequisites to do so. Here is an

example that uses the need specifier to run a code block when a

user selects a menu item.

mandatory: True

code: |

visited_apple = False

visited_orange = False

---

mandatory: True

code: |

dispatch('main_menu_selection')

final_screen

---

question: |

Main menu

field: main_menu_selection

buttons:

- Apple: apple

- Orange: orange

- Continue: Null

---

question: Apple screen

field: apple

need: apple_tracked

---

code: |

visited_apple = True

apple_tracked = True

---

question: Orange screen

field: orange

need: orange_tracked

---

code: |

visited_orange = True

orange_tracked = True

---

event: final_screen

question: |

All done.

subquestion: |

% if visited_apple:

You visited the apple menu.

% endif

% if visited_orange:

You visited the orange menu.

% endifall_variables()

The all_variables() function returns all of the variables defined in

the interview session as a simplified Python dictionary.

mandatory: True

question: |

Interview dictionary

subquestion: |

The variables in the dictionary are:

`${ all_variables() }`The resulting Python dictionary is suitable for conversion to JSON

or other formats. Each object is converted to a Python

dictionary. Each datetime or DADateTime object is converted

to its isoformat(). Other objects are converted to None.

If you want the raw Python dictionary representing the variables

defined in the interview session, you can call

all_variables(simplify=False). The result is not suitable for

conversion to JSON. This raw Python dictionary will be linked to

the current interview answers, so that if you use the Python is

operator to test for equivalence between objects, you will see that

they are equivalent. Therefore, if you try to edit the output of

all_variables(simplify=False), you may be affecting the interview

variables in unwanted ways. If you want the result of

all_variables(simplify=False) to be a distinct copy of the interview

answers, call it using all_variables(simplify=False,

make_copy=True).

docassemble keeps a dictionary called _internal in the interview

variables and uses it for a variety of internal purposes. There is

also an object called nav that is used for tracking which sections

of an interview the user has visited. By default, _internal and

nav are not included in the output of all_variables(). If you

want _internal and nav to be included, set the optional keyword

parameter include_internal to True.

The all_variables() function also has three special behaviors:

all_variables(special='titles')will return a Python dictionary containing information set by themetadatainitial block and theset_parts()function.all_variables(special='metadata')will return a dictionary representing the “metadata” indicated in themetadatainitial blocks of the interview. (If multiple blocks exist, information is “layered” so that keys in later blocks overwrite keys in earlier blocks.) Unlike the'titles'option, the information returned here is not updated to take into account changes made programmatically by theset_parts()function.all_variables(special='tags')will return a Python set containing the current set of tags defined for the interview session.

Functions for special responses

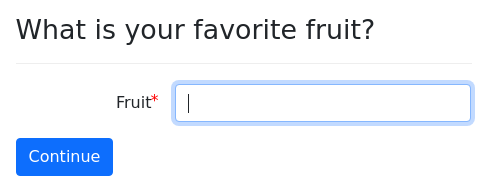

message()

code: |

message("The interview is over.", "Better luck next time!")

mandatory: TrueThe message() function causes docassemble to stop what it is

doing and present a screen to the user that contains a given message.

By default, the user will be offered an “exit” button and a “restart” button, but these choices can be configured.

The first argument is the title of the screen the user will see (the

question). The second argument, which is optional, indicates the

text that will follow the title (the subquestion).

The message() function also takes keyword arguments. The following

do the same thing:

message("This is the big part of the question", "This is the smaller part of the question")message(question="This is the big part of the question", subquestion="This is the smaller part of the question")

The optional keyword arguments influence the appearance of the screen:

message("Bye!", "See ya later", show_restart=False)will show the Exit button but not the Restart button.message("Bye!", "See ya later", show_exit=False)will show the Restart button but not the Exit button.message("Bye!", "See ya later", url="https://www.google.com"): clicking the Exit button will take the user to Google.message("Bye!", "See ya later", show_leave=True)will show a Leave button instead of the Exit button.message("Bye!", "See ya later", show_leave=True, show_exit=True, show_restart=False)will show a Leave button and an Exit button.message("Bye!", "See ya later", buttons=[{"Learn More": "exit", "url": "https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spinning_wheel"}])will show a “Learn More” button that exits to Wikipedia.

response()

The response() command allows the interview developer to use code to

send a special HTTP response. Instead of seeing a new docassemble

screen, the user will see raw content as an HTTP response, or be

redirected to another web site. As soon as docassemble runs the

response() command, it stops what it is doing and returns the

response.

There are four different types of responses, which you can invoke by

using one of four keyword arguments: response, binaryresponse,

file, and url. There is also an optional keyword argument

content_type, which determines the setting of the Content-Type

header. (This is not used for url responses, though.) The

response() function accepts the optional keyword parameter

response_code. The default HTTP response code is 200 but you can

use response_code to set it to a different value.

The four response types are:

response: This is treated as text and encoded to UTF-8. For example, if you have some data in a dictionaryinfoand you want to return it in JSON format, you could doresponse(response=json.dumps(info), content_type='application/json'). If thecontent_typekeyword argument is omitted, the Content-Type header defaults totext/plain; charset=utf-8.binaryresponse: This is likeresponse, except that the data provided as thebinaryresponseis treated as binary bytes rather than text, and it is passed directly without any modification. You could use this to transmit images that are created using a software library like the Python Imaging Library. If thecontent_typekeyword argument is omitted, the Content-Type header defaults totext/plain; charset=utf-8.file: The contents of the specified file will be delivered in response to the HTTP request. You can supply one of two types of file designators: aDAFileobject (e.g., an assembled document or an uploaded file), or a reference to a file in a docassemble package (e.g.,'moon_stars.jpg'for a file in the static files folder of the current package, or'docassemble.demo:data/static/orange_picture.jpg'to refer to a file in another package).url: If you provide a URL, the web server will redirect the user’s browser to the provided URL.

Here is an example that demonstrates response:

mandatory: True

code: |

data = {'fruit': 'apple', 'pieces': 2}

response(json.dumps(data), content_type="application/json")Here is an example that demonstrates the binaryresponse:

sets: all_done

code: |

svg_image = """\

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8" standalone="no"?>

<svg

xmlns:dc="http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/"

xmlns:cc="http://creativecommons.org/ns#"

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:svg="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"

xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg"

version="1.1"

id="svg2"

width="100"

height="100">

<circle

id="circle4"

fill="red"

stroke-width="3"

stroke="black"

r="40"

cy="50"

cx="50" />

</svg>

"""

response(binaryresponse=svg_image, content_type="image/svg+xml")The following example shows how you can make information entered into an interview available to a third-party application through a URL that returns data in JSON format.

objects:

- user: Individual

---

mandatory: True

code: |

multi_user = True

---

event: query_fruit

code: |

data = {'fruit': favorite_fruit, 'pieces': number_of_pieces}

json_response(data)

---

mandatory: True

question: |

You currently have

${ nice_number(number_of_pieces) }

${ noun_plural('piece', number_of_pieces) }

of

${ noun_singular(favorite_fruit) }.

subquestion: |

Use

[this link](${ interview_url_action('query_fruit') })

to query the information from

another application.

You can also change the

[fruit](${ url_action('favorite_fruit') })

and the

[number of pieces](${ url_action('number_of_pieces') }).Note the following about this interview.

- We set

multi_usertoTruein order to disable server-side encrpytion. This allows an external application to access the interview without logging in as the user. - The

query_fruiteventcode will be run as an action when someone accesses the link created byinterview_url_action().

The response() command can be used to integrate a docassemble

interview with another application. For example, the other

application could call docassemble with a URL that includes an

interview file name (argument i) along with a number of

URL arguments. The interview would process the information passed

through the URLs, but would not ask any questions. It would instead

return an assembled document using response().

attachment:

name: A file

file: test_file

variable name: the_file

valid formats:

- pdf

content: |

Hello, ${ url_args.get('name', 'you') }!

---

mandatory: True

code: |

response(file=the_file.pdf)Here is a link that runs this interview. Notice how the name “Fred” is embedded in the URL. The result is an immediate PDF document.

When you write code that runs in a scheduled task, you can use

response() to finish the scheduled task. In this context, you can

pass the optional keyword argument sleep with a number of seconds

that you want to pause after the task is finished. This can be useful

when your scheduled tasks would overwhelm your SQL server if

executed one after another without pauses.

json_response()

Calling json_response(data) is (basically) a shorthand for

response(binaryresponse=json.dumps(data).encode('utf-8'), content_type="application/json").

It takes a single positional argument and returns it as an HTTP response in JSON format.

Here is an example of how json_response() can be used in combination

with the action_call() JavaScript function.

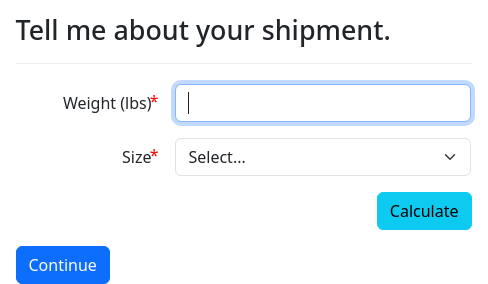

mandatory: True

question: |

Tell me about your shipment.

fields:

- Weight (lbs): weight

datatype: number

- Size: size

choices:

- Small box: 1

- Medium box: 2

- Large box: 3

- html: |

<button id="calcButton" class="btn btn-info float-end" type="button">Calculate</button>

<span id="calcResults"></span>

script: |

<script>

$("#calcButton").on('click', function(){

var theWeight = parseFloat(val('weight'))

var theSize = parseInt(val('size'))

if (theWeight && theSize){

action_call('calc', {weight: theWeight, size: theSize}, function(data){

$("#calcResults").html("That will cost $" + data.cost.toLocaleString('en-US') + ".");

});

}

})

</script>

---

event: calc

code: |

json_response({'cost': 4.44 + action_argument('weight') * 5.2 + action_argument('size') * 13.1})The json_response() function accepts the optional keyword parameter

response_code. The default response code is 200 but you can use

response_code to set it to a different value.

Another way to get JSON output from docassemble is to use the JSON interface, which provides a JSON representation of a docassemble screen. This can be useful if you are developing your own front end to docassemble.

variables_as_json()

The variables_as_json() function acts like response() in the

example above, except that is returns all of the variables in the

interview session dictionary in JSON format.

mandatory: True

code: |

multi_user = True

---

event: query_variables

code: |

variables_as_json()

---

mandatory: True

question: |

You currently have

${ nice_number(number_of_pieces) }

${ noun_plural('piece', number_of_pieces) }

of

${ noun_singular(favorite_fruit) }.

subquestion: |

Use

[this link](${ interview_url_action('query_variables') })

to query the information from

another application.

You can also change the

[fruit](${ url_action('favorite_fruit') })

and the

[number of pieces](${ url_action('number_of_pieces') }).The variables_as_json() function simplifies the interview variables

in the same way that the all_variables() function does. Like

all_variables(), it takes an optional keyword argument

include_internal, which is False by default, but when True,

includes the internal variables _internal and nav in the output.

command()

mandatory: True

code: |

command('exit', url=target_url)

---

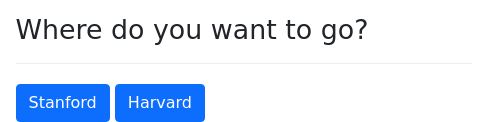

question: |

Where do you want to go?

field: target_url

buttons:

- Stanford: "http://stanford.edu/"

- Harvard: "http://www.harvard.edu/"The command() function allows the interview developer to trigger an

exit from the interview using code, rather than having the user click

an exit, restart, leave or signin button.

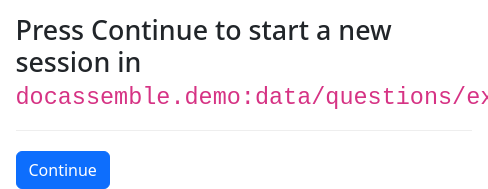

The first argument to command() is one of the following:

'restart': deletes the user’s answers and puts them back at the start of the interview.'new_session': starts a new session for the same interview without deleting the user’s answers.'exit': deletes the user’s answers and redirects them to a web site'logout': logs the user out and redirects them to a web site.'exit_logout': deletes the user’s answers, logs the user out (if logged in) and redirects them to a web site.'leave': redirects the user to a web site without deleting the user’s answers.'signin': redirects the user to the sign-in screen.

The optional keyword argument url provides a URL to which the user

should be redirected. The value of exitpage will be used if no

url is provided.

Note that the special buttons perform a similar function to

command(). See also the starting an interview from the beginning

subsection for URL parameters that reset interview sessions.

The command() function can also be used to instruct the user’s web

browser to wait for a period of time and then reload the screen.

command('wait')As with the other command() options, calling command('wait')

causes code execution to stop on the server. (It raises an exception,

which is trapped.) The server returns a response to the web browser,

instructing the web browser to wait for four seconds and then query

the server again. The user will continue seeing the previous screen,

and a spinner will appear. If the user reloads the screen, or if the

interview logic calls command('wait') when the user first visits the

interview, the user will see a screen that says “Please wait . . .”

If you want the browser to query the server after a

different number of seconds, set the seconds parameter.

command('wait', sleep=10)If you want a message other than “Please wait . . .” you can set

question_text and subquestion_text:

command('wait', question_text='Processing . . .', subquestion_text='The computer is busy. Be patient.')Text transformation functions

from_b64_json()

Takes a string as input, converts the string from base-64, then parses the string as JSON, and returns the object represented by the JSON.

This is an advanced function that is used by software developers to integrate other systems with docassemble.

plain(), bold(), and italic()

The functions plain(), bold(), and italic() are useful when

including variables in a template.

For example, if you write:

subquestion: |

* Your phone number: **${ phone_number }**

* Your fax number: **${ fax_number }**Then the values of the two variables will have bold face markup, but if one of them is empty, you will get asterisks instead of what you presumably wanted, which was no text at all.

- Your phone number: 202-555-2030

- Your fax number: ****

Instead, you can write:

subquestion: |

* Your phone number: ${ bold(phone_number) }

* Your fax number: ${ bold(fax_number) }This leads to:

- Your phone number: 202-555-2030

- Your fax number:

Alternatively, you can pass an optional keyword argument, default,

if it should plug in something different when empty.

subquestion: |

* Your phone number: ${ bold(phone_number, default='Not available') }

* Your fax number: ${ bold(fax_number, default='Not available') }This leads to:

- Your phone number: 202-555-2030

- Your fax number: Not available

Calling italic('apple') function returns _apple_.

The plain() function does not supply any formatting, but it

will substitute the default keyword argument.

space_to_underscore()

If user_name is John Wilkes Booth,

space_to_underscore(user_name) will return John_Wilkes_Booth.

This is useful if you do not want spaces in the filenames of your

attachments. This function will also do basic filename sanitization

to remove dangerous characters and command injection.

sets: user_done

question: Thanks!

subquestion: Here is your letter.

attachment:

- name: A letter for ${ user_name }

filename: Letter_for_${ space_to_underscore(user_name) }

content file: letter.mdsingle_to_double_newlines()

Under the rules of Markdown, you need to insert two newlines to

break a paragraph. Sometimes you have text where one newline

represents a paragraph, but you want the single newlines to count as

paragraph breaks. The function single_to_double_newlines() will

convert the text for you.

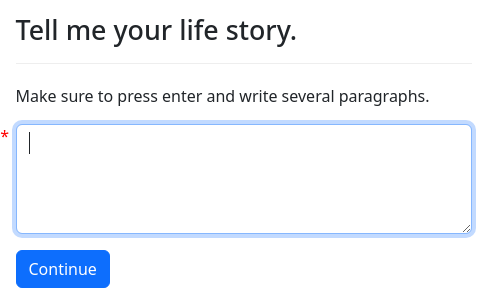

mandatory: True

question: |

Here is your first book.

attachment:

name: Story of My Life

filename: life_story

content: |

[BOLDCENTER] My Life Story

${ single_to_double_newlines(life_story) }

[CENTER] The End.single_paragraph()

single_paragraph(user_supplied_text) will replace any linebreaks in

user_supplied_text with spaces. This allows you to do things like:

question: Summary of your answers

subquestion: |

When I asked you the meaning of life, you said:

> ${ single_paragraph(meaning_of_life) }

field: ok_to_proceedIf you did not remove line breaks from the text, then if the

meaning_of_life contained two consecutive line breaks, only the

first paragraph of the answer would be indented.

verbatim()

If you are inserting user-supplied input into a document or onto the

screen, it is possible that the text may contain characters that will

result in undesired formatting changes. For example, the input may

contain Markdown codes, HTML codes, or LaTeX codes. To avoid the

effects of such characters, wrap the text with the verbatim()

function.

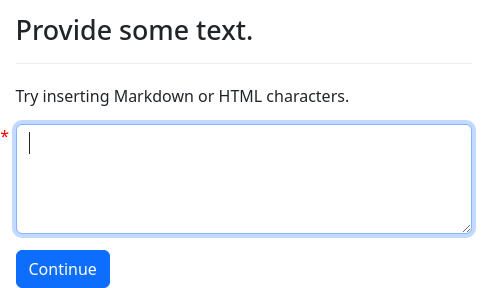

question: |

Provide some text.

subquestion: |

Try inserting Markdown or HTML characters.

fields:

no label: user_input

input type: area

---

mandatory: True

question: |

This content should be devoid

of formatting.

subquestion: |

${ verbatim(user_input) }

attachment:

content: |

${ verbatim(user_input) }quote_paragraphs()

The quote_paragraphs() function adds Markdown to text so that it

appears as a quotation.

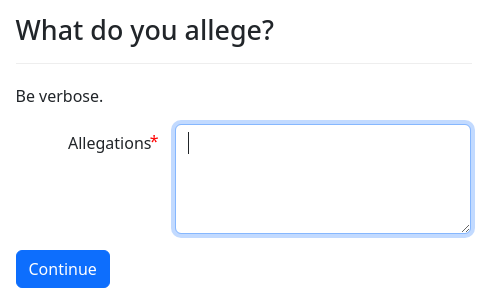

mandatory: True

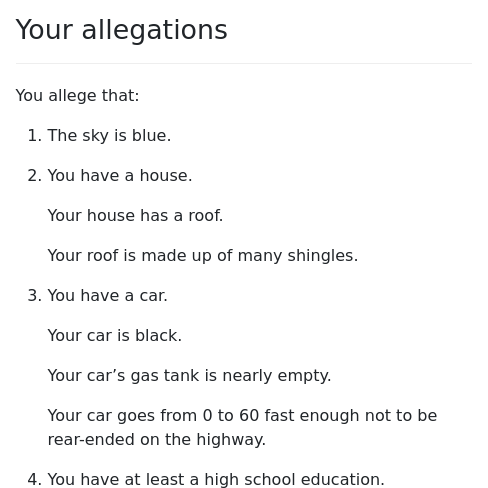

question: |

Your allegations

subquestion: |

You allege that:

${ quote_paragraphs(allegations) }indent()

The indent() function adds four spaces to the beginning of each line

of the given Markdown to text. This needs to be used if you are

inserting a table or a paragraph of user text into the context of a

Markdown bullet-point or itemized list, and you want the text to be

part of an item. If you do not indent the text, the text will be

treated as a new paragraph that ends the list.

mandatory: True

question: |

Your allegations

subquestion: |

You allege that:

1. The sky is blue.

2. You have a house.

Your house has a roof.

Your roof is made up of many

shingles.

3. You have a car.

${ indent(car_allegations) }

4. You have at least a high

school education.

---

template: car_allegations

content: |

Your car is black.

Your car's gas tank is nearly empty.

Your car goes from 0 to 60 fast enough

not to be rear-ended on the highway.fix_punctuation()

The fix_punctuation() function ensures that the given text ends with

a punctuation mark. It will add a . to the end of the text if no

punctuation is present at the end. To use a different punctuation

mark, set the optional keyword argument mark to the text you want to

use.

A call to fix_punctuation(reason) will return:

I have a valid claim.ifreasonisI have a valid claimI have a valid claim.ifreasonisI have a valid claim.I have a valid claim!ifreasonisI have a valid claim!I have a valid claim?ifreasonisI have a valid claim?

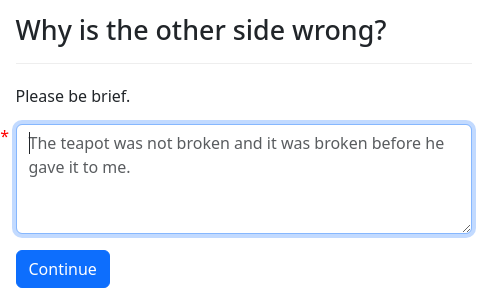

mandatory: true

question: |

What to do in court.

subquestion: |

Tell the court,

"Please grant my petition.

${ fix_punctuation(rationale) }"

---

question: |

Why is the other side wrong?

subquestion: |

Please be brief.

fields:

- no label: rationale

input type: area

hint: |

The teapot was not broken

and it was broken before he

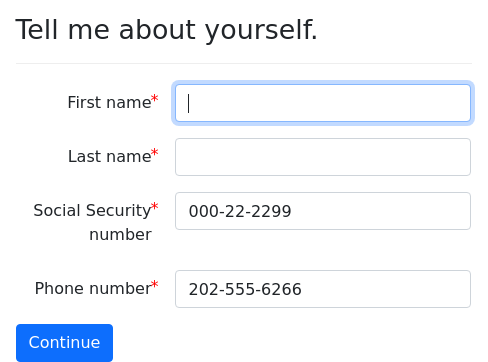

gave it to me.redact()

The redact() function is used when preparing redacted and unredacted

versions of a document. For example, instead of referring to

client.ssn in a document, you can refer to redact(client.ssn).

Then, in the final document, a redaction mark will be included instead

of the client’s Social Security number. However, if the document is

assembled with redact: False, the Social Security number will be

included.

Here is an example of redact() being used when generating a PDF and

RTF file from Markdown:

template: petition_text

content: |

Dear Judge,

My name is ${ user }.

I have a claim against

the defendant. A big one.

My SSN is ${ redact(user.ssn) }.

My phone number is

${ user.phone_number }.

My home address is:

${ redact(user.address) }

I demand ${ currency(money_claimed) }.

Thank you.

Sincerely,

${ user }

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Here is your document.

subquestion: |

You need to print both copies

and file them in court.

The unredacted version goes

to the judge, and the redacted

version will go in the public

record.

attachments:

- name: Unredacted petition

filename: petition_unredacted

redact: False

valid formats:

- pdf

- rtf

- docx

content: |

${ petition_text }

- name: Redacted petition

filename: petition_redacted

valid formats:

- pdf

- rtf

- docx

content: |

${ petition_text }Here is the same example, but with a docx template file named

redact_demo.docx:

mandatory: True

question: |

Here is your document.

subquestion: |

You need to print both copies

and file them in court.

The unredacted version goes

to the judge, and the redacted

version will go in the public

record.

attachments:

- name: Unredacted petition

redact: False

filename: petition_unredacted

docx template file: redact_demo.docx

- name: Redacted petition

filename: petition_redacted

docx template file: redact_demo.docxHere is the same example, but with a pdf template file named

redact_demo.pdf:

mandatory: True

question: |

Here is your document.

subquestion: |

You need to print both copies

and file them in court.

The unredacted version goes

to the judge, and the redacted

version will go in the public

record.

attachments:

- name: Unredacted petition

redact: False

filename: petition_unredacted

pdf template file: redact_demo.pdf

field code:

- today_date: today()

- name: user

- ssn: redact(user.ssn)

- phone: user.phone_number

- address: redact(user.address)

- money: currency(money_claimed)

- name: Redacted petition

filename: petition_redacted

pdf template file: redact_demo.pdf

field code:

- today_date: today()

- name: user

- ssn: redact(user.ssn)

- phone: user.phone_number

- address: redact(user.address)

- money: currency(money_claimed)The redact() function is intended to be called the markup of

documents, as demonstrated in the various examples above. It is only

in this context that the redact() function knows whether you have

set redact: False or not. The redact() function can be from other

contexts, but the result may not be what you want; for example, you

may see redactions even though you set redact: False. If you define

a variable ssn_text = redact(user.ssn), and the ssn_text variable

is already defined by the time docassemble gets around to

assembling a document with the redact option set to False, then

your “unredacted” document will contain a redacted Social Security

number.

Functions related to actions

Normally, when docassemble figures out what question to ask,

it simply evaluates the interview logic: it goes through the YAML

from top to bottom, and runs anything marked as initial or

mandatory (skipping over mandatory blocks that have already

been processed), and if it encounters an undefined variable, it seeks

a definition of that undefined variable by running blocks that offer

definitions of those variables.

Sometimes, however, you may want to direct docassemble to perform a specific task other than evaluating the current state of the interview logic. The mechanism for doing that is called the “actions” mechanism.

An “action” is similar to a function call in computer programming.

When you call a function, you might call cancel_application() or

submit_application(user, details). Running cancel_application()

just runs a function called cancel_application. Running

submit_application(user, details) runs a function called

submit_application, and passes user and details to the function;

these are referred to as the “arguments” of the function.

Here is some made-up code that illustrates how traditional functions work:

def cancel_application():

central_authority = CentralAuth(hostname='central-authority.example.com')

payload = {'type': 'cancel'}

send(payload, central_authority)

def submit_application(user, details):

central_authority = CentralAuth(hostname='central-authority.example.com')

payload = {'type': 'submit', 'user': user, 'details': details}

send(payload, central_authority)In docassemble, an “action” consists of an action name and an

optional dictionary of arguments. When you call the action

cancel_application, docassemble will seek out a block in your

YAML that offers to define cancel_application, and will run that

block. To locate this block, it uses the same process that it uses

when it seeks a block that defines an undefined variable.

Here is how you would implement the functions above as “actions” in your interview YAML:

event: cancel_application

code: |

send({'type': 'cancel'}, CentralAuth(hostname='central-authority.example.com'))

---

event: submit_application

code: |

send({'type': 'submit', 'user': action_argument('user'), 'details': action_argument('details')}, CentralAuth(hostname='central-authority.example.com'))Writing event: cancel_application means “this block advertises that

it defines cancel_application. You may have seen event used

before in a context like this:

mandatory: True

code: |

intro_screen

favorite_fruit

final_screen

---

event: final_screen

question: Thank you for answering my questions today.

subquestion: |

I like ${ favorite_fruit } as well.When a variable name is referenced, its definition will be sought if

the variable is undefined, but if the variable is defined, it will

continue running the Python code. The final_screen question is

different, though, because it is a dead end; final_screen is a

variable name that will never actually get defined.

Likewise, a code block with event: cancel_application will not

actually define the variable cancel_application, but it will be

executed if docassemble seeks the variable cancel_application.

“Actions” are used in a variety of contexts in docassemble,

including the url_action() function, review screens, action

buttons, editable tables, the force_ask() function, the

url_action() JavaScript function, the action_perform()

JavaScript function, the action_call() JavaScript function, the

run_action_in_session() function, the POST method of

/api/session/action.

Regardless of how actions are called, they are always processed by the

process_action() function. The next section explains how actions

work when called with the url_action() function.

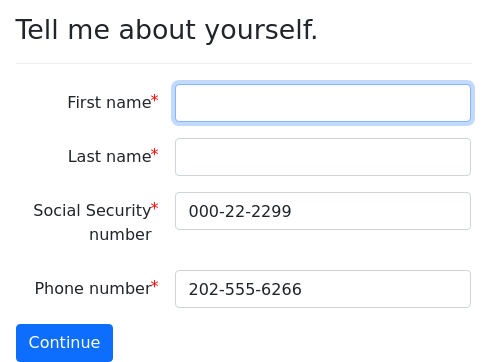

url_action() and process_action()

The url_action() function allows users to interact with

docassemble using hyperlinks embedded in questions.

url_action() returns a URL that, when clicked, will perform an

“action” within docassemble, such as running some code or asking a

question. Typically the URL will be part of a Markdown link inside

of a question, in a note within a set of fields, or it might be

the URL of an action_button_html().

The process_action() function processes “actions.” The

process_action() function is typically called for you,

behind-the-scenes, right before the interview logic is

evaluated. (However, you can call it explicitly if you want to control

exactly when (and if) it is called, and it is important to do so under

certain circumstances.)

Here is an example of using “action” URLs in an interview:

field: lucky_information_confirmed

question: |

Please confirm the following information.

subquestion: |

Your lucky number is ${ lucky_number }.

[Increase](${ url_action('set_number_event', increment=1) })

[Decrease](${ url_action('set_number_event', increment=-1) })

Also, your lucky color is ${ lucky_color }.

[Edit](${ url_action('lucky_color') })

---

event: set_number_event

code: |

lucky_number += action_argument('increment')

---

code: |

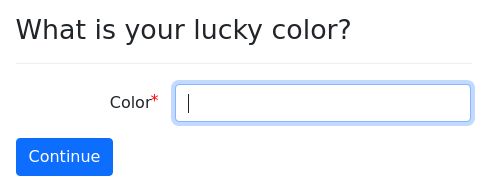

lucky_number = 2When the user clicks on the “Edit” link generated by

url_action('lucky_color'), the interview will load as normal, much

as if the user reloaded the screen. However, before initial and

mandatory blocks are processed, docassemble runs the function

process_action(). The process_action() function checks to see if

any “actions” have been requested. If no actions have been requested,

process_action() returns without doing anything. In this case,

process_action() will see that the 'lucky_color' action has been

requested. As a result, the process_action() function will look for

a question or code block that defines

lucky_color. (Internally, it calls force_ask().) Since there is

a question in the interview that offers to define lucky_color,

that question will be asked.

If the user refreshes the screen when the “What is your lucky color?”

question is showing, the user will arrive at the “What is your lucky

color?” question again. Docassemble remembers that the 'lucky_color'

action was pending, and the process_action() function will continue

sending the user to the “What is your lucky color?” question until the

user answers it. It does this even though the interview logic (the

mandatory block) does not require a definition of lucky_color. The

“action” is a diversion from the interview logic. When the user

answers the “What is your lucky color?” question, the action is

satisfied, and is no longer considered pending. process_action()

returns without forcing a question to be asked, the normal interview

logic is evaluated, and the “Please confirm the following information”

question is shown.

Even if the variable lucky_color is already defined, the

'lucky_color' action will always cause the “What is your lucky

color?” question to be shown. This makes “actions” useful for

allowing users to revisit questions they may have already answered.

When the user clicks on the link generated by

url_action('set_number_event', increment=1), the process_action()

function will look for a question or code block that defines

set_number_event. It will find the code block that was labeled

with event: set_number_event. (See Setting Variables for more

information about events.) It will then run that code block. The

Python code within that block uses action_argument() to retrieve

the value of increment that had been specified in as a parameter to

the url_action() function call.

By default, the process_action() function runs right before

docassemble starts processing your initial and mandatory

blocks. However, if you have a code block in your YAML that calls

process_action(), docassemble will refrain from running

process_action() prior to processing your initial and

mandatory blocks, and will instead rely on your interview logic to

call process_action(). A common reason to do this is when you have a

multi-lingual interview and you have an initial block that calls

set_language(); process_action() would otherwise run before the

language was initialized, and as a result questions might appear in

the wrong language.

mandatory: True

code: |

multi_user = True

---

question: |

Language/Idioma/Langue

field: user_local.language

choices:

- English: en

- Español: es

- Français: fr

---

initial: True

code: |

set_language(user_local.language)

process_action()Note that an initial block is just like a mandatory block

except that it always runs, even if it has already run to completion

in the interview session before. In this example, the mandatory

block runs first, and because it runs to completion, it will not run

again. The initial block will run every time the screen loads. This

is a multi-user interview, and the operative language will be set to

whatever language the current user speaks. (See user_local for

more information about that special object.)

Calling process_action() manually in an initial block can also be

useful for security purposes. You might want to ensure that actions

can only be carried out if the user is logged in:

initial: True

code: |

if user_logged_in():

process_action()You can pass as many named parameters as you like to an “action.” For example:

question: Hello

subquestion: |

You can set lots of information by

[clicking this link](${ url_action('set_stuff', fish='trout', berry='strawberry', money=65433, actor='Will Smith')}).

---

event: set_stuff

code: |

info = action_arguments()

user_favorite_fish = info['fish']

user_favorite_fruit = info['berry']

if info['money'] > 300000:

user_is_rich = True

actor_to_hire = info['actor']In this example, we use action_arguments() to retrieve all of the

arguments to url_action() as a Python dictionary.

You can think of “actions” as temporary diversions from the regular interview logic. When the action is over, the regular interview logic resumes. When the action is considered to be over depends on what the action refers to.

- If the action refers to a variable defined by a

question, the action will be over when the user answers thequestion. Thequestionwill be asked even if the variable is already defined. - If the action refers to the

eventname of aquestionblock, the action will be over when the user clicks acontinuebutton on thequestion. If thequestiondoes not have acontinuebutton, thequestionwill be a dead end and the action will never be over. - If the action refers to the

eventname of acodeblock, docassemble will run thecodeand it will consider the action to be over no matter what thecodeblock does. From within such acodeblock, you can callforce_ask()to cause additional actions to run. - If the action refers to a variable defined by a

codeblock, the code will be run in a more “persistent” manner thancodedesignated as anevent. If thecodestops running, for example because an undefined variable is encountered and aquestionneeds to be asked, theprocess_action()function will continue to run the action the next time the screen loads. When thecoderuns through to completion, docassemble will continue looking backward through the YAML for other blocks that offer to define the variable, and if it finds any, it will process those blocks according to these four rules.

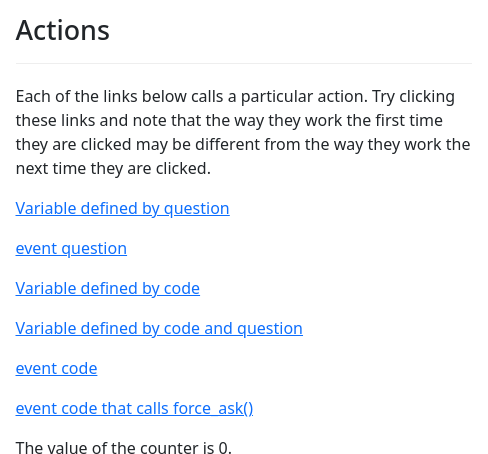

You can test out different types of actions in the following interview:

mandatory: True

question: Actions

subquestion: |

Each of the links below calls a particular action. Try clicking

these links and note that the way they work the first time they are

clicked may be different from the way they work the next time they

are clicked.

[Variable defined by question](${ url_action('favorite_fruit') })

[event question](${ url_action('fruit_info') })

[Variable defined by code](${ url_action('vegetable_asked_about') })

[Variable defined by code and question](${ url_action('legume_rationale') })

[event code](${ url_action('increment_counter') })

[event code that calls force_ask()](${ url_action('review_preferences') })

The value of the counter is ${ counter }.

---

question: |

What is your favorite fruit?

fields:

- Favorite fruit: favorite_fruit

---

event: fruit_info

question: |

Information about fruit

subquestion: |

Fruits have seeds. Some fruits are edible.

buttons:

- Continue: continue

---

code: |

vegetable_intro

favorite_vegetable

log("The favorite vegetable question has been asked.", "success")

vegetable_asked_about = True

---

question: |

Introduction to vegetables

subquestion: |

Note that the `code` block action we are in right now will not be

over unless `vegetable_intro` and `favorite_vegetable` are defined.

You can refresh the screen now and this screen will appear again.

Note that `code` blocks with `event` do not behave this way.

continue button field: vegetable_intro

---

question: |

What is your favorite vegetable?

fields:

- Favorite vegetable: favorite_vegetable

---

question: |

What is your favorite legume?

fields:

- Legume: favorite_legume

---

question: |

Why do you like ${ favorite_legume }?

subquestion: |

Note that `legume_rationale` has already been defined by a

`code` block during this action, but this `question` is

being asked anyway.

An `action` will continue past a `code` block that defines a

variable and will seek a `question` that defines the same

variable, if such a `question` exists.

fields:

- label: |

Reason liking ${ favorite_legume }

field: legume_rationale

label above field: True

input type: area

---

code: |

favorite_legume

legume_rationale = "because legumes are good"

---

event: increment_counter

code: |

counter += 1

---

code: |

counter = 0

---

event: review_preferences

code: |

force_ask('favorite_fruit', 'favorite_vegetable')Actions are “stackable.” If an action is launched while another action is still active, then when the second action is complete, the user will be returned to the first action.

You can test this out in the following interview:

mandatory: True

question: First page

subquestion: |

[Go to second page](${ url_action('second_page') })

---

question: Second page

subquestion: |

[Go to third page](${ url_action('third_page') })

continue button field: second_page

---

question: Third page

subquestion: |

[Go to fourth page](${ url_action('fourth_page') })

[Go to fourth page with forget prior](${ url_action('fourth_page', _forget_prior=True) })

continue button field: third_page

---

question: Fourth page

continue button field: fourth_pageNote that when you press a Continue button in this interview, you are taken back to where you were when you clicked on the action link; you complete the current action and “fall back” to the previous incomplete action.

The url_action() function accepts an optional keyword parameter

_forget_prior. If set to True, then when the action is run, any

actions that were already pending are “forgotten.” The above example

interview demonstrates this; note that when you click the “Go to

fourth page with forget prior” link, you go to the fourth page, but

then when you click Continue, you go back to the first page of the

interview; launching the action to go to the fourth page wipes out all

of the prior actions.

Using _forget_prior=True is useful when you have an action that

serves a navigation-related purpose. If the user clicks links to

navigate through screens, the “stacking” aspect of actions is not what

the user expects.

Note that the “current action” or the current “stack” of actions is specific to the user. In a multi-user interview, if one user has a pending action, other users will not see that pending action, even though the normal interview logic may take both users to the same screen. The action “stack” that is effective for a user is based on access credentials stored in a cookie in the browser. If a user is not logged in, these credentials are tied to the user’s session in their browser.

See interview_url_action() and scheduled tasks for information

about triggering actions externally.

action_menu_item()

One way to let the user trigger “actions” is to provide a selection in

the menu of the web app. You can do this by setting the menu_items

list. See special variables section for more information about

setting menu items.

mandatory: True

code: |

menu_items = [ action_menu_item('Review Answers', 'review_answers') ]In this example, a menu item labeled “Review Answers” is added, which when run triggers the action “review_answers.”

The action_menu_item(a, b) function returns a Python dictionary with

keys label and url, where label is set to the value of a and

url is set to the value of url_action(b).

If you want to pass arguments to the action, you can include the

arguments as keyword parameters to action_menu_item().

mandatory: True

code: |

menu_items = [ action_menu_item('Get more', 'change_count', increment=1),

action_menu_item('Get less', 'change_count', increment=-1) ]One keyword parameter has special meaning. If you set _screen_size

to 'small', then the menu item will only appear on small screens.

If you set it to 'large', it will only appear on large screens. A

“large” screen is Bootstrap md size or above.

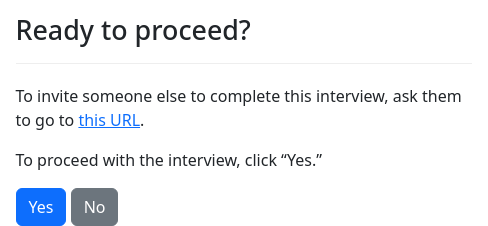

interview_url()

The interview_url() function returns a URL to the interview that

provides a direct link to the interview and the current variable

store. This is used in multi-user interviews to invite additional

users to participate.

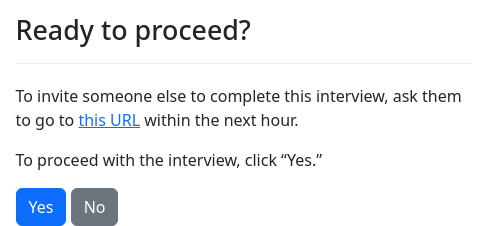

mandatory: True

code: |

multi_user = True

---

question: |

Ready to proceed?

subquestion: |

To invite someone else to complete

this interview, ask them to go to

[this URL](${ interview_url() }).

To proceed with the interview,

click "Yes."

yesno: ready_to_proceedPeople who click on the link (other than the current user) will not be

able to access the interview answers unless multi_user is set to

True. This is because interviews are encrypted on the server by

default. Setting multi_user to True disables this encryption.

Note that the communication between docassemble and the browser

will always be encrypted if the site is configured to use HTTPS.

The server-side encryption merely protects against the scenario in

which the server running docassemble is compromised.

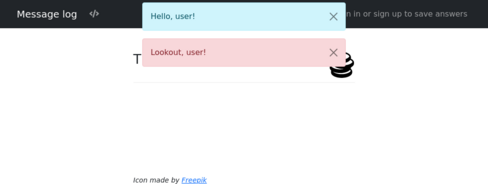

You can include keyword arguments to interview_url(). These will be