Overview of document creation methods

There are several ways to make downloadable documents using the

attachment block. Each has its own features and limitations.

Method 1: generating documents from scratch using Markdown

First, you can generate attachments from Markdown. In the same way that you format the text of questions, you can format the text of attachments. Suppose you write this in the document source:

Hello, ${ user }. This text is in **bold face**.

% if user.age_in_years() > 30:

You cannot be trusted!

% endifThis become the following in the resulting document:

Hello, John Doe. This text is in bold face.

You cannot be trusted!

In this way, you can produce documents in PDF, RTF, and DOCX format.

In addition to using Markdown, you can use docassemble-specific markup codes to do things like center text, insert a page break, or insert a case caption.

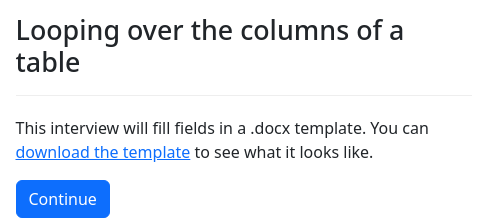

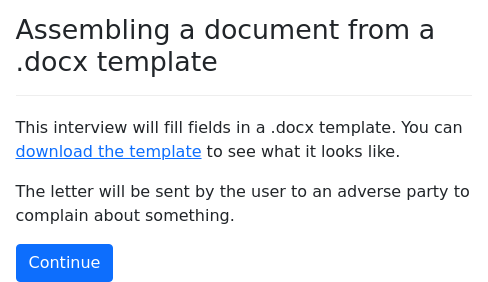

Method 2: generating documents from DOCX templates

The second method of assembling documents is to prepare a document template in DOCX format and use the Jinja2 template language to plug in variables from your interview.

For example, suppose you write this in the DOCX template file:

Hello, {{ user }}. This text is in bold face.

{%p if user.age_in_years() > 30 %}

You cannot be trusted!

{%p endif %}

The document content would look like this:

Hello, John Doe. This text is in bold face.

You cannot be trusted!

From the DOCX template, you can generate PDF or DOCX output.

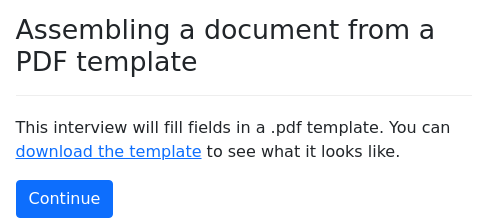

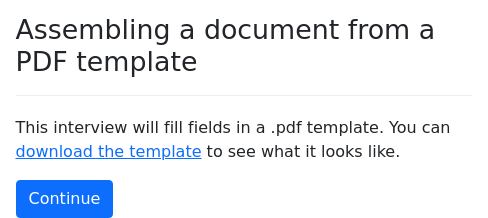

Method 3: filling in fields in a PDF

The third way to assemble documents is to generate PDF files using templates that you prepare in Adobe Acrobat Pro or

other software that can edit PDF form fields. You put the template

file in the data/templates folder of a package (or the

“Templates” folder in the Playground). The attachment block

will take the template and “fill in the blanks”

using values from interview variables, providing the user with a

filled-in version of the template.

Comparison of the methods

Each method has benefits.

The advantage of the DOCX and PDF methods is that you have more direct, WYSIWYG control over document formatting.

The advantage of the Markdown method is that you can concentrate on the content and let docassemble handle the formatting. For example, there are automatic methods for generating case captions in legal documents created from Markdown, whereas if you create your legal document in DOCX format, you will need to construct your caption in the .docx template file and make sure that it gets filled in correctly. The Markdown method allows for more flexible formatting of the if/then/else statements within paragraphs. In the .docx template method, you have to write:

I {% if employed %}have a job.{% else %}am unemployed.{% endif %}

By contrast, Markdown treats single line breaks as spaces, so you can write:

I

% if employed:

have a job.

% else

am unemployed.

% endifYou may find it easier to read your if/then/else statements when you can arrange them vertically in this fashion – particularly when you have nested if/else statements.

If you use the PDF fill-in field method to populate fields in a PDF file, you will have total control over pagination, but you will need to worry about whether the user’s content will fit into the provided fields. Also, the PDF fill-in field method requires that you write an itemized list of fields in your document and the values you want those fields to have. Markdown documents and DOCX fill-in forms are more flexible because they do not require this itemization of fields.

All three of these methods make use of the attachment specifier to

indicate how a document should be made.

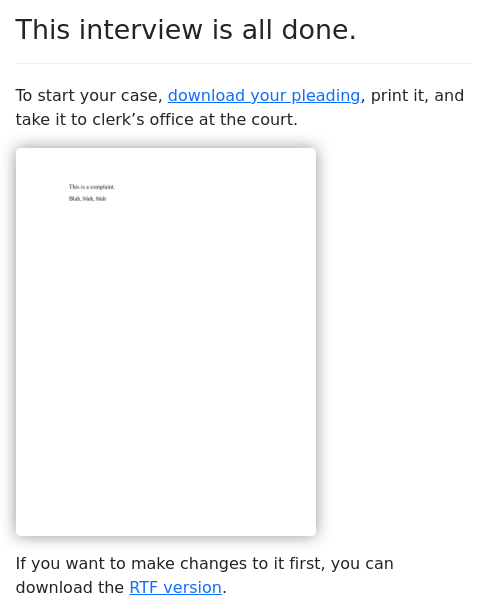

Creating files from Markdown

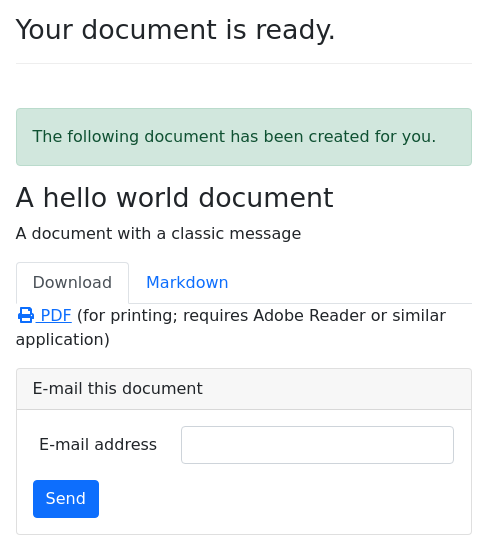

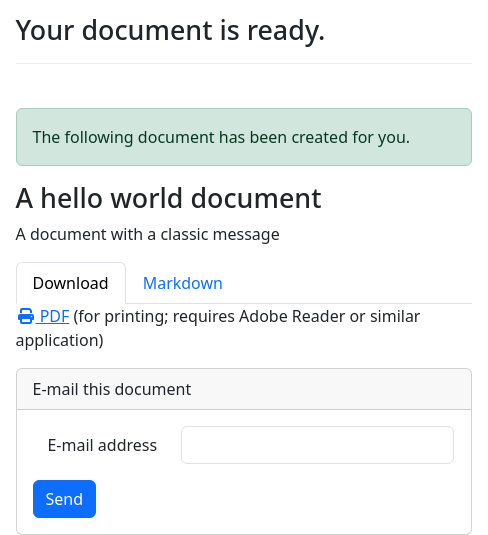

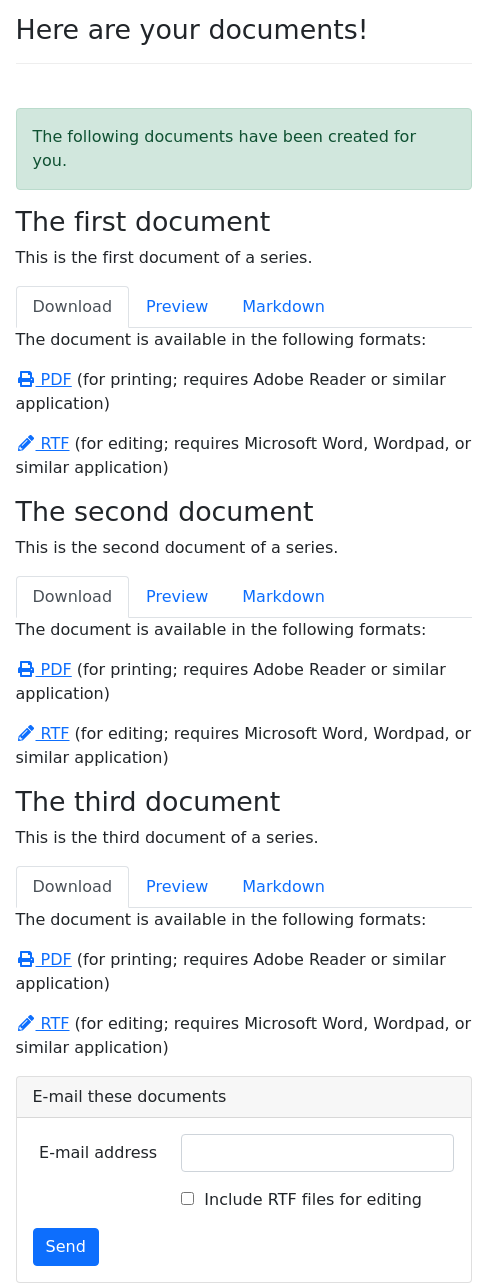

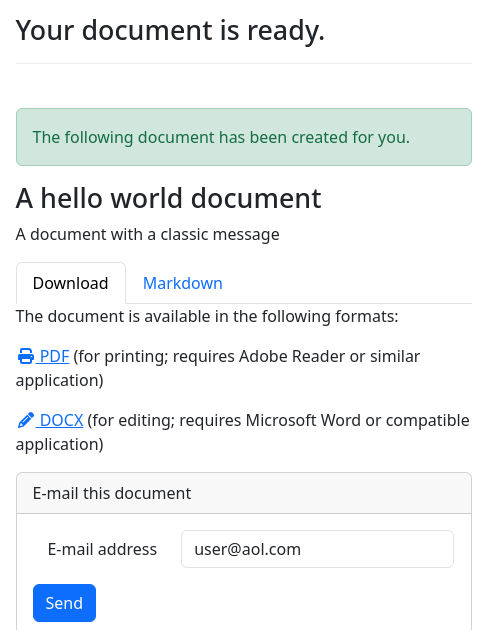

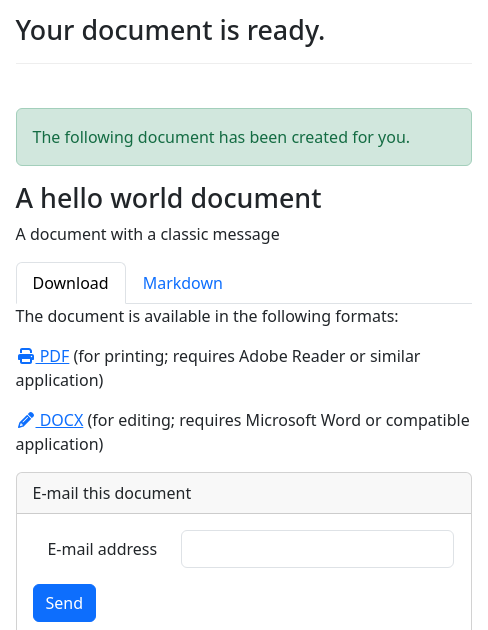

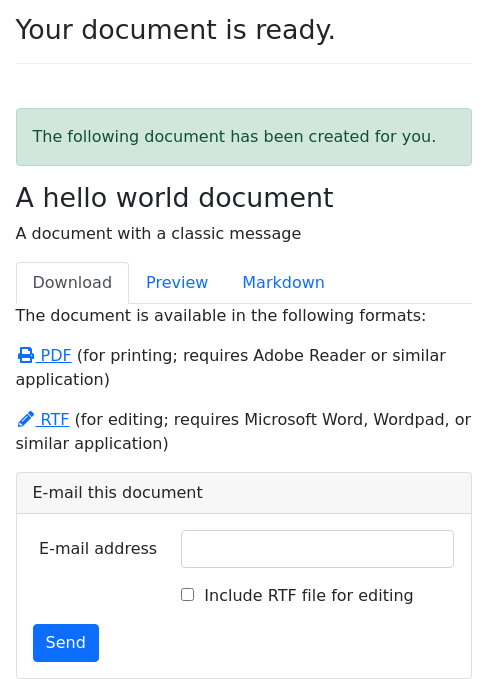

Creating PDF and RTF files from Markdown

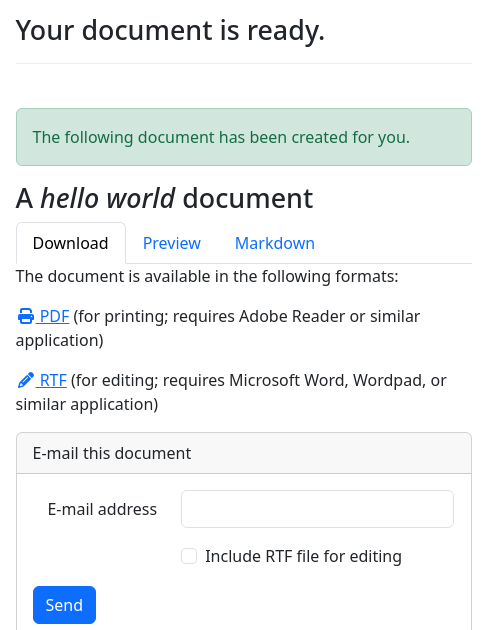

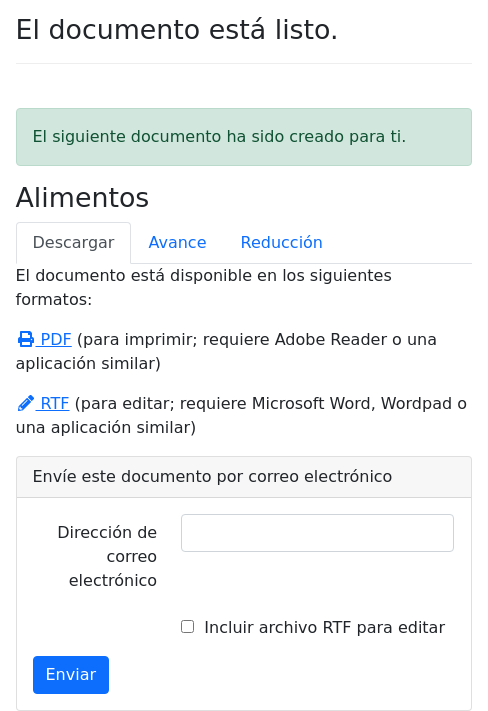

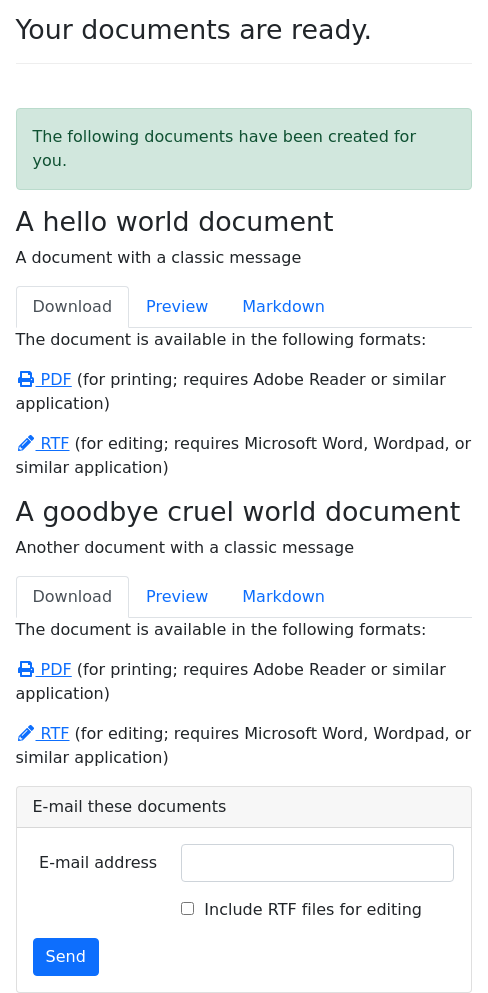

The following attachment block offers the user a PDF file and an RTF

file containing the phrase “Hello, world!”

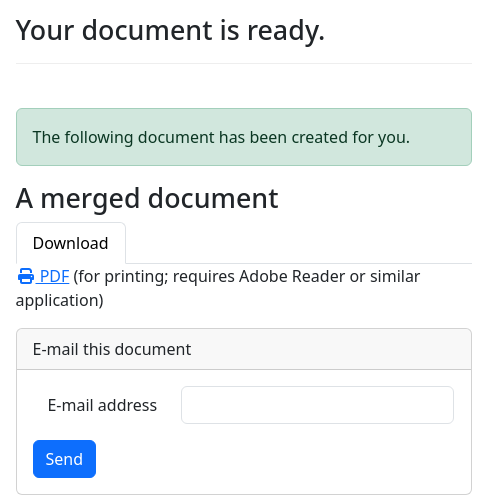

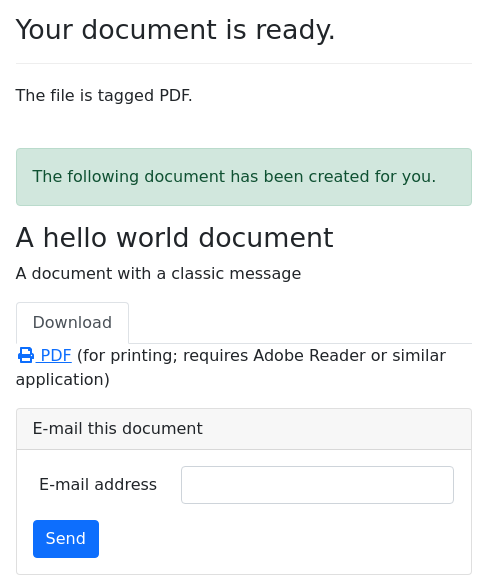

mandatory: True

question: Your document is ready.

attachment:

- name: A hello world document

filename: Hello_World

description: |

A document with a classic message

content: |

Hello, world!The content item can contain Mako and Markdown. Pandoc

converts the content into PDF, RTF, and HTML (the HTML is just for

previewing the document in the browser).

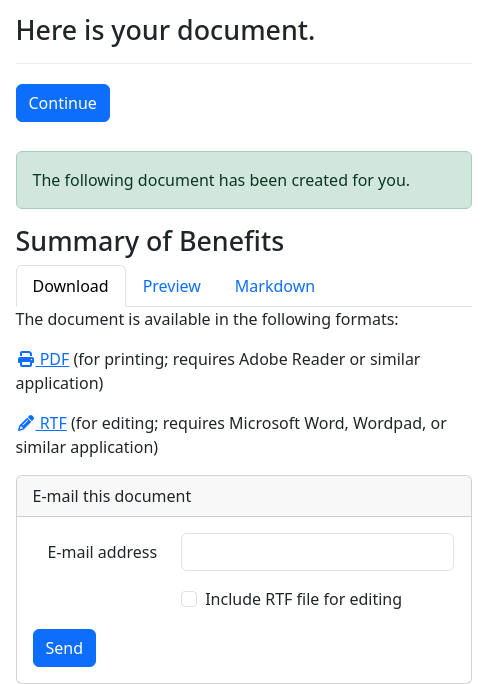

The PDF file will be called Hello_World.pdf and will look

like this in a PDF viewer (depending on the user’s software):

The RTF file will be called Hello_World.rtf and will look

like this in a word processor (depending on the user’s software):

If the user clicks the “Preview” tab, an HTML version of the document will be visible:

Creating DOCX files from Markdown

docassemble can use Pandoc to convert Markdown into a

Microsoft Word .docx file. These .docx files are not created by

default because they do not support all of the features that are

supported by RTF and PDF formats. To generate .docx

files, specify docx as one of the valid formats:

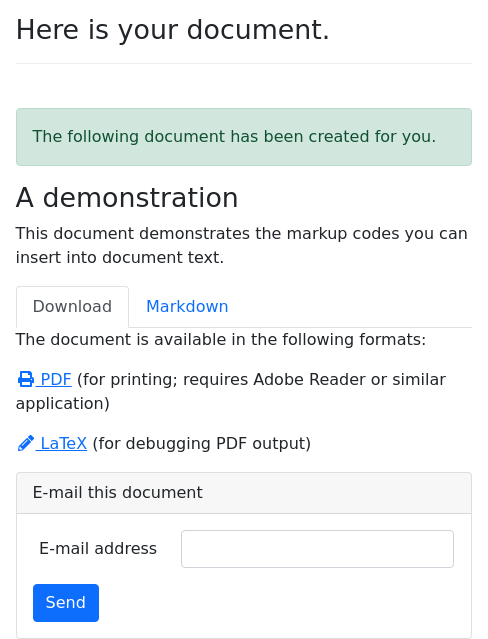

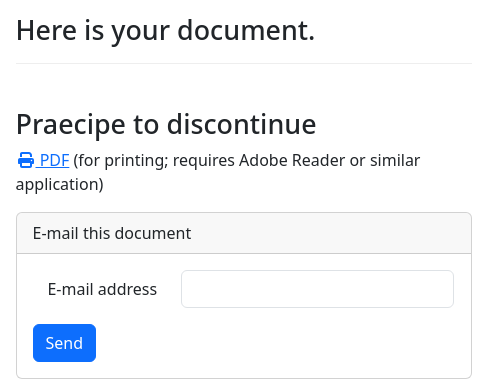

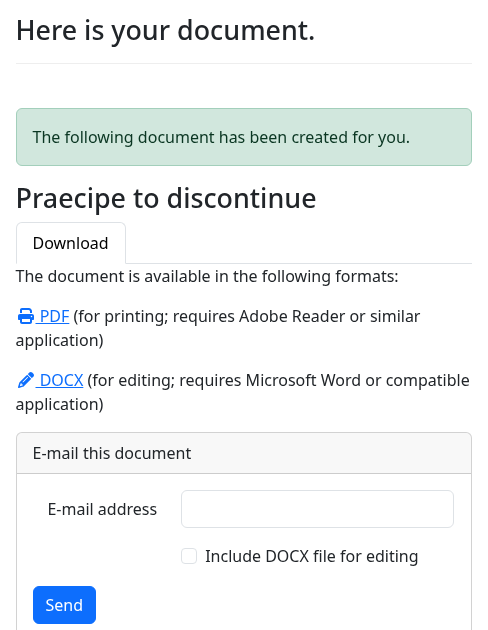

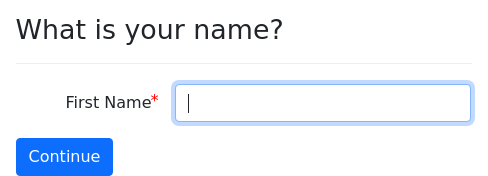

question: Here is your document.

attachments:

- name: Summary of Benefits

filename: benefits_summary

valid formats:

- docx

- pdf

content: |

[BOLDCENTER] Summary of Benefits

${ client } is entitled to

benefits plan ${ benefits }.

mandatory: TrueTo customize document styles, headers, and footers in your .docx file,

see the docx reference file setting, discussed below.

There are some formatting features that Pandoc supports when

converting to .rtf that are not available when converting to .docx, so

you might want to use .rtf conversion for that reason. However, the

.rtf format can be user-unfriendly, and in some circumstances it would

be better to have a .docx version. Luckily, LibreOffice can convert

.rtf files to .docx format. If you include rtf to docx as one of

the valid formats, docassemble will convert Markdown to RTF

format and then use LibreOffice to convert the RTF file to .docx

format. The result is that you get a .docx file instead of an .rtf

file.

question: Here is your document.

attachments:

- name: Summary of Benefits

filename: benefits_summary

valid formats:

- rtf to docx

- pdf

content: |

[BOLDCENTER] Summary of Benefits

${ client } is entitled to

benefits plan ${ benefits }.

mandatory: TrueNote that you can also assemble .docx files from templates that you

compose in Microsoft Word. See the docx template file feature,

which is described below.

Creating Markdown files from Markdown

If you want to download the assembled Markdown source, include md as

one of the valid formats:

question: Here is your document.

attachments:

- name: Summary of Benefits

filename: benefits_summary

valid formats:

- md

content: |

[BOLDCENTER] Summary of Benefits

${ client } is entitled to

benefits plan ${ benefits }.

mandatory: TrueReading Markdown content from separate files

If the content of your document is lengthy and you would rather not

type it into the interview YAML file as a content specifier within

an attachment block, you can import the content from a separate

file using content file:

question: Your document is ready.

attachment:

- name: A *hello world* document

filename: Hello_World_Document

content file: hello.md

mandatory: TrueThe content of the Markdown file, hello.md, is:

Hello, world!Files referenced with content file are assumed to reside in the

data/templates directory within the package in which the interview

YAML file is located. You can specify filenames in other locations

by specifying a package name and path. For example:

content file: docassemble.demo:data/templates/complaint.mdThe content file can also refer to a list of file names:

content file:

- introduction.md

- jurisdiction.md

- discussion.mdIn this case, the content of multiple content file files will be

concatenated.

If content file refers to a dictionary in which the only key is

code, the code will be evaluated as Python code, and the result

will be used as the file.

code: |

template_file_to_use = 'hello.md'

---

question: Your document is ready.

attachment:

- name: A *hello world* document

filename: Hello_World_Document

content file:

code: template_file_to_use

mandatory: TrueIn this example, the code evaluated to the name of a file in the

templates folder. The code may also evaluate to a URL, DAFile,

DAFileList, DAFileCollection, or DAStaticFile.

Formatting documents with special markup tags

In addition to using Markdown syntax, you can use docassemble-specific markup tags to control the appearance of documents.

[START_INDENTATION]- From now on, indent the first line of every paragraph.[STOP_INDENTATION]- From now on, do not indent the first line of every paragraph.[BEGIN_TWOCOL] First column text [BREAK] Second column text [END_TWOCOL]- Puts text into two columns.[FLUSHLEFT]- Used at the beginning of a paragraph to indicate that the paragraph should be flushed left and not indented.[FLUSHRIGHT]- Used at the beginning of a paragraph to indicate that the paragraph should be flushed right and not indented.[CENTER]- Used at the beginning of a paragraph to indicate that the paragraph should be centered.[BOLDCENTER]- Like[CENTER]except that text is bolded.[NOINDENT]- Used at the beginning of a paragraph to indicate that the first line of the paragraph should not be indented.[INDENTBY 1in]- Used at the beginning of a paragraph to indicate that all the lines of the paragraph should be indented on the left. In this example, the amount of indentation is one inch. You can express lengths using units ofinfor inches,ptfor points, orcmfor centimeters.[INDENTBY 1in 0.5in]- This is like the previous tag, except it indents both on the left and on the right. In this example, the amount of left indentation is one inch and the amount of right indentation is half an inch.[BORDER]- Used at the beginning of a paragraph to indicate that the paragraph should have a box drawn around it. (The border will only go around one paragraph; that is, the effect of[BORDER]lasts until the next empty line. You can use[NEWPAR]in place of an empty line to extend the effect of the[BORDER]tag to another paragraph.)[SINGLESPACING]- From now on, paragraphs should be single-spaced without indentation the first lines.[ONEANDAHALFSPACING]- From now on, paragraphs should be one-and-a-half-spaced, with indentation of first lines.[DOUBLESPACING]- From now on, paragraphs should be double-spaced, with indentation of first lines.[TRIPLESPACING]- From now on, paragraphs should be triple-spaced, with indentation of first lines.[TIGHTSPACING]- This is like[SINGLESPACING]except there is no spacing between paragraphs.[NBSP]- Insert a non-breaking space.[ENDASH]- Normally,--produces an en-dash, but if you want to be explicit,[ENDASH]will do the same thing.[EMDASH]- Normally,---produces an em-dash, but if you want to be explicit,[EMDASH]will do the same thing.[HYPHEN]- Insert a hyphen. Normally,-produces a hyphen, but if you want to be explicit,[HYPHEN]will do the same thing.[BLANK]- Insert___________________.[BLANKFILL]- Insert a wider version of__________________. In some output formats, this will fill the width of the area.[PAGEBREAK]- Insert a manual page break.[PAGENUM]- Insert the current page number.[SECTIONNUM]- Insert the current section number.[NEWPAR]- Insert a paragraph break. (Cannot be used within[FLUSHLEFT],[FLUSHRIGHT],[CENTER], or[BOLDCENTER]environments.)[SKIPLINE]- Skip a line (insert vertical space). This is different from[NEWPAR]because[NEWPAR]breaks a paragraph but multiple calls to[NEWPAR]will not insert additional vertical space. (Cannot be used within[FLUSHLEFT],[FLUSHRIGHT],[CENTER], or[BOLDCENTER]environments.)[BR]- Insert a line break.[BR]is useful to use with environments like[FLUSHLEFT],[FLUSHRIGHT],[CENTER], and[BOLDCENTER]that only apply to a single paragraph. Within the[BEGIN_TWOCOL]environment, a standard Markdown paragraph break (pressing enter twice, i.e., leaving one blank line) has the same effect.[TAB]- Insert a tab (horizontal space), e.g., to indent the first line of a paragraph when it otherwise would not be indented.

This interview demonstrates these features:

mandatory: True

question: Here is your document.

attachment:

name: A demonstration

filename: demo_document

description: |

This document demonstrates the

markup codes you can insert into

document text.

valid formats:

- pdf

- tex

metadata:

FirstFooterLeft: |

First of [TOTALPAGES] pages

HeaderLeft: |

Page [PAGENUM] of [TOTALPAGES]

content: |

[BOLDCENTER] Lorem Ipsum Dolor Sit

Amet

[BEGIN_CAPTION]

Consectetur adipiscing elit.

Integer nec ${ client_name } odio.

Praesent libero.

[VERTICAL_LINE]

Sed cursus ante dapibus diam.

Sed nisi.

[END_CAPTION]

[CENTER] Nulla quis sem at

nibh elementum imperdiet.

Duis sagittis ipsum. Praesent

mauris. Fusce nec tellus sed

augue semper porta. Mauris massa.

Proin ut ligula vel nunc egestas

porttitor.

Vestibulum lacinia arcu eget nulla.

Class aptent taciti sociosqu ad

litora torquent per conubia nostra,

per inceptos himenaeos.

Curabitur sodales

ligula in libero. Praesent

mauris. Fusce nec tellus sed

augue semper porta. Mauris massa.

Proin ut ligula vel nunc egestas

porttitor.

[FLUSHLEFT] Sed dignissim. [NEWLINE]

Lacinia nunc. [NEWLINE]

Curabitur tortor. [NEWLINE]

These lines are [NEWLINE]

flushed left.

Pellentesque nibh.

[NOINDENT] Primis tacimates eos

in. Vel affert vituperata te, eos

te melius legimus temporibus. At

quaeque aliquando contentiones

his. First-line indentation is

suppressed in this paragraph.

[FILE stareps.eps]

Unless a width is specified, images

will be displayed four inches wide.

Maecenas mattis. Sed convallis

tristique sem.

[FLUSHRIGHT] Proin ut ligula

vel nunc egestas porttitor.

[NEWLINE]

Quisque volutpat condimentum

velit. [NEWLINE]

We are flushed right.

Morbi lectus risus, iaculis vel,

suscipit quis, luctus non, massa.

Time for a page break.

[PAGEBREAK]

Nulla facilisi. Ut fringilla.

Suspendisse potenti.

[INDENTBY 3in] Curabitur tortor.

Pellentesque nibh. Aenean quam.

In scelerisque sem at dolor.

Maecenas mattis. Sed convallis

tristique sem. Proin ut ligula

vel nunc egestas porttitor. I

am indented by three inches.

[INDENTBY 1in 1in] Morbi lectus

risus, iaculis vel, suscipit quis,

luctus non, massa. Fusce ac

turpis quis ligula lacinia

aliquet. Sed convallis tristique

sem. I am indented by one inch

on each side.

Now, let's put text in two columns

side by side.

[BEGIN_TWOCOL]

This is the first column.

Nulla facilisi.

Let's insert some vertical space.

[SKIPLINE]

Cras metus.

[BREAK]

This is the second column.

Cras metus. Let's have some

vertical space again.

[SKIPLINE]

Integer id quam.

Morbi mi.

[END_TWOCOL]

Quisque nisl felis, venenatis

tristique, dignissim in,

ultrices sit amet, augue.

[FLUSHLEFT] [FILE bluediamond.png, 0.5in]

Maecenas mattis. Sed convallis

tristique sem.

[BORDER] Vestibulum ante ipsum

primis in faucibus orci luctus et

ultrices posuere cubilia

Curae; [FILE bluediamond.png, 10pt]

Morbi lacinia molestie dui.

Here we see various types of dashes.

Praesent[HYPHEN]mauris. Nulla

quis [ENDASH] sem at nibh

elementum imperdiet. Duis

sagittis[EMDASH]ipsum.

[BORDER] Class aptent

taciti sociosqu ad litora torquent

per conubia nostra, per inceptos

himenaeos.

[NEWPAR]

Curabitur sodales ligula in libero.

Sed dignissim lacinia nunc.

[NEWPAR]

You can include paragraph breaks

inside of a border.

Aenean quam. In scelerisque sem at

dolor. Maecenas mattis. Sed

convallis tristique sem. Let us

now stop indenting the first line

of each paragraph.

[STOP_INDENTATION]

Duis sagittis ipsum. Praesent

mauris. Fusce nec tellus sed

augue semper porta. Mauris massa.

Proin ut ligula vel nunc egestas

porttitor.

Praesent mauris. Fusce nec tellus sed

augue semper porta.

[TAB] Even though we are no longer

indenting the first line of each

paragraph automatically, we can

still indent manually.

Vestibulum lacinia arcu eget nulla.

Class aptent taciti sociosqu ad

litora torquent per conubia nostra,

per inceptos himenaeos. Let us go

back to indenting the first line

of each paragraph.

[START_INDENTATION]

Duis sagittis ipsum. Praesent mauris.

Fusce nec tellus sed augue semper

porta. Mauris massa. Proin ut

ligula vel nunc egestas porttitor.

Vestibulum lacinia arcu eget nulla.

Class aptent taciti sociosqu ad

litora torquent per conubia nostra,

per inceptos himenaeos. Let's try

single spacing now.

[SINGLESPACING]

Ullum primis scripserit ne vis, ad eam

quem dictas dissentias. Alia

scripserit vel cu, choro delicata

dissentiunt mel no, reque persequeris

mei an. Paulo graeci ex eos, no usu

dicit inimicus. In putant ornatus

forensibus cum, percipit mediocrem

in vel.

Alii timeam eos ut, habeo oblique

ocurreret ei sea. Quis utroque

definiebas et per, ad sumo

repudiandae eam, pro no sale

adolescens. Habeo splendide

evertitur has eu, in has vocent

signiferumque. Ex qui homero graeci

quaerendum, nulla veniam blandit

ei mea. Sea at idque referrentur.

Sit autem liberavisse te. Let's

go back to double spacing now.

[DOUBLESPACING]

Sea ad tacimates elaboraret,

vel simul urbanitas efficiantur id.

Id mel option denique. Ludus essent

eu ius, natum option appareat cu mea,

in saepe deterruisset pri. Mei et vero

admodum. At quas pertinax sed, et mel

modo probo iriure. Per te sententiae

elaboraret. Cum tritani delectus

definitionem ne.Formatting documents with Pandoc templates and metadata

You can also control global formatting options by setting metadata

for the document. These options are passed through to Pandoc, where

they are applied to document templates.

---

question: Your document is ready.

sets: provide_user_with_document

attachment:

- name: A *hello world* document

filename: Hello_World_Document

metadata:

SingleSpacing: True

fontsize: 10pt

description: A document with a **classic** message

content: |

Hello, world! Quisque ut tempus enim. Aliquam tristique

placerat metus sollicitudin imperdiet. Donec eget dignissim

libero, eu elementum justo.

Maecenas iaculis mollis aliquam. Nullam vestibulum erat in

sapien ultrices dignissim eu et turpis. Vivamus vestibulum felis

eu sodales ornare. Nunc auctor sapien et porttitor posuere.

---Metadata values can contain Mako template commands.

To set interview-wide default values for the metadata, you can use

attachment options.

Metadata applicable to RTF and PDF files

- If you wish to use a standard document title, set the following:

titleauthor- a listdate

toc- default is not defined. If defined, a table of contents is included.SingleSpacing- set this toTruefor single spacing and no indentation of first lines of paragraphs.OneAndAHalfSpacing- set toTruefor 1.5 spacing, with indentation of first lines.DoubleSpacing- set this toTruefor double spacing with indentation of first lines. This is the default.TripleSpacing- set this toTruefor triple spacing with indentation of first lines.fontsize- default is12pt. Must be one of10pt,11pt, and12pt.Indentation- not defined by default. InSingleSpacingmode, which by default has no indentation of the first line of each paragraph,Indentationcan be set toTrueto force the indentation of the first line of each paragraph. The amount of indentation is 0.5 inches but this can be customized withIndentationAmount. InDoubleSpacingmode, first-line indentation is enabled by default and can be turned off by settingIndentationAmountto0pt.IndentationAmount- not defined by default. When double spacing is used, the default is 0.5 inches of first-line indentation in each paragraph.- To set the text of headers and footers (which can contain Mako and

Markdown), define one or more of the following:

FirstFooterLeftFirstFooterCenterFirstFooterRightFirstHeaderLeftFirstHeaderCenterFirstHeaderRightFooterLeftFooterCenterFooterRightHeaderLeftHeaderCenterHeaderRight

Metadata applicable to generated PDFs only

The following metadata tags only apply to PDF file generation. To change analogous formatting in RTF files, you will need to create your own RTF document template (for more information on how to do that, see the next section).

HangingIndent- set this toTrueif you want text in lists to using hanging indentation.fontfamily- default isTimes New Roman, but if you installed your system before version 0.4.13, the default ismathptmx, which is a variant of Times Roman.langandmainlang- not defined by default. If defined, polyglossia (for XeTeX) or babel is loaded and the language is set tomainlangif polyglossia is loaded andlangif babel is loaded.papersize- default isletterpaper.documentclass- default isarticle.numbersections- default isTrue. If true, sections are numbered; if false, they are not. (In LaTeX,secnumdepthis set to 5, otherwise 0.)geometry- default isleft=1in,right=1in,top=1in,bottom=1in,heightrounded. These are options for the the geometry package that set the page margins.TopMargin- default is1in. If you changed the top margin ingeometry, change it here as well.BottomMargin- default is1in. If you changed the bottom margin ingeometry, change it here as well.FooterSkip- default is not defined. If defined, will set thefootskipoption of the geometry package to control spacing between the footer and the text.author-meta- default is not defined. Sets author item of PDF metadata using thepdfauthoroption of hyperref.title-meta- default is not defined. Sets title item of PDF metadata using thepdftitleoption of hyperref.citecolor- default is not defined. Sets thecitecoloroption of hyperref, which will default toblueif this is not defined.urlcolor- default is not defined. Sets theurlcoloroption of hyperref, which will default toblueif this is not defined.linkcolor- default is not defined. Sets thelinkcoloroption of hyperref, which will default tomagentaif this is not defined.abstract- default is not defined. If defined, it will include an article abstract in the standard LaTeX format.header-includes- you can set this to a list of lines that will be included in the header of the LaTeX file. You can use this if you want to load a custom package, for example.

Additional customization of document formatting

You can exercise greater control over document formatting by creating

your own template files for Pandoc. The default template files are

located in the docassemble.base package in the

docassemble/base/data/templates directory. The files include:

Legal-Template.tex- this is the LaTeX template that Pandoc uses to generate PDF files.Legal-Template.yml- default Pandoc metadata for theLegal-Template.textemplate, in YAML format. Options passed throughmetadataitems within anattachmentwill append or overwrite these default options.Legal-Template.rtf- this is the template that Pandoc uses to generate RTF files.Legal-Template.docx- this is the reference file that Pandoc uses to generate DOCX files. You can edit this file to change default styles, headers, and footers.

To use your own template files, specify them using the following

options to attachment:

initial yaml: one or more YAML files from which Pandoc metadata options should be gathered. If specified, the default fileLegal-Template.ymlis not loaded, so you can use this as a way to substitute a different set of metadata in place ofLegal-Template.ymlwhile still using the standardtemplate fileLegal-Template.tex. If specifying more than one file, use YAML list syntax.additional yaml: one or more YAML files from which Pandoc metadata options should be gathered, in addition to whatever options are loaded throughinitial_yaml. This can be used to load the metadata inLegal-Template.ymlbut to overwrite particular values. If specifying more than one file, use YAML list syntax.template file: a single.texfile to be used as the Pandoc template for converting Markdown to PDF.rtf template file: a single.rtffile to be used as the Pandoc template for converting Markdown to RTF.docx reference file: a single.docxfile to be used as the Pandoc docx reference file for converting Markdown to DOCX.

Filenames are assumed to reside in the data/templates directory

within the package in which the interview YAML file is located. You

can specify filenames in other packages by including a reference to a

package and directory. For example:

template file: docassemble.demo:data/templates/MyTemplate.texHere is an example:

---

question: Your document is ready.

sets: provide_user_with_document

attachment:

- name: Response to Motion for Summary Judgment

filename: Summary_Judgment_Response

additional yaml:

- docassemble.pennsylvania:data/templates/legal_format.yml

- docassemble.pennsylvania:data/templates/pleading_format.yml

template file: summary_judgment_template.tex

rtf template file: summary_judgment_template.rtf

content: |

The court should decide in my favor.

---If this question appears within a YAML file located in the package

docassemble.pa_family_law, the assumption is that the files

summary_judgment_template.tex and summary_judgment_template.rtf

will exist in the directory docassemble/pa_family_law/data/templates

within that package.

If you want to use a custom template for all the attachments in a given interview, you do not have to specify the same values for every attachment. Instead, you can set attachment template options that will be applied to all attachments in the interview:

---

attachment options:

additional yaml:

- docassemble.pennsylvania:data/templates/legal_format.yml

- docassemble.pennsylvania:data/templates/pleading_format.yml

template file: summary_judgment_template.tex

rtf template file: summary_judgment_template.rtf

metadata:

SingleSpacing: True

fontsize: 10pt

---If you use an interview-wide attachment options block to set

defaults, you can override those defaults for a particular attachment

by providing specific options within the question block. If you

specify metadata in both the attachment options and the

attachment block, the metadata in the attachment block will

merge with the metadata in the attachment options block.

If the interview YAML has more than one attachment options block,

the settings in later blocks will override the settings in earlier

blocks.

Assembling DOCX templates

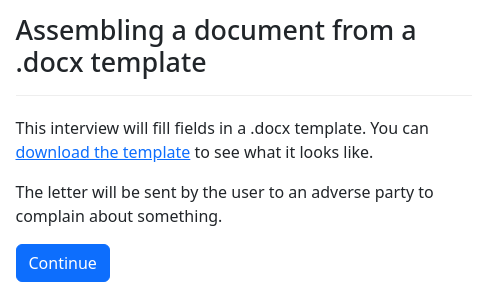

You can assemble documents from DOCX template files by referring to a

docx template file.

question: |

Here is your document.

subquestion: |

Does it meet your approval?

yesno: user_approves

attachment:

name: Your letter

filename: letter

docx template file: letter_template.docx

valid formats:

- pdf

- docxThis allows you to use Microsoft Word to design your document and

apply formatting. docassemble will simply “fill in the blanks.”

(This is in contrast to the method of

using docx as one of the valid formats, described

above. When you use that method, you assemble a document

from scratch by writing Markdown text that is then converted to

DOCX format.)

The file referenced with docx template file is assumed to reside in

the data/templates directory of your package, unless a specific

package name is specified. For example, you could refer to a DOCX

file in another package by writing:

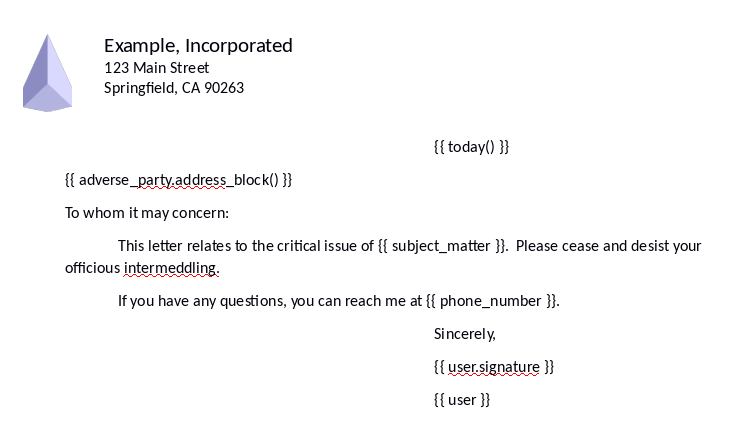

docx template file: docassemble.missouri-family-law:data/templates/form.docxIn the example above, the letter_template.docx file contains the following text:

If you give docx template file a YAML list of files, the files

will be concatenated and then assembled. (Note that some DOCX

features can be lost in the process of concatenation.)

The docx template file feature relies heavily on the Python

package known as python-docx-template. This package uses the

Jinja2 templating system to indicate fields in the DOCX file and

logic based on Python expressions. Jinja2 is different from the

Mako templating system, which docassemble primarily uses, but it

serves the same general purpose.

When you work on DOCX templates, be careful not to confuse the rules

of Mako and Jinja2. The biggest difference between the formats is

that Mako uses the syntax ${ variable_name }, while Jinja2 uses

the syntax {{ variable_name }}.

In Mako, you would write an if/else statement like this:

You may wish to distribute your property to your

% if user.child.number() > 0:

heirs.

% else:

friends.

% endifIn Jinja2, you would write:

You may wish to distribute your property to your

{% if user.child.number() > 0 %}heirs.{% else %}friends.{% endif %}Another big difference is that Jinja2 does not allow you to use

Python built-in functions like max() and any(), or built-in

Python names like None. Instead, it provides you with a variety of

filters and tests. For example, instead of writing

You have {{ len(favorite_fruits) }} favorite fruits, you

would write

You have {{ favorite_fruits | length }} favorite fruits.

Instead of writing

{% if result_of_api_call is None %}N/A{% endif %}

you would write

{% if none(result_of_api_call) %}N/A{% endif %}

Also, the python-docx-template package uses a slightly modified

version of the Jinja2 syntax to account for the fact that it is

being used inside of a DOCX file. The standard Jinja2 way of

writing a “for loop” is:

{% for item in fruit_list %}

{{ item }} is a type of fruit.

{% endfor %}In a DOCX template, however, this will result in extraneous line breaks. You can avoid this by writing:

{%p for item in fruit_list %}

{{ item }} is a type of fruit.

{%p endfor %}The p modifier indicates that the paragraph containing the {%p ... %} statement should be removed from the

document. When you edit the spacing of paragraphs in your DOCX

template file, you need to edit the paragraph spacing of paragraphs

that do not contain {%p ... %} statements.

You may need to change both the spacing after a paragraph and the

spacing before a paragraph in order to get the results you want.

Other modifiers besides p include tr for table rows, tc for

table columns, and r for “rich text.”

If you have a bulleted or numbered list in a DOCX template and you want

to display an item in the list conditionally (using an if .. endif statement),

you should use the {%p if ... %} syntax. Place

the {%p if ... %} and

the {%p endif %} statements on their own lines in the list.

If you place the {%p endif %} on the same line

as the {%p if... %} line, you may get an error about

a missing endif statement, since the p modifier could cause the

endif statement to be deleted before it is processed.

The following code in a DOCX template:

- {% if my_var == ‘A’ %}The variable is A.{% endif %}

- item2

- item3

will result in the following output if my_var is not equal to 'A':

- item2

- item3

Instead, if you write:

- {%p if my_var == ‘A’ %}

- The variable is A.

- {%p endif %}

- item2

- item3

The output will be:

- item2

- item3

The p prefix in {%p ... %} means “process the

Jinja2 in this paragraph, but don’t actually include this paragraph in

the assembled document.”

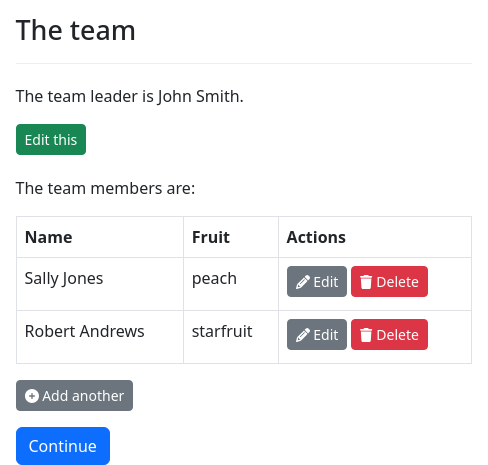

You will need to do something similar when using tables in your DOCX file. For example, when using a “for” loop over the rows of a table, you would include two extra rows:

| Name | Age |

|---|---|

| {%tr for child in children %} | |

| {{ child }} | {{ child.age_in_years() }} |

| {%tr endfor %} |

The tr prefix in {%tr ... %} means “process

the Jinja2 in this row, but don’t actually include this row in the

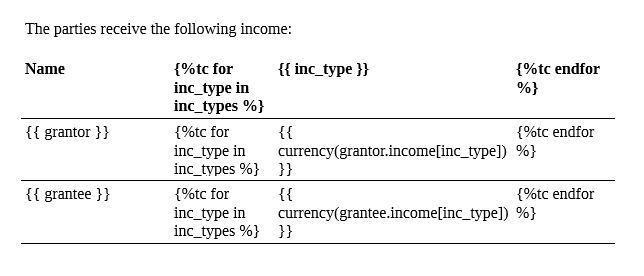

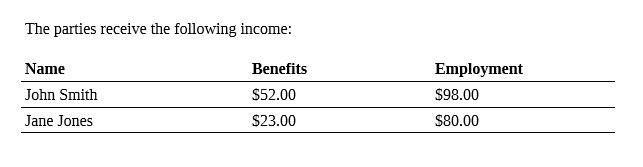

assembed document.”

When using a “for” loop over the columns of a table, you would include extra columns:

| Name | {%tc for inc_type in inc_types %} | {{ inc_type }} | {%tc endfor %} |

|---|---|---|---|

| {{ grantor }} | {%tc for inc_type in inc_types %} | {{ currency(grantor.income[inc_type]) }} | {%tc endfor %} |

| {{ grantee }} | {%tc for inc_type in inc_types %} | {{ currency(grantee.income[inc_type]) }} | {%tc endfor %} |

The tc prefix in {%tc ... %} means “process

the Jinja2 in this table cell, but don’t actually include this table

cell in the row.”

For more information about tables in DOCX files, see the subsection on tables below.

Images can be inserted into DOCX files.

This is illustrated in the example above: the variable

user.signature is a graphics image (an image of the user’s signature

created with the signature block). You can insert DAFile,

DAFileList, and DAStaticFile objects into DOCX files in a

similar way. (See include_docx_template() below for instructions

on inserting other DOCX files inside a DOCX file.) If you insert a

PDF file, it will be converted into a series of page images. If you

insert a text file, the raw text will be included. When using the

markdown filter, you can also use the [FILE ...] markup syntax to

insert an image. Do not mix image references with other text inside

of a single field (e.g., by writing {{ "Here is my dog: " +

a_file }}. Image references need to be by themselves

inside of {{ }} brackets. To change the width

of an image, use the .show() method with a width parameter. E.g.,

{{ my_image.show(width="2in") }}

Note that the paragraph spacing of the paragraph into which you insert an image may affect the appearance of the image. For example, if the line spacing of the paragraph is fixed, the image that you insert will be cropped if it is taller than the line spacing. To prevent the image from being cropped, select a flexible line spacing like “single” or “double.”

When you insert text into a DOCX file using {{ }} brackets, any newlines in the text you are inserting will be

treated as spaces, and any Markdown formatting codes will be passed

through literally. If you want your newlines and Markdown

formatting codes to translate into DOCX formatting, see the section

below on inserting multi-line or formatted text into a single field

in a DOCX file.

When you use docx template file, the user is provided with both a

PDF file and a DOCX file. The PDF file is generated by converting

the DOCX file to PDF format using LibreOffice. To suppress the

creation of the PDF version, you can add a valid formats

specifier.

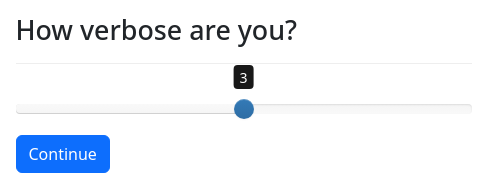

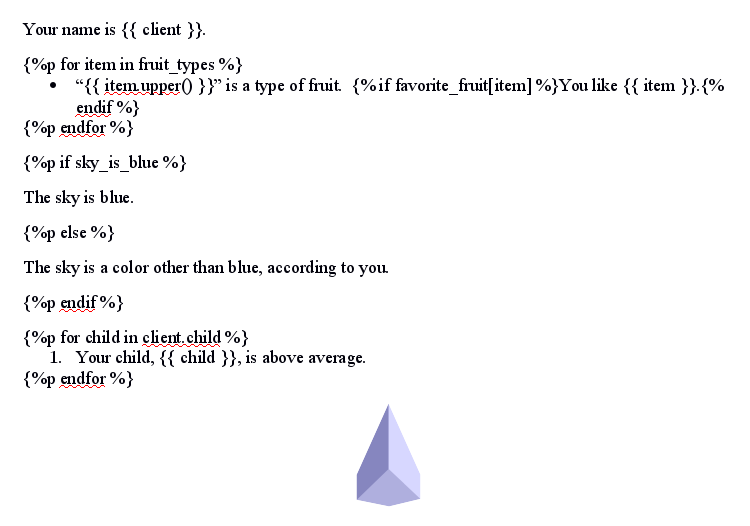

Here is an example that demonstrates how to use DAList and DADict in a DOCX template and using Jinja2 templating code.

event: document_shown

question: |

Here is the document.

attachment:

docx template file: docx-jinja2-demo.docxThe docx-jinja2-demo.docx file looks like this:

For more information on using Jinja2 in DOCX templates, see the

documentation of python-docx-template.

The section below on using code to find a template file explains how

you can use code to determine what template file to use with docx

template file.

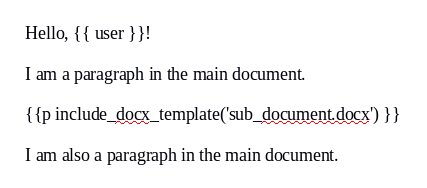

Inserting other DOCX files into DOCX templates

You can include the paragraphs of a DOCX file inside of your DOCX template.

See the documentation for the include_docx_template() function for

more information. Note that it is important to use the p form of

Jinja2 markup, by itself on a line in the document:

{{p include_docx_template(‘sub_document.docx’) }}

If you have a DOCX file in the form of a DAFile or DAFileList

object, then you can do:

{{p include_docx_template(the_file) }}

or just

{{p the_file }}

Inserting tables into DOCX templates

You can assemble tables in a DOCX template using a Jinja2 “for loop.”

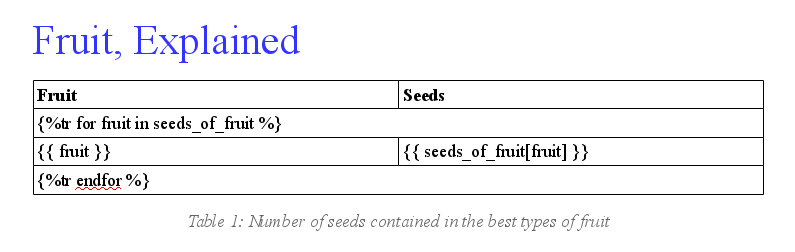

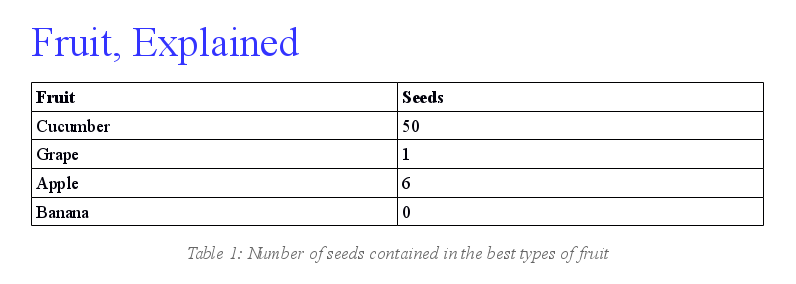

Here is an example. The DOCX template looks like this:

Note that the row that should be repeated is sandwiched between two

rows containing for and endfor Jinja2 statements. Both of these

statements use the tr prefix. These two rows, which span the width

of the table, will not appear in the final output. The final output

will look something like this:

In this example, each row corresponds to an item in a Python dict

called seeds_of_fruit. Here is an example of an interview that

gathers items into a DADict called seeds_of_fruit and provides

the DOCX file.

objects:

seeds_of_fruit: DADict

---

mandatory: true

code: |

seeds_of_fruit.there_are_any = True

introduction_shown

---

question: |

Tell me about a fruit.

fields:

- Name: seeds_of_fruit.new_item_name

- Seeds: seeds_of_fruit.new_item_value

datatype: integer

min: 0

---

question: |

Are there any other fruits you would

like to describe?

yesno: seeds_of_fruit.there_is_another

---

mandatory: True

question: |

Here is your document.

attachment:

docx template file: table_template.docxFor more information about gathering items into a DADict object,

see the Dictionary subsection of the Groups section of the

documentation.

Your DOCX tables can also loop over the columns of a table.

The following interview, which uses the template docx-table-columns.docx, illustrates this.

generic object: Individual

question: |

How much does ${ x } receive from ${ i }?

fields:

- Income: x.income[i]

datatype: currencyPassing values for particular fields

By default, all of the variables in your interview will be available

in the DOCX template. If your DOCX template uses different variable

names than are present in your interview, you can use the fields or

field code specifiers to indicate a mapping between variable names

in the DOCX template and the values that you want to be filled in.

This operates much like the PDF fill-in fields

feature. If a variable in the DOCX file is not explicitly

defined in the fields or field code list, definitions will be

sought in the interview answers.

The content of fields is converted into a data structure, which is

passed to the render() method of python-docx-template. The data

structure needs to be a Python dict, but it can contain other data

types. For example, in this interview, fields contains a list of

ingredients:

mandatory: True

question: |

Here is your recipe. Enjoy!

attachment:

name: Your recipe

filename: recipe

docx template file: recipe_template.docx

fields:

- title: Mandelbrot cookies

- oven_temperature: ${ oven_degrees } degrees

- ingredients:

- apple sauce

- ${ special_ingredient }

- flour

- sugar

- preparation_time: 48 hoursIn your DOCX file, you will need to use appropriate Jinja2 syntax in order to process the list of ingredients. Here is an example of a DOCX file that uses the above data structure:

Turning off automatic conversion of DOCX variables

Normally, all values that you transfer to a DOCX template using

fields, field variables, and field code are converted so that

they display appropriately in your DOCX file. For example, if the

value is a DAFile graphics image, it will be converted so that it

displays in the DOCX file as an image. Or, if the value contains

document markup codes that indicate line breaks, these will display

as actual line breaks in the DOCX file, rather than as codes like

[BR].

However, if your DOCX file uses Jinja2 templating to do complicated things like for loops, this conversion might cause problems.

For example, suppose you have a variable vegetable_list that is

defined as a DAList with items ['potatoes', 'beets'], and you

pass it to a DOCX template as follows.

event: document_shown

question: |

Here are your instructions.

attachment:

docx template file: instruction_template.docx

field variables:

- vegetable_listThis will work as intended if your template uses vegetable_list in a

context like:

make sure to bring {{ vegetable_list }} to the partyThis will result in:

make sure to bring potatoes and beets to the party

When the DAList is converted, the .comma_and_list() method is

automatically applied to make the data structure “presentable.”

However, suppose you wanted to write:

{%p for vegetable in vegetable_list: %}

Don't forget to bring {{ vegetable }}!

{%p endfor %}In this case, since the variable vegetable_list has been converted

into a literal piece of text, potatoes and beets, the for loop

will loop over each character, not over each vegetable. You will get:

Don’t forget to bring p!

Don’t forget to bring o!

Don’t forget to bring t!

Don’t forget to bring a!

Don’t forget to bring t!

and so on.

You can prevent the conversion of vegetable_list into text by using raw

field variables instead of field variables. For example:

event: document_shown

question: |

Here are your instructions.

attachment:

docx template file: instruction_template.docx

raw field variables:

- vegetable_listNow, the vegetable_list variable in the DOCX template will be a

real list that Jinja2 can process. The output will be what you expected:

Don’t forget to bring potatoes! Don’t forget to bring beets!

The conversion to text is also done if you use field code or code

to pass variables to a DOCX template. In order to pass variables in

“raw” form using field code or code, you can wrap the code in the

raw() function. For more information, see the

documentation for the raw() function.

Inserting multi-line or formatted text into a single field in a DOCX file

If you insert text into a docx template file using {{

the_variable }}, and the the text you are inserting

contains newlines, the newlines will show up as spaces in the DOCX

file. Also, if the text contains Markdown formatting, it will be

inserted into the DOCX file literally.

If the text that you want to insert contains newlines, and you want

the newlines to be reflected in the DOCX file as manual line breaks,

write {{ the_variable | manual_line_breaks }}

instead.

If the text that you want to insert contains Markdown formatting,

and you want that formatting to be translated into DOCX formatting,

insert it using markdown Jinja2 filter or the inline_markdown

Jinja2 filter.

If some_variable contains Markdown formatting that includes

paragraph breaks, lists, or other paragraph-level formatting, write:

{{p some_variable | markdown }}

If some_variable contains Markdown indicating bold, italics, or

other character-level formatting, but no paragraph breaks, lists, or

other paragraph-level formatting, write:

I went to {{r some_variable | inline_markdown }} for lunch.

It is important that you understand the difference between character-level content and paragraph-level content. You see this distinction in Microsoft Word when you use “Styles.” Some Styles are character-level or “inline” because they only affect things like bold, italics, underline, and color. Other Styles are paragraph-level because they affect things like paragraph indentation, bullets, or numbering. A paragraph break is a paragraph-level concept, whereas a manual line break is a character-level concept.

Under the rules of python-docx-template, you need to use the

prefix {{r when the contents contain

character-level DOCX formatting (which is what the inline_markdown

filter produces), and you need to use {{p when

the contents return paragraph-level DOCX formatting (which is what the

markdown filter and the the insert_docx_template() function

produce). It is very important that you get this right, because the

symptoms of a mistake are confusing: the contents may simply

disappear, or the DOCX file may get corrupted because you are

inserting bad XML.

When using the markdown filter to insert multiple paragraphs into a

DOCX file, note that according to the Markdown standard, a single

newline does not break a paragraph; you need two newlines to break a

paragraph. If you want to convert single newlines into paragraphs

breaks, there is another Jinja2 filter that can help. Instead of

writing

{{p the_text | markdown }}, write

{{p the_text | paragraphs | markdown }}.

The paragraphs filter runs the text through the

single_to_double_newlines() function.

If you insert Markdown hyperlinks into the DOCX file, it is important that you prepare your DOCX template file so that it can use hyperlinks properly. To do this, use Word or LibreOffice to edit your DOCX template, type some text, highlight the text, and convert the text into a hyperlink. You can then delete the hyperlink. This will have a side effect on the DOCX file that will prepare it to accept hyperlinks. See character style of hyperlinks in DOCX files for more information about how hyperlinks appear in DOCX files. If you do not do this, hyperlinks will not work properly in documents converted from DOCX to PDF.

Since 2020, there have been changes to the way the markdown filter

works. If you installed docassemble before these changes went into

effect, you will not see these changes unless you update your

Configuration. The changes were implemented in this way so as not to

break backwards-compatibility.

The following Configuration directives enable the modern (superior) functionality:

new markdown to docx: True

new template markdown behavior: TrueIf you created your Configuration (i.e. did docker run for the first

time) since version 1.3.29, your configuration will already contain

these directives.

If you created your Configuration before 1.3.29, you should edit your Configuration so that it contains these lines, and then you will have the modern functionality. Keep in mind, though, that you may need to edit your existing templates if they rely on the legacy behavior.

One legacy behavior was that the markdown filter was applied

automatically to any template inserted into a docx template

file. You could get around this by inserting the template with

my_template.show_as_markdown(), which would not apply the

filter. The new template markdown behavior: True Configuration

directive, which is available as of version 1.3.29, enables better

functionality, which is not to apply the markdown filter

automatically. If my_template is a template, you need to insert

it using {{p my_template | markdown }} or {{r my_template | inline_markdown }}, depending

on whether the template should be treated as paragraph-level or inline.

Another legacy behavior is that the markdown filter only worked with

character-level Markdown formatting, and had to be included in DOCX

files using {{r some_variable | markdown }}.

The new markdown to docx: True Configuration directive, which is

available as of version 1.1.2, enables better functionality, which is

that the markdown filter inserts paragraph-level DOCX formatting,

and is used with the p prefix ({{p some_variable |

markdown }}) while the inline_markdown filter inserts

inline DOCX formatting, and is used with the r prefix ({{r

some_variable | inline_markdown }}).

Another way to insert formatted text using Jinja2 is to use the

“rich text” feature of python-docx-template. The RichText

Jinja2 filter allows you to include line breaks inside of variable

text:

The swift brown {{r animal | RichText }} jumped over the lazy dog.

Using this filter, any newline (\n) in animal will be converted

into a manual line break and any \a character will be converted into

a paragraph break. When using RichText, you must always use the r

prefix, {{r ... }}.

Jinja2 filters

Jinja2 does not allow you to write every kind Python expression, the

way that Mako does; there are limitations, such as not being able to

refer to certain built-in names like None. Jinja2 allows you to

do sophisticated things, however, but it encourages the use of

“filters” rather than the writing of Python code. There are a

number of built-in filters in Jinja2 that you can use. In

addition, there are some docassemble-specific filters, which are

either discussed above or are the names of functions.

RichTextadd_separatorsalphaallanycapitalizechaincomma_and_listcomma_listcountry_namecurrencyfix_punctuationinline_markdownmanual_line_breaksmarkdownnice_numberordinal_numberordinalparagraphsphone_number_formattedphone_number_in_e164redactromansalutationsingle_paragraphtitle_caseverbatimword

You can also write your own

filters. To do so, you need to write a module file. For example, here

is a module file that creates a filter called no_ssn for removing

Social Security Numbers.

# pre-load

import re

from docassemble.base.util import register_jinja_filter

def remove_ssn(text):

return re.sub(r'[0-9][0-9][0-9]-[0-9][0-9]-[0-9][0-9][0-9][0-9]', 'XXX-XX-XXXX', text)

register_jinja_filter('no_ssn', remove_ssn)For this to work, the module file has to be installed on the server or present in the Modules folder of a user’s Playground.

The register_jinja_filter() function is similar to

update_language_function() in that it needs to run when the server

starts and the server loads modules. That is why the line #

pre-load is at the top. Also note that register_jinja_filter is

not exported when you do from docassemble.base.util import *.

If you have a filter that you want to apply to all Jinja2 variable

interpolations, see auto jinja filter.

Inserting blocks of text more than once in a document

Jinja2 supports the use of “macros,” which are like Python commands except that instead of running Python code, they insert content into the document.

Here is an example of a document in which a paragraph following a

particular template needs to be inserted multiple times. The docx

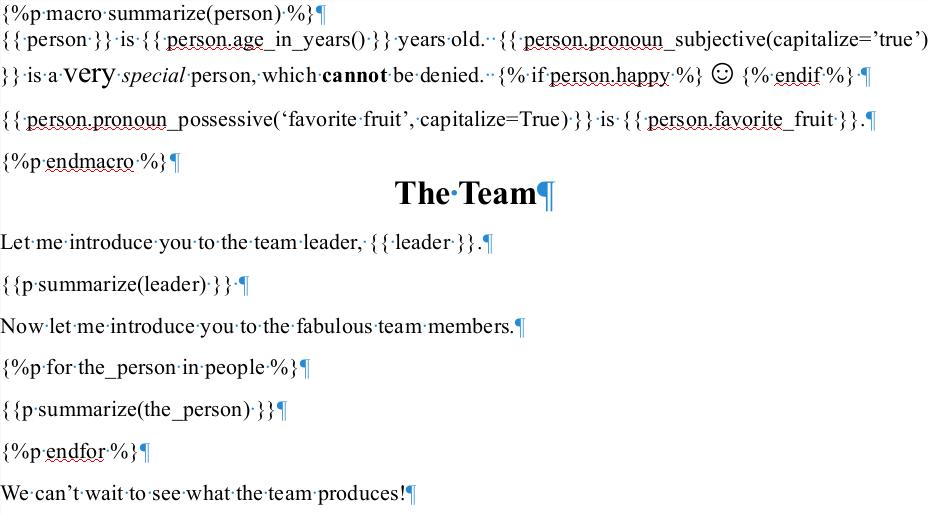

template file is a file called team.docx, which contains the

following content:

Note the use of {%p macro ... %} and

{%p endmacro ... %}.

The macro in this document contains two paragraphs with Jinja2 statements. The DOCX formatting defined in the macro will be reproduced wherever the macro is inserted.

Here is an interview that assembles a document from team.docx:

event: final_screen

question: |

Here is a description of the team.

attachment:

name: Team

filename: team_summary

docx template file: team.docxYou can also define a macro that includes character-level text.

{% macro say_hello(friend) %}Hello, {{ friend }}!{% endmacro %}

Then you can use the macro by calling it inside brackets:

{{ say_hello(plaintiff) }} How are you today?

The difference from the previous example is that the p prefix is not

used.

When you need to insert text programmatically into different parts of

a DOCX document, using a macro in Jinja2 is generally preferable

to inserting a template or Markdown-formatted text. It is a

good general practice to use the DOCX file to control anything

relating to document formatting. Keep in mind that Markdown was not

designed for typesetting; it was designed for indicating the general

meaning of parts of text in a form-independent manner.

Using tables of contents and other references in DOCX files

If you are using docx template file and your template file uses a

table of contents or other page references that will change depending

on how the document is assembled, set update references to True.

mandatory: True

question: Here is your document

attachment:

name: Brief

filename: brief

update references: True

docx template file: doc-with-toc.docxThis will cause LibreOffice to update all of the references in the document before saving it and converting it to PDF.

You can also set update references to a Python expression. If the

expression evaluates to a True value, the references will be updated.

If update references is not specified, the default behavior is not

to update the references.

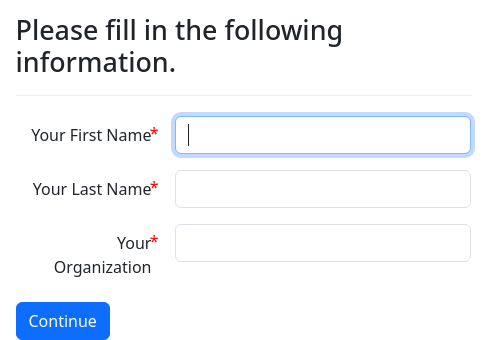

Filling PDF templates

If you have a PDF file that contains fillable fields (e.g. fields

added using Adobe Acrobat Pro or a similar application),

docassemble can fill in the fields of the PDF file using

information from an interview and provide the user with a copy of that

PDF file with the fields filled in. To do this, use the

attachment specifier as above, but instead of providing content

or content file, provide a pdf template file and a dictionary of

fields.

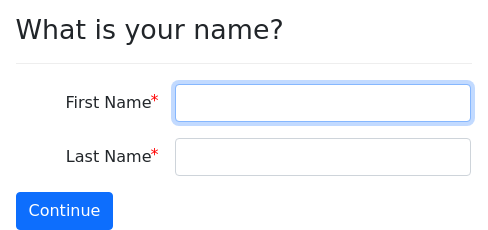

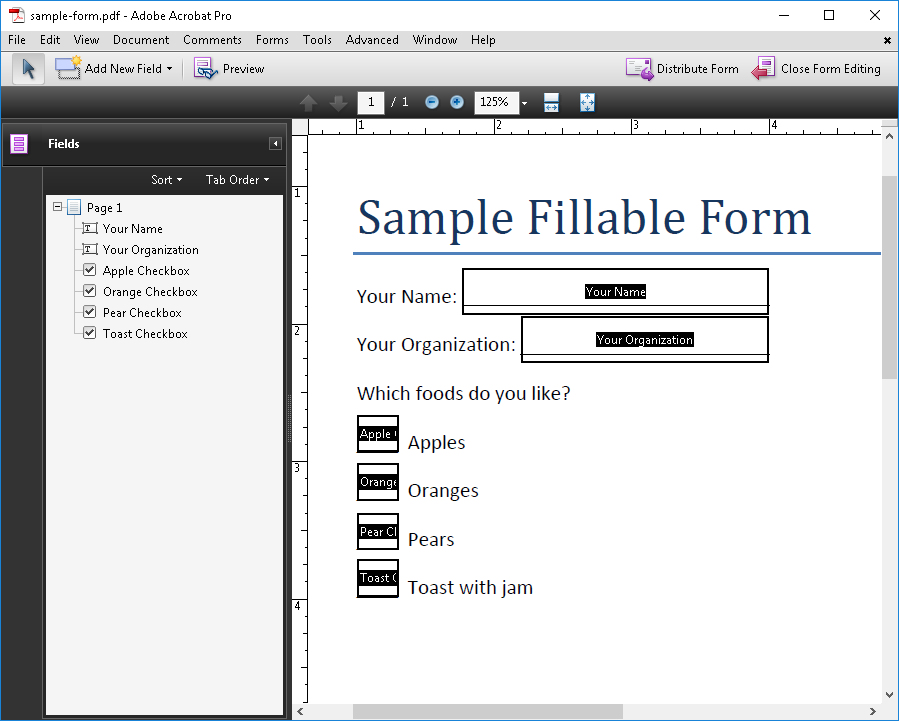

For example, here is an interview that populates fields in a file called sample-form.pdf:

question: |

Here is your PDF form

attachment:

name: A filled-in form

filename: filled-form

pdf template file: sample-form.pdf

fields:

- Your Name: |

${ user }

- Your Organization: |

${ user.organization }

- Apple Checkbox: |

${ likes_apples }

- Orange Checkbox: |

${ likes_oranges }

- Pear Checkbox: |

${ likes_pears }

- Toast Checkbox: |

${ likes_toast }

mandatory: TrueThe pdf template file is assumed to reside in the data/templates

directory of your package, unless a specific package name is

specified. For example, you could refer to a file in another package

by writing:

pdf template file: docassemble.missouri-family-law:data/templates/form.pdfIn Adobe Acrobat Pro’s “Add or Edit Fields” mode, the PDF file looks like this:

The fields must be in the form of a YAML list of dictionaries, or

a single dictionary. The names of the fields listed in fields must

correspond exactly with the names of the fields in the PDF file.

Luckiliy, there is a tool that will help you extract the literal

field names from a PDF file.

If your PDF document has many fields, it is strongly recommended that

you use Adobe Acrobat Pro to give each field a concise, meaningful,

and accurate field name (as well as a helpful tooltip). Adobe

Acrobat Pro has a feature for automatically assigning names to

fields, but this tool often assigns incorrect names. You should go

through this process before you generate the attachment

specifier for filling fields in the PDF file.

While it is legal for a PDF file to contain more than one field with the same name, please note that docassemble is unable to populate such fields. You must give each field in your PDF file a unique name.

When writing the values of the fields, you can use Mako, but not Markdown. If you use Markdown, it will be interpreted literally.

The section below on passing values using code explains alternative ways that you can populate the values of fields in a PDF file.

You have a choice whether to list fields as a single dictionary or a list of dictionary items. Providing the fields in the form of a list is usually preferable because it provides an order in which the fields should be evaluated; if you only provide a single dictionary, the items will be evaluated in a random order.

The section below on using code to find a template file explains how

you can use code to determine what template file to use with pdf

template file.

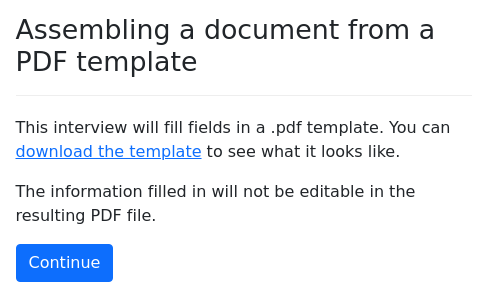

Making PDF files non-editable

By default, the PDF files created by filling in

forms in a pdf template file can be edited by the user; the fill-in

form boxes will still exist in the resulting document.

If you want to prevent users from editing the forms created through

pdf template file, set the editable specifier to False (or a

Python expression that evaluates to False). For example:

question: |

Here is your PDF form

attachment:

name: A filled-in form

filename: filled-form

pdf template file: sample-form.pdf

editable: False

fields:

Your Name: |

${ user }

Your Organization: |

${ user.organization }

Apple Checkbox: |

${ likes_apples }

Orange Checkbox: |

${ likes_oranges }

Pear Checkbox: |

${ likes_pears }

Toast Checkbox: |

${ likes_toast }

mandatory: TrueUsing pdftk to fill the fields

By default, docassemble uses pikepdf to fill in fields. If you

want docassemble to use pdftk to fill in the fields, use pdftk:

True.

question: |

Here is your PDF form

attachment:

name: A filled-in form

filename: filled-form

pdf template file: sample-form.pdf

pdftk: True

fields:

Your Name: |

${ user }

Your Organization: |

${ user.organization }

Apple Checkbox: |

${ likes_apples }

Orange Checkbox: |

${ likes_oranges }

Pear Checkbox: |

${ likes_pears }

Toast Checkbox: |

${ likes_toast }If pdftk is not specified, the default behavior is determined by the

interview’s pdftk features setting. If there is no such feature,

the default is not to use pdftk.

Although pdftk is slower than pikepdf, it can render more accurate appearance streams.

Changing the font used when rendering fields as text

If you use editable: false or pdf/a: True, form fields will be

rendered to text in the PDF file. pdftk performs this task using the

Arial font to render the text. You can indicate that a different font

should be used instead:

question: |

Here is your PDF form

attachment:

name: A filled-in form

filename: filled-form

pdf template file: sample-form.pdf

editable: False

rendering font: "/usr/share/fonts/truetype/noto/NotoSans-Regular.ttf"

fields:

Your Name: |

${ user }

Your Organization: |

${ user.organization }

Apple Checkbox: |

${ likes_apples }

Orange Checkbox: |

${ likes_oranges }

Pear Checkbox: |

${ likes_pears }

Toast Checkbox: |

${ likes_toast }For best results, set rendering font to the path of a font on the

server. If you set rendering font to the name of a font, it will

work, but pdftk will use 100% CPU for several seconds as it searches

the fonts on the system, trying to retrieve the filename of the font.

To see a list of font files available on the server, you can use the font list tool.

When specifying a rendering font, you can use Mako templating.

How to insert signatures or other images into fillable PDF files

To add a signature or other image to a fillable PDF file, use Adobe Acrobat Pro to insert a “Digital Signature” into the document where you want the signature to appear. Give it the height and width you want the image to have. Give the field a unique name.

Then, the image will be a field, just like a checkbox or a text box is

a fill-in field. In your pdf template file, set the field to ${

user.signature } or another reference to an image. docassemble

will trim whitespace from the edges of the image and fit the image

into the “Digital Signature” box.

For example, here is an interview that populates text fields and inserts a signature into the template Transfer-of-Ownership.pdf:

question: |

Please sign your name below.

signature: user.signature

under: |

${ user }

---

sets: final_screen

question: Congratulations!

subquestion: |

You have now transferred everything

you own to ${ friend }.

attachment:

- name: Transfer of Ownership

filename: Transfer-of-Ownership

pdf template file: |

Transfer-of-Ownership.pdf

fields:

- "grantor": ${ user }

- "grantee": ${ friend }

- "collection": ${ prized_collection }

- "signature": ${ user.signature }It is important that each “Digital Signature” field have a unique name. If there is more than one field in the PDF template with the same name, docassemble will not be able to locate it. If you want to insert the same signature in more than one spot in a document, you can do so as long as each “Digital Signature” field has a different name. For example:

fields:

- first signature: ${ user.signature }

- second signature: ${ user.signature }

- third signature: ${ user.signature }Passing values using code

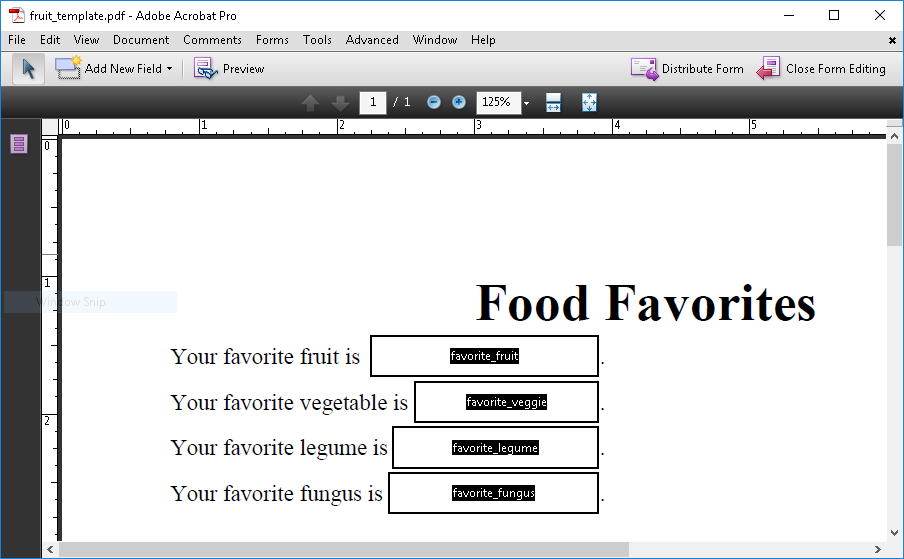

When you use the fields specifier with pdf template file, you

have to use Mako in order to pass the values of interview variables

to the template. For example, suppose you have a PDF file with these

fields:

You can use an interview like this to populate the fields:

mandatory: True

question: Here is your document.

attachment:

pdf template file: fruit_template.pdf

fields:

- favorite_fruit: ${ favorite_fruit }

- favorite_veggie: ${ favorite_veggie }

- favorite_legume: ${ favorite_legume }

- favorite_fungus: ${ favorite_fungus }However, this is a bit punctuation-heavy and repetitive. As an

alternative, you can use the field variables specifier to list the

variables you want to pass:

mandatory: True

question: Here is your document.

attachment:

pdf template file: fruit_template.pdf

field variables:

- favorite_fruit

- favorite_veggie

- favorite_legume

- favorite_fungusThis will have the same effect.

The field variables specifier only works when your variable in the

template has the same name as the variable in your interview, and when

you do not need to perform any transformations on the variable before

passing it to the template.

The field variables specifier, and other specifiers described in

this subsection, work both with pdf template file and

docx template file. But note that since the

.docx assembly process by default accesses all

of your interview variables, you will normally only need to use field

variables with PDF templates.

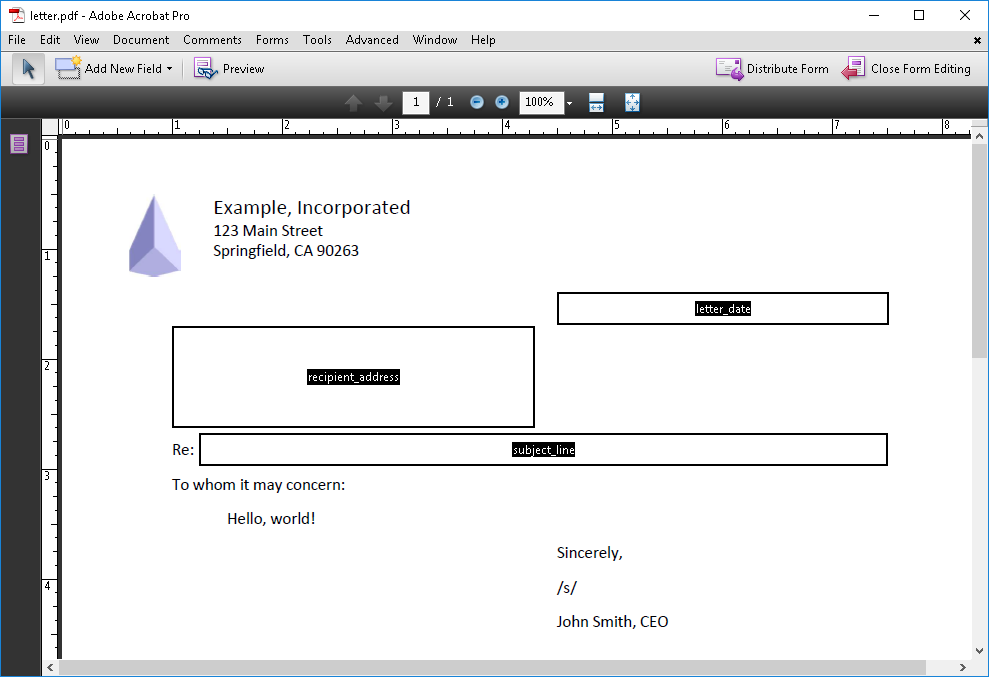

Suppose you want to pass the results of functions or methods to a template that looks like this:

One way to pass the results of functions or methods it is to use

fields, where every value is a Mako variable reference containing

code:

mandatory: True

question: Here is your document.

attachment:

pdf template file: letter.pdf

fields:

- letter_date: ${ today() }

- subject_line: ${ subject_of_letter }

- recipient_address: ${ recipient.address_block() }You can achieve the same result with less punctuation by using the

field code specifier:

mandatory: True

question: Here is your document.

attachment:

pdf template file: letter.pdf

field code:

- letter_date: today()

- subject_line: subject_of_letter

- recipient_address: recipient.address_block()There is still another way of passing values to a template: you can

include a code specifier that contains Python code that evaluates

to a Python dict in which the keys are the names of variables in the

template, and the values are the values you want those variables to

have. For example:

mandatory: True

question: Here is your document.

attachment:

pdf template file: letter.pdf

code: |

{'letter_date': today(),

'subject_line': subject_of_letter,

'recipient_address': recipient.address_block()}Note that the code must be a single Python expression, not a list

of statements. It can be difficult to cram a lot of logic into a

Python expression, so you may want to create a variable to hold the

values. For example:

mandatory: True

question: Here is your document.

attachment:

pdf template file: letter.pdf

code: letter_variables

---

code: |

letter_variables = {}

letter_variables['letter_date'] = today()

if letter_type == 'threat':

letter_variables['subject_line'] = "Litigation hold"

else:

letter_variables['subject_line'] = "Matter we discussed"

letter_variables['recipient_address'] = recipient.address_block()

reconsider: TrueNote that the use of the reconsider modifier is important here.

Remember that docassemble will only ask a question or run code

when it encounters an undefined variable. If the recipient’s address

is undefined when docassemble tries to run the code above,

docassemble will ask a question to gather it, but once that

question is answered, docassemble will have no reason to run the

above code again because letter_variables will already be defined –

albeit in an incomplete state, with a letter_date item and a

subject_line item but without a recipient_address item. Setting

reconsider to True ensures that whenever a screen in the interview

needs to know the value of letter_variables, that value will be

“reconsidered”—treated as undefined—and the code above will be

re-run in order to obtain a fresh definition of letter_variables.

The fields, field variables, and field code specifiers are not

mutually exclusive. When they are used together, they supplement each

other. (In DOCX templates, however, the fields do not supplement the

values of variables in the interview dictionary; if you use fields,

field variables, and field code, docassemble will not use the

interview dictionary as a whole.)

Here is a variation on the original PDF fill-in example above that uses code to supplement the values of fields:

question: |

Here is your PDF form

attachments:

- name: A filled-in form

filename: filled-form

pdf template file: sample-form.pdf

fields:

Your Name: |

${ user }

Your Organization: |

${ user.organization }

Apple Checkbox: |

${ likes_apples }

Pear Checkbox: |

${ likes_pears }

code: |

{"Orange Checkbox": likes_oranges,

"Toast Checkbox": likes_toast}

mandatory: TrueLike the Mako tag ${ ... }, the fields, field variables, and

field code specifiers will convert the values of your variables to a

format suitable for printing. If you are using the DOCX template

format and you only use the {{ ... }} syntax in

your template, this will always be appropriate. But if you want to

use “for loops” and other features of Jinja2 when passing variables

using fields, field variables, or field code, you should read

the next section, which explains how to pass variables in “raw” format

to the template.

When using field code, code, or

field variables to define your fields, there is a shortcut for

formatting decimal numbers: set the option decimal places to the

number of decimal places you want to use.

---

attachment:

name: My Document

filename: my_document

pdf template file: letter_template.pdf

variable name: the_document

decimal places: 2

---By default, when decimal places is not used, numbers are converted

to text using the standard Python method, which uses at least one

decimal place.

Note that decimal places does nothing for variables passed to your

template with a method other than field code, code, or field

variables. In other cases, you will need to manually format your

numbers, for example by writing something like ${ '%.3f' %

ounces_of_gold }.

If you want to assemble a document with

pdf template file or docx template file and produce a file even if

some of the variables needed for the fields are undefined, set skip

undefined to True. If skip undefined is true, then blanks will

be substituted for any fields for which a value cannot be determined

due to a variable being undefined. You can also set skip undefined

to a Python expression that evaluates to a true or false value.

If your template contains computations, using skip undefined: True

may lead to bugs that are difficult to track down, since variables

that should have certain data types will be Undefined and you will

get strange error messages.

The skip undefined setting should only be used if the document does

not need to be robust. For example, it could be used to show the user

an intermediate draft of a PDF document. It should not be used as a

crutch for allowing users to generate documents even though there are

bugs in the interview logic. Whether a variable happens to be defined

at the time a document is produced is not a good rationale for

omitting information from a document. The real question is whether

the substantive logic requires it to be defined; if the variable

should be defined, its definition should be obtained. The default

behavior of skip undefined: False imposes rigor to your interview

logic, ensuring that errors will surface.

In general, you should never rely upon defined-ness to control

anything important. Especially when your users can edit their answers

with review screens, a variable may be defined but may be

inapplicable because of another variable. For example, if you ask “Do

you want to include your cell phone number?” and then you ask “What is

your cell phone number,” the user’s cell phone number will be defined.

If the user then changes the answer to the “Do you want to include

your cell phone number?” question, then you will have a situation

where the user’s cell phone number is defined but it should not be

used. If you relied on skip undefined: True to omit the user’s cell

phone from the document, this would only work in situations when the

user did not change their mind. If the user initially said “no” to

the “Do you want to include your cell phone number?” question but then

later changed their mind and changed the answer to “yes,” then skip

undefined: True might result in the cell phone number not being

included in the document even though it should be included.

Defined-ness is an unreliable indicator of whether information is

relevant. Your logic should always be based on substantive facts, not

defined-ness.

How to get a list of field names in a PDF file

When logged in to your server as a developer, you can go to

“Utilities” from the menu and, under “Get list of fields from PDF/DOCX

template,” you can upload a PDF or DOCX file that has fillable fields in it. docassemble

will scan the file, identify its fields, and present you with the

YAML text of a question that uses that file as a pdf template

file or a docx template file with a list of fields.

The following example output is from the sample-form.pdf template referenced earlier:

---

question: Here is your document.

event: some_event

attachment:

- name: sample-form

filename: sample-form

pdf template file: sample-form.pdf

fields:

- "Your Name": something

- "Your Organization": something

- "Apple Checkbox": No

- "Orange Checkbox": No

- "Pear Checkbox": No

- "Toast Checkbox": No

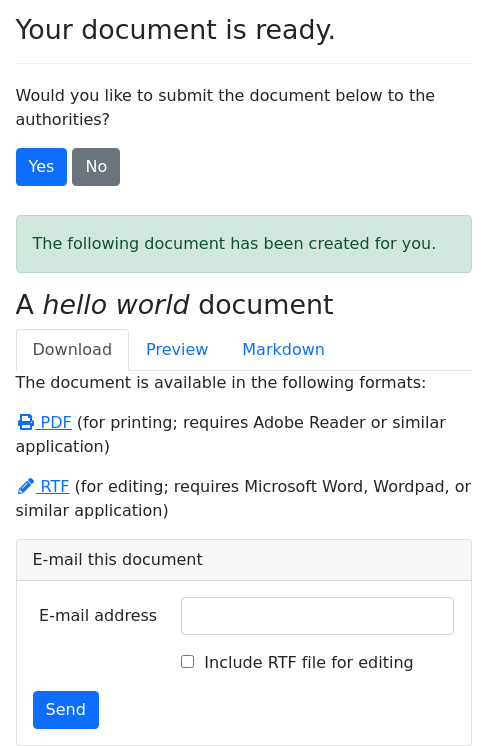

---The attachment specifier

The attachment specifier (which can also be written attachments)

creates documents that users can download and/or e-mail.

It can be used within a question or outside of a question (standalone).

mandatory: True

question: Your document is ready.

attachment:

- name: A hello world document

filename: Hello_World

description: |

A document with a classic message

content: |

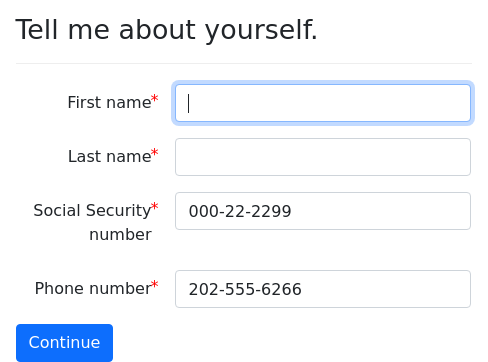

Hello, world!The name, filename, and description items can contain Mako

templates. The name and description filenames can also contain

Markdown. (The filename cannot contain Markdown, since it’s a

filename, after all.)

Saving documents as variables

Including an attachment section in a question block will offer

the user a chance to download an assembled document and e-mail it to

themselves.

Sometimes, you might want to do other things with the document, like e-mail it somewhere (behind the scenes), or post it to a web site.

You can save an assembled document to a variable by adding

a variable name key to an attachment. For example:

mandatory: True

question: Ok, all done.

subquestion: |

% if submit_to_authority:

% if sent_ok:

Your document was sent.

% else:

For some reason, I was not able to

send your document.

% endif

% else:

Ok, I will not send your document to

The Man.

% endif

---

question: Your document is ready.

subquestion: |

Would you like to submit the document

below to the authorities?

yesno: submit_to_authority

attachment:

- name: A *hello world* document

filename: Hello_World_Document

variable name: hello_file

content: |

Hello, world!

---

code: |

sent_ok = send_email(to=[authority],

template=my_email,

attachments=[hello_file])You can also assemble a document and save it to a variable without

presenting it to the user. You do not need to use attachment

with a question; it can stand on its own, and it will be evaluated

when docassemble needs the definition of the variable indicated by

a variable name within the attachment block.

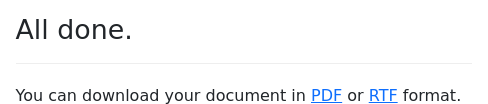

The following example creates a PDF file and an RTF file containing the message “Hello, world!” and offers the files as hyperlinks.

attachment:

filename: Hello_World

variable name: my_file

content: |

Hello, world!

---

mandatory: True

question: |

All done.

subquestion: |

You can download your document in

[PDF](${ my_file.pdf.url_for() })

or

[RTF](${ my_file.rtf.url_for() })

format.The variable indicated by variable name will be defined as an object

of class DAFileCollection. An object of this type will have

attributes for each file type generated, where each atttribute is an

object of type DAFile. In the above example, the variable

my_file.pdf will be the PDF DAFile, and the variable

my_file.rtf will be the RTF DAFile. A DAFile has the

following attributes:

filename: the path to the file on the filesystemmimetype: the MIME type of the fileextension: the file extension (e.g.,pdforrtf)number: the internal integer number used by docassemble to keep track of documents stored in the system

See objects for an explanation of the DAFile and

DAFileCollection classes.

Limiting availability of file formats

You limit the file formats that are generated by attachment.

question: Your document is ready.

attachment:

- name: A hello world document

filename: Hello_World_Document

valid formats:

- pdf

description: |

A document with a classic message

content: |

Hello, world!

mandatory: TrueIn this example, the user will not have the option of seeing an HTML preview and will only be able to download the PDF file.

Note that when you use docx template file, the user is normally

provided with both a PDF file and a DOCX file. The PDF file is

generated by converting the DOCX file to PDF format. To hide the PDF

file, set valid formats to docx only.

If you want to limit the file formats dynamically, you can specify

code under valid formats.

question: Your document is ready.

attachment:

- name: A hello world document

filename: Hello_World_Document

valid formats:

code: |

['pdf'] + (['rtf'] if user_has_privilege('admin') else [])

description: |

A document with a classic message

content: |

Hello, world!

mandatory: TrueUsing code to find a template file

Typically, when you refer to a filename in an attachment block

using pdf template file or docx template file, you refer to a file

in the data/templates directory of a package, or the “Templates”

folder of the Playground.

Alternatively, you can refer to files using code.

question: |

Please upload the template file.